Introduction

This chapter will examine Ford’s directing apprenticeship at Universal, and how some of the thematic and visual motifs associated with the director’s later work – as defined by Wollen, Eyman and Duncan, along with the themes and visual motifs I have identified through my own research – were forged over the four years he worked for the studio. Ford’s collaboration with Harry Carey underpins most of the work produced at Universal, as the actor and one-time close friend helped to create the template for the solipsistic outsider who became the primary Fordian protagonist. As will be shown, it is through this working relationship that themes such as the outsider as man of action evolved. In fact a close look at Ford’s partnership with Carey provides the first real evidence of the director’s journey towards the evolution of a distinctive auteurist style. Their collaboration initiates the genesis of a number of underlying themes, including the antimonies of garden versus wilderness and East versus West, that would evolve (as Wollen identifies) into key stylistic components of Ford’s later work.

Also explored is the evolution of other significant themes generally associated with Ford such as family, community, ritual, and ethnicity – as well as the key opposition of civilisation versus wilderness – in relation to the autobiographical, social, cultural, and technological factors that influenced the director’s work almost from the beginning. The consideration of the influence of technology takes its cue from Edward Buscombe’s suggestion, as highlighted in the introductory chapter, that these factors should be incorporated into a discussion of cinematic authorship.

This chapter is devoted almost entirely to the Western. Luckily for Ford, who was a fan of cowboy films from the outset,[1] his work for Universal Studios was almost totally confined to this genre. As will be discussed later on, the forms he worked in for the Fox Corporation were more diverse, embracing, along with the Western, genres including military, Irish-themed and Americana pictures.

Harry Carey and Universal Studios

Ford maintained that Harry Carey ‘tutored me in the early years. I learned a great deal from [him]’ (in McBride, 2003, p.109). The director established a working relationship with Carey early on that would serve as a template for Ford’s later partnerships with actors such as Henry Fonda and John Wayne. Carey embodied the archetypal ‘good bad man’ figure that became an integral component of Ford’s work. His character, Cheyenne Harry, embraced many of the distinctive traits that can be traced in a direct lineage to other Ford protagonists as played by Fonda and Wayne and, to a lesser extent, Will Rogers.

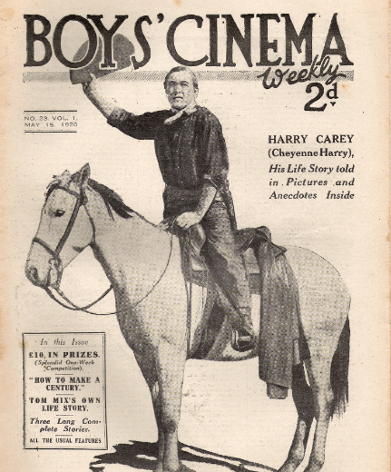

Hollywood film is by its very nature a vehicle for popular stars, so it should come as no surprise that the majority of Ford’s films for Universal featured Harry Carey who before, during, and after the period that he worked with Ford, enjoyed a certain amount of fame with the cinema-going public. I.G. Edmonds states that Carey’s character, Cheyenne Harry, was ‘Universal’s king of the cowboys until the rise of Hoot Gibson’ (Edmonds, 1977, p.95). The world-wide popularity of the Western genre ensured that actors such as Carey found fame outside of America as well. The character of Cheyenne Harry, for example, was celebrated a number of times in a series of articles

for a British publication entitled Boys’ Cinema (Fig. 5.1).

The duo’s first production was The Soul Herder in 1917, presumed lost. By the time they made their last silent film together, Desperate Trails in 1921 – another lost title – the director and actor had collaborated on twenty-five films, the majority with Carey as Cheyenne Harry. During that period, how much Ford or Carey contributed towards the creation of Carey’s cinematic persona is difficult to evaluate. Tag Gallagher maintains that Ford ‘often constructed a screen character by building on foibles or eccentricities already there in the actor. Thus, for example, Harry Carey became more Harry Carey than he actually was, i.e., more charismatic and relaxed’ (Gallagher, 1986, pp.467-468). During the years that Carey worked with Ford, his screen persona, like that of Wayne’s, evolved and matured into a more psychologically complex protagonist, suggesting that the creation of Cheyenne Harry was as much Carey’s as it was Ford’s. The actor’s son, Harry Carey Jr, is of the opinion that, at the beginning of Ford’s partnership with his father, ‘the two of them were very much alike in their creative styles [and] they loved the idea of the tramp cowboy, not the kind with the fancy clothes […]. [Cheyenne Harry] was the sort of adventurous guy who doesn’t know what’s coming up next’ (Interview with author, October 2007).

Working within the framework of the Hollywood system, one can detect in Ford’s partnership with Carey the beginnings of a proto-auteurist method of filmmaking. Although Universal had its own story department, it has been suggested by a number of Ford’s contemporaries that both he and Carey wrote many of the scenarios for their own films. According to Carey’s wife, Olive, ‘Universal would send out these terrible goddammned scripts [so] Jack and Harry would have it all in their heads. They didn’t have anything on paper. Jack would get the picture finished, [George] Hively would then write the script and send it in to the story department to keep them happy’ (Transcript of interview with Dan Ford, John Ford collection at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington).

Ford is credited with either writing the script or devising the storyline for at least ten of the films he made at Universal (Bogdanovich, 1978, pp.115-122). The fact that Ford actually participated in the development of the scenarios for some of these early films underlines his increasing creative control even at this stage, and the independence that allowed him to develop his own authorial style. Most of the films Ford made with Harry Carey, starting with The Soul Herder (1917) onwards, were shot mainly on location, thus allowing Ford the opportunity to work without interference from the studio. Ford and his crew were given almost complete autonomy regarding material, location and shooting schedule, although budget was obviously a consideration. The young director was not plagued by the presence of producers constantly looking over his shoulder during filming, which enabled him to explore an ever-increasing grasp of the language of cinema free from interruption. McBride states that, ‘as long as their Westerns turned a profit for Universal, [Ford and Carey] were left alone to play and experiment within the confines of the genre’ (McBride, 2003, p.103). The working partnership with Carey presented Ford with the opportunity to literally abandon the format of a pre-written script and apply an almost ‘guerilla’ style of shooting when making a film. It also afforded the freedom of a creative and ‘authorial’ independence and, in conjunction with Carey of course, to charge his work with themes and motifs of his own choosing.

The majority of the Carey / Ford films feature the actor playing characters separate from the main social group, who must prove their worth before acceptance by a community that represents civilisation and progress. By the time Ford came to direct Straight Shooting (1917), Carey’s recurring character, Cheyenne Harry, already personifies the concept of the ‘good bad man’ seeking redemption through acts of violence and self-sacrifice. Certain aspects of the scenario mirror the earlier William S. Hart film, Hell’s Hinges (Charles Swickard, 1916). Blaze Tracey, as played by Hart, achieves redemption by destroying a town that harbours the chief villain and his cronies, whilst Cheyenne Harry makes amends by defying the bad men who have hired him to drive a family of homesteaders off their land. At the end of Hell’s Hinges (1916) and Straight Shooting (1917), both Hart and Carey are eventually made welcome by the community they have found themselves morally obliged to protect.

This was not the way Straight Shooting (1917) ended when originally released in 1917. As Joseph McBride writes, ‘The film has come down to us with what seem like two contradictory endings – one in which Harry decides to ride away […] and another ending in which Harry tentatively decides to settle down’ (McBride, 2003, p.116). The former scenario, in which Cheyenne Harry leaves the community, is more in keeping with the nature of later Fordian characters, such as Ethan Edwards, who effectively reject domesticity and civilisation for a life in the wilderness. Upon re-release in 1925, a different ending was appended, one in which Cheyenne Harry shows intent to marry

the heroine instead (Fig. 5.2). Although the alternate ending was obviously imposed by the studio – Ford being fully employed at Fox by 1925 – it suggests that Ford’s impulse when Straight Shooting was first released in 1917, to depict Cheyenne Harry turning his back on domesticity, conflicted with studio demands for a happier resolution at the end of the film. Despite the delay in the studio changing the finale, this might perhaps be construed as an early hint that Ford’s personal style was at odds with an industrialised institution that limited the director’s freedom of expression in terms of character motivation. Ford’s later autonomy from studio constraint gave him free rein to show his characters turning away from community and civilisation – as in My Darling Clementine (1946) and The Searchers(1956) – without having to compromise his style and approach.

The protagonist as a man of action prevails almost from the inception of Ford’s directorial career. It is Cheyenne Harry in Straight Shooting (1917) who actively confronts those who endanger the family unit, whilst the more benign members of that social group stand on the sidelines, rendered helpless and impotent against those outside of the law. He defeats the corrupt cattlemen attempting to drive the settlers away, thus enabling Harry to eventually join the very community he himself was initially hired to threaten with violence.

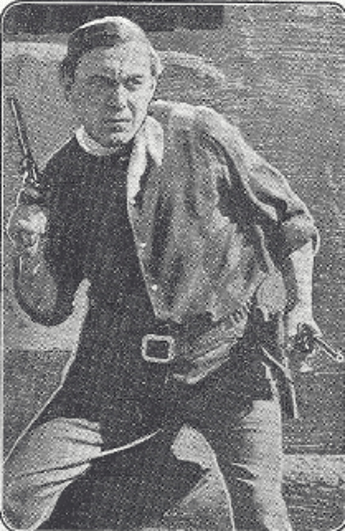

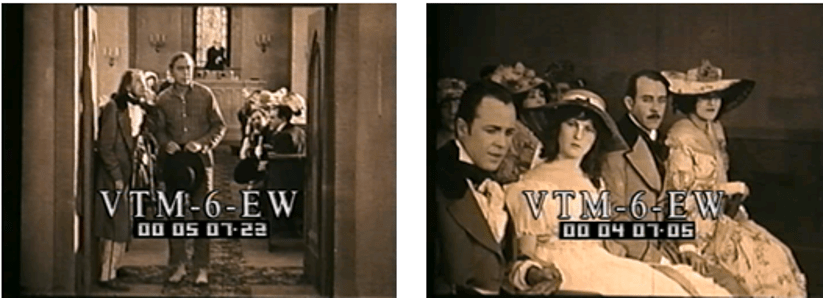

The shootout between Harry and the leader of the cattlemen (Fig. 5.3) prefigures the ending to Stagecoach(1939) (Fig. 5.4), in which the Ringo Kid kills the men responsible for the death of his brother in a gunfight. There is a further comparison to be made between the two films, both Harry and Ringo accepting the call of family and

domesticity at the conclusion of the narrative. In both, the main protagonist is, at the beginning of their respective stories, firmly on the wrong side of the law. It is only through an act of violence that each character achieves redemption and acceptance by the community.

Cheyenne Harry is also the quintessential loner, embodying the notion of the Fordian character type as the outsider as well as a man of action. Although the evidence points towards Carey and Ford’s major contribution in developing this protagonist, Universal certainly helped to reinforce the characteristics that make Cheyenne Harry an immediately identifiable figure. The promotional materials issued by Universal Studios for the various Harry Carey

films indicate that he was specifically marketed as a man of action (Figs. 5.5 & 5.6) – although, as shown later, Carey’s off-screen image was promoted more as that of a real-life rancher – and the publicity and contemporary reviews accentuate the outsider status of Cheyenne Harry, incorporating elements of the ‘good bad man’ Western persona as well. An anonymous 1918 review of Hell Bent(1918) starts with ‘Cheyenne escapes the town of Rawhide after participating in a shooting’. A Motion Picture Newsreview of A Fight For Love (1919) describes the main character as being ‘wanted for cattle-rustling’ (Motion Picture News, 22/03/19). In Three Mounted Men (1918), ‘Cheyenne Harry and Buck Masters, a forger, are serving sentences in jail’ (Motion Picture News, 1918). In Marked Men (1919), he is ‘serving a prison sentence for robbing a train’ (Moving Picture World, 03/01/1920).

In reference to the later Fox title, 3 Bad Men (1926), J.A. Place suggests the price that Ford’s ‘good bad man’ pays in order to maintain independence and outsider status is forfeiture of any possibility of intimacy or a stable partnership with someone of the opposite sex (Place, 1973, p.25). This noticeable evolution of a key Fordian figure, from a man who is willing to forsake the way of the outlaw and become a law-abiding citizen, to that of a man who is

emotionally incapable of abandoning a life outside of the law and community, can be traced back to an earlier Ford film, Marked Men (1919) (Fig. 5.7), presumed lost. Remade by Ford as 3 Godfathers (1948), the story is very similar to that of 3 Bad Men (1926), in which the outlaws momentarily abandon a life of bank-robbing to protect the new-born baby of a dying mother.

Universal Studios obviously recognised that Ford and Carey were a unique partnership. In an age when the star was generally considered to be more important than the individuals behind the camera, the studio championed Ford’s

contribution as much as that of Carey’s, as indicated in a studio advertisement from 1919 (Fig. 5.8). The significance of Ford being feted by the studio cannot be underestimated when considering the evolution of the director’s profile from Jack Ford to ‘Jack Ford’. In acknowledging his contribution to the filmmaking process, studio materials such as this provide the opportunity to examine the evolution of Ford’s cultural position and institutional reputation. Not only is Ford now an individual as opposed to a faceless studio employee, but Universal’s promotion of him ‘provides a kind of branding, a guarantee of status’ (Brooker, 2012, p.7), which constructs him not merely as a creative individual but, in Foucault’s term, an ‘author-function’.

This particular piece of promotional material is evidence that Ford is recognised quite early on not just as an individual who directs, but also as someone who contributes equally, along with Carey, to a specific brand or type, labelled here as ‘Plain Westerns’. It should also be noted that Ford’s name comes first, emphasising his importance over that of the actor, indicating that the director was capable of stamping his own authorial credentials on the narrative, irrespective of the actor with whom he worked.[2]

Despite the heightening of Ford’s profile by the studio, this treatment did not necessarily extend to other promotional items such as posters or stills. The materials for two films both released in 1919, Riders of Vengeance and Marked Men, indicate that, in general, the prestige of the director still lagged quite a way behind the perceived worth of the of the star.[3] In the poster for Riders of Vengeance (1919) (Fig. 5.9), the director’s name is listed in the smallest of all the types used in the image.

A promotional still from Marked Men (1919) is accompanied by a caption stating that ‘the camera man is seen on the left of the picture waiting for the instructions of the producer to commence.’ The stylistic pose and the

prominent cap worn by the figure on the right of the picture (Fig. 5.10) strongly indicate that the ‘producer; is actually Ford himself., although he remains anonymous. This indifference to the correct acknowledgement of the role of the director in 1919 underlines Jacques Rivette’s observation that, ‘after the existential coup de force of Griffith, the first age of the American cinema was that of the actor; then came that of the producers’ (in Caughie, 1993, p.41).

As discussed later in this chapter, it is in the films that Ford made with Harry Carey, and the desire of the Cheyenne Harry character to reject modern civilisation, that one can trace the beginnings of the director’s traditional and nostalgic worldview, in which the future threatens to smother the mythical past. The antimonies identified by Wollen reflect this conflict between the new and the old, the opposites of ‘European versus Indian, married versus unmarried [and] East versus West’ (Wollen, 1987, p.94), embodying the struggle of the old to resist the encroaching influence of the new and the civilised.

Ford indicates his admiration for an idyllic and Utopian age in preference to that of a more contemporary society, an ideology that is expressed within the narrative of practically all of his later, more celebrated Westerns. The majority of Ford’s films with Carey, and a large number of films that followed, dwell on the past rather than contemporary settings; the values and moral standards celebrated in his films champion a brief and mythical age of civilisation that is caught somewhere between the end of the settling of the West in the 1870s, and the early part of the twentieth century.

The key traits of man of action, and the struggle between surrendering to civilisation or returning to the wilderness, as identified by Wollen, are usually associated with later Fordian protagonists such as Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath(1940), Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine (1946), Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956) and Tom Doniphon in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), but can be directly traced back to the characters that Harry Carey played for Ford. For the first couple of years at Universal it appears as though Ford is the pupil to Carey’s mentor, but by the time the filmmaking partnership came to an end, Ford’s Western protagonist was a fully formed entity that could seamlessly inhabit the other genres within which the director worked. To summarise, the evolution of the ‘good bad man’ in Ford’s work is moulded and influenced by a combination of two main factors. The first is the actor most closely associated with Ford during his tenure at Universal, Harry Carey. The second major factor is the studio itself, which was happy to market and support both Ford and Carey in producing a body of work that enabled the director to express his independent vision and explore his own characteristic themes.

Autobiographical Influences

To what extent does a director’s work express his personal history, and how do these autobiographical elements influence an auteurist approach to film? In John Ford’s case the answer can be found by the presence in his films of thematic motifs such as religion, the family unit, ritual, class, and Irishness. The constant reference to family encompasses not only the dynamics of this all-important social group, but a further sub-catalogue of themes such as disintegration of family, mother-love and the influence of the matriarch. All of these themes can be identified, albeit some of them only in embryonic form, in his Universal work. The sub-theme of the fractured family potentially reflects the gradual dissolution of Ford’s own family unit, and is a constant throughout Ford’s Universal period, whilst the emphasis on the strong matriarch mirrors the powerful influence of his mother, Barbara, or Abby as she was generally known.

The family, in Ford films, is always threatened by disruption, either from within, or by external forces such as war and enforced separation. In Ford’s depiction of the family unit, there is a distinct difference between the theme of mother-love and the portrayal of the matriarch in general, the former constituting a genre in its own right. The subject of family also embodies Ford’s regard for ritual, covering the traditional themes of eating, drinking and music as a form of communal bonding. Ford also constantly championed the plight of the common man, something he had personal knowledge of, as both his parents had working class Irish roots. The numerous Irish characters that also permeate his films are discussed in more detail in the following chapters.

The Family Unit

J.A. Place states that ‘the breakdown of the family […] is John Ford’s most anguished theme’ (Place, 1979, p.171). Coming from a large family, of which he was the youngest, it is almost certain that Ford witnessed first-hand the inevitable decline of the family unit, as siblings left the household, and age eventually reduced the influence of the parents on their children. On his return home to visit his family and make a couple of short comedy films in the process, Francis Ford confessed to a local newspaper in 1915 that, ‘[at age 24 he] arrived at the conclusion that his home city held not the inducements he believed lurked elsewhere. [He was gone for eight years.]’ (The Portland Sunday Press and Portland Sunday Times, 1915). Joseph McBride tells of John Ford admitting that ‘the reason he left his hometown was that it offered few opportunities for Irish-Americans’ (McBride, 2003, p.61).

Joseph McBride believes that Ford felt guilty ‘over the “desertion” of his parents to pursue a career at the opposite end of the country’ (McBride, 2003, p.196). This theme of self-recrimination is integral to the narrative of The Scarlet Drop(1918), in which the character of Harry Ridge, as played by Harry Carey, has to come to terms with the fact that his mother has died of starvation after he has left the family home to join a band of outlaws. The absence

of the mother is signified by the empty rocking chair that Ridge stumbles upon in the home he abandoned earlier (Fig. 5.11). As in Straight Shooting (1917), redemption is once again only possible through the creation of a new family unit, with Ridge eventually marrying and settling down.

Right from the start, the incomplete family unit is repeatedly referenced throughout Ford’s work, whether the family is fractured prior to the beginning of the narrative, as in Bucking Broadway (1917), or fragmented within the course of the film, such as in Straight Shooting (1917) and The Scarlet Drop (1918). For instance, it is almost a given in Ford’s films that daughters will not have a mother and that a son will be missing a father. This narrative device removes any resultant tension in the father and daughter or mother and son relationship, therefore emphasising the closeness of those who remain within the fractured family unit.

Ford’s early Universal Westerns tend to feature a father and daughter relationship, the exception among the extant titles being The Secret Man (1917) and The Scarlet Drop (1918). Along with Straight Shooting (1917) and Bucking Broadway (1917), the narrative of The Last Outlaw (1919) concerns a father figure looking to be reunited with his daughter after being released from jail. When he finally tracks her down, she is being courted by an unsavoury

crook. In one scene the villain is placed between thetwo family members (Fig. 5.12), the daughter yet to recognise her own father, and the position of the crook within the mise-en-scène signifying a hurdle to be overcome before the family can be reunited.

It is obvious that Ford promotes the matriarch above all other members of the group. As Brian Spittles points out, ‘the best of Fordian women are mothers [with] the maternal instinct itself often being redemptive in [Ford’s] films’ (Spittles, 2002, p.111). Indeed, a number of the director’s films feature a very strong matriarchal presence; Spittles cites the character of Ma Joad, from The Grapes of Wrath (1940), as a case in point.

In Ford’s case it is apparent that he was raised in a matriarchal family. Indeed, Scott Eyman suggests that the director’s mother, Abby, was ‘the dominant disciplinary force in the house’ (Eyman, 1999, p.39). The thematic pattern of the dominant mother-figure sidelining the influence of the patriarch may at first glance be interpreted as Ford working within the conventions of the mother-love genre. This was a popular film-type in the 1920s and early 30s, and the depiction of the tough and capable matriarch is not unique to Ford. The director does, however, bring an extra dimension to his portrayal of a strong female head of the family, in that his mothers are always stoic in the face of adversity, rarely overcome by circumstance, and prone to acts of selflessness that border on martyrdom.

Joseph McBride highlights the link between Ford’s strong mother-figures and his own mother, Abby, pointing out that, at home, ‘the mother dominated and the children’s devotion to her was as much enforced as heartfelt’ (McBride, 2003, p.44). McBride records that Ford ‘was the tenth child but only the sixth to survive. He was followed by another boy, Daniel, who lived not long past his birth’ (McBride, 2003, p.38). If, in general, it can be argued that the youngest child generally tends to be regarded as the baby of the family, and accorded more attention than his or her siblings, then Ford’s close relationship with his mother was obviously a dominating influence on both his private and his professional life.

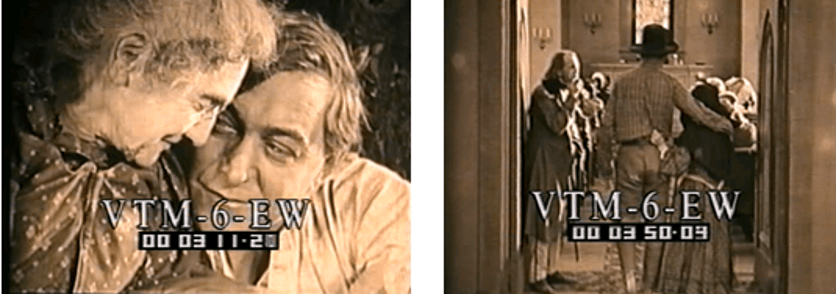

The earliest incarnation of the mother-love motif in Ford’s work can be found in the 1918 film, The Scarlet Drop (1918). Ford accentuates the loving relationship between mother and son by filming what was for him a rare

close-up featuring the couple in (Fig. 5.13). Their devotion to each other is rendered comical at times, simply by the appearance of the mother dressed in over-sized bonnet and boots, and the manner in which she holds on to the back of her son‘s shirt as they walk down the aisle of the local church (Fig. 5.14).

The theme of mother-love does not appear to be a constant in Ford’s Universal films. Evaluated in more detail in the following chapters, the motif of mother-love evolves into a key component of Ford’s late-1920s Fox work, although the theme eventually disappears from his sound films. The continued emphasis on the central role of the matriarch within the family suggests that this theme is not so much a result of studio convention, however, but more a reflection of the director’s relationship with his own mother.

Ritual

The practice of ritual in a Ford film implies Western civilisation, separating the mainly white pioneers from the other races and social groups who are usually introduced into the narrative to provide conflict. Ritual also functions to accentuate the superiority of those who indulge in communal customs and conventions, with the family unit underpinning community. A traditional Irish family such as Ford’s would have been steeped in the culture of ritual and tradition that defined their place of origin. Social rituals such as communal eating and dining, and singing, were almost certainly observed in the Ford household. Eyman writes that:

As with most Irish Catholic households of the time, rituals were contrived to give a form and shape to the daily minutiae. Every night before dinner, [Ford’s father] John Feeney would take two belts of Irish whiskey – no more, no less. ‘It never had any effect on him that you could see’, remembered his son. ‘He’d always say a blessing before his drink. So it was a religious ceremony.’ (Eyman, 1999, p.38)

Straight Shooting (1917) features numerous examples of the settlers indulging in various rituals that indicate a need to impose order on the wilderness in which they dwell. This is underlined in a scene whereby the homesteaders, who are constantly under threat from lawless land-grabbers, still find time to formally sit and eat at a

table, the act of grace, another ritual, preceding the meal itself (Fig. 5.15). The death of a son tears the fabric of the family unit apart, his loss accentuated when the sister, Joan, absent-mindedly sets a place at the table for her dead brother (Fig. 5.16). At the same time, his murder serves to create a new family unit via the redemption of the outlaw Cheyenne Harry, who abandons his lawless life upon witnessing the grief of the family as they mourn the dead boy, a sequence covered in more detail later on in this chapter.

A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman (1919)[4] features a scene in which Cheyenne Harry is ridiculed for his lack of table

manners (Fig. 5.17). The suggestion is that the protocols associated with eating must be observed diligently by all concerned. Those who do not adhere to the specifics of the ritual become disenfranchised from the rest of the community. On the other hand, in Ford’s films, drinking is depicted as a ritualised event in which all members of the community can take part, irrespective of their social background. Ford’s approach is to dilute the negative aspects of drinking by emphasising the conviviality and slap-stick violence that follows, more frequently than

not, in the aftermath of a drinking scene. In Bucking Broadway (1917) (Fig. 5.18), the drunken would-be-husband of Harry’s errant fiancée, Helen, is shown moments before violently attacking her for refusing his proposal of marriage. Ford follows the assault on the woman with a drunken free-for-all between the parties concerned (Fig. 5.19), thus neutralising the shock of the earlier violence through visual comedy.Camaraderie is also shown, on occasion, to be a consequence of drinking, with friendship sealed through the associated ritual of singing. An early example of this can be found in Bucking Broadway (1917), in which a group of cowboys commiserate with Cheyenne Harry upon learning that his sweetheart has left him. Harry’s friends indicate their empathy for his plight by gathering around a piano to indulge in the singing of a typically maudlin song, ‘There’s No Place Like Home’ (Fig. 5.20). Similarly, in Hell Bent (1918), Cheyenne Harry, who appears to be in a state of intoxication throughout most of the film, bonds with a

former foe and a shared rendition of the song ‘Genevieve’ (Fig. 5.21). [5] The song also features at the end of the film; his friend sings it to Harry as he celebrates settling down with the girl whom he eventually rescues from her life as a reluctant showgirl.

Many of Ford’s films are informed by the director’s obvious love for traditional Irish and folk music, with music frequently inserted into the storyline almost from the beginning of Ford’s directing career. In a sequence from Straight Shooting (1917), a group of outlaws are chastised by their leader for trying to relax by playing a record on his phonograph. There is no indication in this scene as to the music the outlaw wants to play, but the implication

is that music and song are not to be indulged in by those outside of community or the law (Fig. 5.22). Dancing does not feature very much in the surviving Universal titles. In Hell Bent (1919) it is depicted only within the confines of a saloon (Fig. 5.23), and involves a single dancer performing for a group of spectators, rather than a shared communal experience.

Religion

On the subject of Ford’s Catholicism, his biographers variously record that ‘he was a devout Catholic’ (Eyman, 1999, p.105), and ‘very religious’ (Eyman, 1999, p.173). On being asked by Peter Bogdanovich, ‘Are you Catholic?’, Ford answered ‘I am a Catholic, but not very Catholic’(in McBride, 2003, p.61). Although this suggests a certain ambiguity on behalf of the director toward his commitment to the Church, his films – especially those he made prior to the mide-1920s – are not so cryptic when it comes to the question of religion.

Although religion is not overtly present in Ford’s Universal films, the religious ritual of burial does make an

appearance early on in Straight Shooting (1917).A family gather around the grave of a young boy shot to death by a hired gunman (Fig 5.24). Ford’s mise-en-scène utilises the shape of the cross in the positioning of the body of the dead boy (Fig. 5.25), similar to the image shown in the previous chapter from the Francis Ford film, Three Bad Men and a Girl(1915), suggesting that the director’s religious sensibility is engaged cinematically at a very early point. The scenes concerning the death of the boy are full of religious symbolism; the young man falls into the water as he is shot, his martyrdom underlined as he is baptised at the moment of death.

As mentioned earlier, the conversion of Cheyenne Harry from hired killer to friend of the oppressed takes place at the graveside of the murdered boy. This sequence features one of the very rare examples of Ford employing the camera to convey the emotional state of a character, as the point of view shot is misted to simulate the

tears in Cheyenne Harry’s eyes (Figs. 5.26 & 5.27).

Referring to the screening in Montreal in 1967 of a newly discovered print of Straight Shooting (1917), Sarris observes that:

more than a few spectators were startled by Harry Carey’s tears […]. The spectacle of a man’s sobbing seemed not only unmanly but mythically inappropriate […]. Ford was demonstrating as early as 1917 that there was a distinction between what he rendered unto the genre in the currency of conventions and what he rendered unto himself in the coinage of feelings. (Sarris, 1975, p.22)

The fact that the conversion of the lawless gunfighter takes place at the site of a funeral resonates on a number of religiously symbolic levels, as Harry experiences a divine reformation of character whilst witnessing the holy ritual of Christian burial.

Ford’s characters, particularly those in his Westerns, are portrayed as churchgoing, God-fearing people. The church itself is looked upon as more than just a place of worship. It is also treated as a primary hub of the community for socialising and maintaining contact with other members of the same social group, as Ford echoes the role of religion in the lives of his Irish forebears. He references the importance that the church plays in the lives of ordinary people by having the mother of Harry Ridge, in The Scarlet Drop (1918), declare that ‘tomorrer, sonny boy, is yer birthday, an we-all ‘ll be celebratin’ by goin’ ter church’. Ford’s professed uncertainty regarding his own religious convictions manifests itself in By Indian Post (1919), suggesting that the director’s early worldview is one in which holy rituals do not necessarily need to be performed within the physical walls of a church. A man of the cloth administers wedding vows from the balcony of his house to an eloping couple in the street below (Fig. 5.28).

The holiness of the occasion is underlined by the mise-en-scène of the pulpit-like shape of the balcony and the pious, high-collared white vestment of the preacher – which is actually a nightshirt. Having previously been referred to as a ‘parson’, it is obvious that the preacher is non-Catholic. This implies either reluctance on behalf of Ford to potentially offend the studio and audience members of differing faiths or, at this point in his career, a lack of confidence in introducing the theme of Catholicism into the narrative, something that would not deter him later on as he started to gain his own artistic independence.

Class

Although Ford once said of his childhood that ‘we were a comfortable, lower middle class family’ (in Gallagher, 1988, p.2), his parents were most definitely working class. During an interview at UCLA in 1964, he stated, ‘I am of the proletariat. My people were peasants. They came here, were educated’ (in Peary, 2001, pp.62-63). It must be assumed that the working class credentials of his mother and father informed the nature of some of the director’s characters in the early films, with the majority of Fordian figures occupying the lower end of the social scale. That is not to suggest, of course, that Ford was the only director of the time concerned with the plight of the less well-off; Chaplin’s incarnation as the ‘little man’, for instance, used an archetypal working-class character for its comedic and sentimental value. However, Ford’s portrayal of the working-class man is somewhat more complex. His characters strive to better themselves on a personal level, perhaps reflecting the director’s own social aspirations; yet they firmly remain in, and even embrace, their own class by the end of the narrative.

Ford and Harry Carey, through the figure of Cheyenne Harry and other characters, portray their protagonists as saddle tramps of questionable morality, eschewing the more traditional approach to the cowboy as heroic loner and upholder of the law. Cheyenne Harry is variously portrayed as a hired gun in Straight Shooting (1917), an outlaw in The Secret Man (1917), a cow-puncher in Bucking Broadway (1917), and a convict in Three Mounted Men (1918). At no point do any of the characters played by Carey attempt to hide their background, even when the issue of class is brought into the open.

In Bucking Broadway (1917), the difference in class between Cheyenne Harry and the villainous cattle buyer, Thornton, is depicted through materialism; Harry’s girlfriend is tempted to the big city by the promise of hotel living, social parties and automobile-driving businessmen. The implicit message is that the corrupt classes are a by-product of civilisation, which inevitably favours the moneyed groups over the lower class. The social mix of the church in The Scarlet Drop (1918) highlights the disparity in class between the dirt-poor, shoeless Harry Ridge (Fig. 5.29), waiting in the doorway of the church to accompany his equally socially disadvantaged mother, and

those who look with disdain upon the less well-off (Fig. 5.30). Class also becomes an issue when, at the outbreak of the Civil War, Harry Ridge tries to join the Union army. Firmly rejected by those outside of his social circle as ‘white trash’, he is cast ignominiously into the street, his exclusion from the army on the basis of class compelling him to fight for the other side (Fig. 5.31).

Social and Cultural Influences

Many of the director’s silent Universal and Fox films feature ethnic minorities, ranging from African American ‘Uncle Tom’ figures, through to Mexicans, Chinese, and Italian, and, specifically in the Fox years, the Irish. The portrayal of some of these minority groups, such as African and Native Americans, changes over time, dependent upon the prevailing social attitudes. The representation of other groups, Asian and Mexican in particular, seems to be constant and fixed across a range of films, suggesting the attitudes towards them did not change during this period.

The affirmation of white cultural supremacy as the driving force behind the settling of the West is encapsulated within Ford’s major theme of civilisation versus wilderness. The early pioneers enforced their God-given right, through the concept of Manifest Destiny, to appropriate the land from the indigenous Native Americans. As with other Fordian themes, the key motif of civilisation versus wilderness also contains a set of sub-themes – Wollen highlights East versus West in particular – and the challenges that the signifiers of modernity, such as fences and automobiles, bring to the pioneer way of life.

Ford drew inspiration from a number of artists famous for representing the culture of the West, and his admiration for the work of the well known nineteenth-century painters, Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, influenced the mise-en-scène of many of his films. It is through his regard for these and other artists such as Thomas Moran and Maynard Dixon that the thematic motif of wilderness as character evolved; Ford would adopt and develop this idea in many of his later Westerns, incorporating and expressing this personal interest increasingly through his films as he gained his cinematic independence and cultural stature.

Race and Ethnicity

Donald Bogle writes that, after the furore over the negative depiction of African Americans in The Birth of a Nation (1915),[6] never again could the Negro be depicted in the guise of an out-and-out villain’ (Bogle, 2001, p.16). The depiction of black Americans in Ford’s Universal titles would appear to support this finding, as most of these characters are either limited to comedy roles, or inconsequential to the narrative.According to Thomas Cripps, ’from 1915 to 1920 roughly half the Negro roles […] were maids and butlers, and 74 percent of them were known in the credits by some demeaning first name’ (Cripps, 1993, p.112). Cripps states that ‘‘‘White” movies still offered little gratification to black viewers. Indeed, a judge in a censorship case suggested that blacks had no recourse against racism in movies save the “silence of contempt”’ (Cripps, 1993, p.76).

Confirmation of the assertion by Cripps that black American actors were consigned mainly to socially menial roles can be found in The Secret Man (1917), the first of Ford’s surviving silent films to feature an African American character. The white jacket worn by the black actor in the foreground indicates he is a coach attendant at most

(Fig. 5.32), while the lack of dialogue or a meaningful name signifies his inconsequential place within the narrative. However, a year later, in Bucking Broadway (1917), an African American character is featured in a more high profile role. In this sequence, Cheyenne Harry purchases a suit, only to find an African American wearing exactly the same

outfit (Fig. 5.33). Harry returns to the shop, strips off the suit and pushes the shop keeper to the ground. If the owner of the other suit had not been African American, then Harry’s reaction would be seen to stem from the fact that everyone is being sold the same clothing, thus subverting his individuality. As the other figure is non-white, Harry’s anger seems to be a response to the ethnicity of his competitor, and the fact that Harry does not want to wear the same clothes as the African American character. When Harry subsequently assaults the shop keeper he is not just punishing him for selling the same suit, he is also castigating him for selling a suit that he has already sold to a black man. It is to the credit of the film that Harry does not mete out punishment to the African American character, although he does this implicitly when he roughs up the man who sold him the suit.

This scene appears at first glance to conform to the established Hollywood stereotype of the time, underlining the attitude of a society that did not look favourably upon African Americans who attempt to emulate their ‘white superiors’. Evidence suggests, however, that the Hollywood studio depiction of black Americans was actually out of step with a more liberal social attitude prevalent during the period in question. Thomas Cripps argues that ‘the cinema lagged behind [like a] plodding liberal drift, and presented social change only after it was no longer controversial’ (Cripps, 1993, p.120). Cripps attributes this to the owners of the major Hollywood studios, suggesting ‘the most liberal Jews who managed the studios had no way of knowing how to render black life honestly’ (Cripps, 1993, p.119).

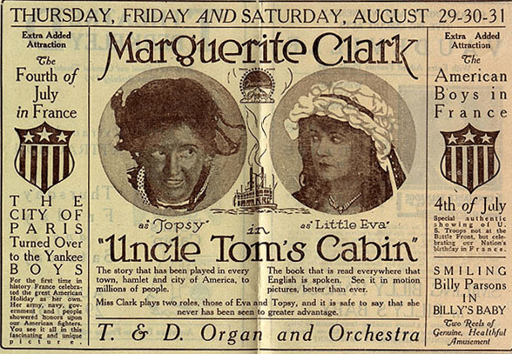

The potential for interaction with black ethnicity, and the subsequent fear of miscegenation, is referenced in the narrative of The Scarlet Drop (1918), in which it is suggested that the mother of the heroine, Molly Calvert, is an African American. Although a large section of the film is presumed lost, existing footage features a female character of mixed-race who may be plotting intrigue against her masters. This figure appears to be played by an actress who has been made up to look non-white, implying that the practice of portraying ethnic characters with a non-ethnic

actor (Fig. 5.34), as seen a few years before in The Birth of a Nation (1915), was still deemed to be acceptable by both the studio and the cinema audience. Photographic evidence from a film made a year later, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (J. Searle Dawley, 1918), confirms that this form of screen representation continued through the rest of the decade, as a white actress by the name of Margeurite Clark played the dual role of the white character Little Eva, and the African American child slave Topsy (Fig. 5.35).

On the subject of Native Americans, Ford’s attitude towards their depiction would undergo a gradual change in later

years, although their appearance in Bucking Broadway (1917) (Fig. 5.36) shows that, in the early days at least, the director was content to show them as figures of fun, and, in this case, the target of amusement for a group of Mexicans. There are two points worth highlighting regarding the Native American figures in this film. First of all, they are costumed in a combination of native wear and clothing appropriated from the white community. The implication is that they have already accepted the values of the land-owners in order to integrate themselves within a dominant social group. The second observation is that the Native Americans inhabit the same space as that of the Mexican and white characters, suggesting tolerance towards this particular ethnic minority. This is presumably because they pose no threat to white society; the settling of the West had reduced Native Americans to the point where they were depicted as almost child-like in demeanour and behaviour.

One significant aspect of the manner in which Native Americans are portrayed in Ford’s films is that, in the majority of both his silent and sound Westerns, the director, on occasion, employs real members of this ethnic group to play themselves, adding an element of authenticity to an otherwise stereotypical portrayal of a once proud and revered race. Although this method of casting indicates a small progressive step forward in the onscreen depiction of Native Americans, Benshoff and Griffin point out that, ‘by the 1920s […] Native American actors were forced to accept smaller and increasingly stereotyped roles’ (Benshoff and Griffin, 2009, pp.107-108).

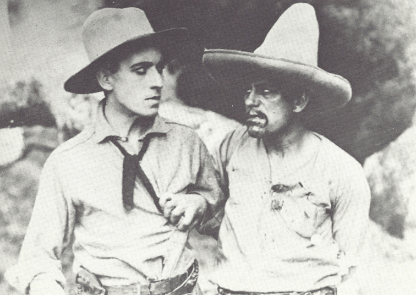

The portrayal of other ethnic groups in Ford’s silent films hardly evolves at all during the Universal years. For example, in The Secret Man (1917), the Mexican husband and wife kidnappers are depicted as the obvious villains

of the narrative (Fig. 5.37), with the husband portrayed as a wife-beating criminal. In Bucking Broadway (1917), the Mexican character is presented as a barely integrated member of the community, allowed to occupy the same room

as his fellow cow-punchers, but separated from the main group who sit huddled together a few feet away (Fig. 5.38). Upon uttering a disparaging remark about Cheyenne Harry’s interest in the daughter of the ranch owner, the

leader of the cowboys, Buck Hoover, delivers a punch to the errant Mexican, after which he is summarily chased out of the cabin. The ethnicity of this character lends his remarks – ‘he’s only a simple ranch hand; it must be more than friendship’ – an element of salaciousness that would not be implied if he were white (Fig. 5.39). Later on, in Hell Bent (1918), the Mexicans are depicted in purely stereotypical terms as unshaven, sombrero-wearing drunkards (Fig. 5.40).

More often than not, Ford’s Universal films seem to favour the use of genuine Mexican actors and extras. Prior to this it would appear that, within Universal Studios, this particular ethnic group was mainly portrayed by white actors, as the image of Lon Chaney playing a character called The Greaser in The Tragedy of Whispering Creek (Allan Dwan, 1914) shows (Fig. 5.41).

The surviving footage of A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman (1919) depicts two nationalities that rarely feature in later Ford films, a Japanese man-servant (Fig. 5.42) and an archetypal Englishman, a figure known as the Earl of Jollywell (Fig. 5.43).

Ford’s antipathy towards the British is highlighted for the first time, with the Earl portrayed as an arrogant monocle-wearing aristocrat, a type that Ford would employ in a later silent film, Hangman’s House (1928).[7] An adaptation of the scenario in Boys’ Cinema suggests that the Earl competes with Cheyenne Harry for the affections of the heroine, Helen (although she is referred to as Mary in the magazine story). The English stereotype as vain and disdainful is emphasised in the adaptation, the character described as someone ‘whose sporting abilities were not remarkable – save, perhaps, by their absence […]. Piccadilly was more his style, and he mourned for it every day’ (Anon, 1922, p.4).

Again, as with the representation of Mexican characters in Ford’s Universal titles, there appears to be a preference to use genuine Asian actors, whereas other Universal films tend to feature white actors playing Oriental protagonists. The ubiquitous Lon Chaney, one of the studio’s biggest stars, appears alongside the American actor E.A. Warren, respectively playing the parts of Ah Wing and Chan Lo (Fig. 5.44) in Outside the Law (Tod Browning,

1921). The stereotypical inscrutable Asian can also be found in another Universal film, Reputation (Stuart Paton, 1921), in which the white actor James McLaughlin plays the owner of an opium den (Fig. 5.45).

The next chapter considers how Ford’s representation of ethnicity in the films he made for Fox began to take more of a coherent shape, particularly that of both Native and African Americans, and how the depiction of these and other minorities resonated with the prevailing attitudes of white America towards ethnic groups in general.

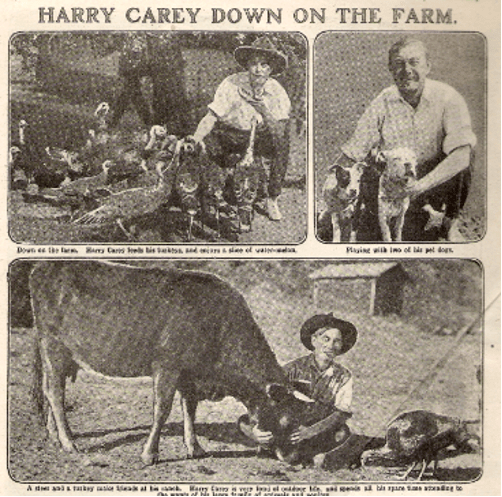

Civilisation and Wilderness

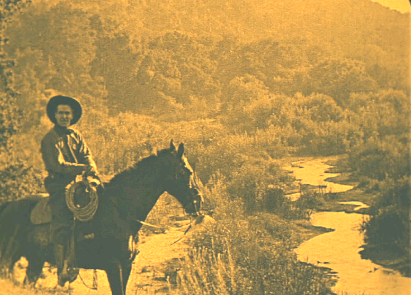

Ford’s early films show his inclination towards wilderness over civilisation. Despite the cultural history of a country that, up until the mid to late 1960s, championed the settling of the West as an achievement of obviously huge historical importance, Ford and Harry Carey both embraced a lifestyle that involved spending time away from the trappings of civilisation and progress. The studio itself promoted Carey as an outsider, living a Western existence similar to the Cheyenne Harry character. Carey’s preference to live on his own ranch in Newhall far away from the

mainstream of Hollywood glamour is attested to by the publicity shots from 1920 (Fig. 5.46).

Ford threw himself into this outside lifestyle as well. ‘Jack vacated his Hollywood bachelor apartment and went to stay on the three-acre ranch with the Careys […]. There was only one bedroom and Jack and Harry preferred to sleep outside in bedrolls’ (McBride, 2003, p.109). As McBride points out, ‘the line between illusion and reality in the filming of Ford’s early Westerns was virtually nonexistent […]. They rode on horseback to all-purpose locations around Newhall […] living a rugged life much like that portrayed in their movies’ (McBride, 2003, pp.106-107).

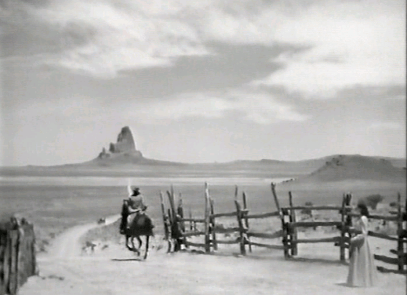

Ford and Carey’s partiality for life in the great outdoors is translated to the screen through the figure of Cheyenne Harry. Like many of Ford’s characters, Harry wavers and equivocates when confronted with the possibility of turning his back on the wilderness for a more settled life. For instance, a scene in Straight Shooting (1917) prefigures a

similar one from The Searchers (1956), in which the love of Ethan Edwards for his brother’s wife (Fig. 5.47) is observed silently on the sidelines by Reverend Samuel Clayton. Similarly, Harry’s suppressed emotion (Fig. 5.48) for the young girl, Joan, who is already betrothed to someone else, is witnessed by another who, like Clayton,

keeps his observations to himself (Fig. 5.49). The comparison of this sequence with The Searchers (1956) is further underscored by the manner in which the other characters tend to their tasks in the cabin, oblivious to the unspoken emotional turmoil unfurling in their midst.

The conflict in the community between settlers and wanderers is summed up once again through the character of Cheyenne Harry in Bucking Broadway (1917). A title card proclaims his obstinate opposition in contributing towards the subjugation of the wilderness, stating, ‘Me, a farmer? No. I belong on the range’, a clear indication of the character’s desire for a life free of the restraints of civilisation. This philosophy is underlined visually with the

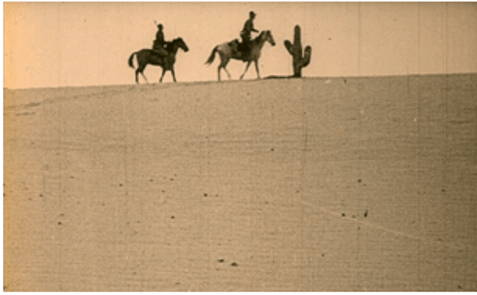

foregrounding of a number of figures against the wilderness (Fig. 5.50), with the lone individual superimposed against a landscape that complements, rather than overwhelms, the horse-bound men.

As previously mentioned, the motif of civilisation versus wilderness encompasses the sub-themes of East versus West, and the modern versus the past, and the recurrence of these themes in Ford’s films during the period 1917 to 1921 provides an important example of his early, evolving auterist expression. In Bucking Broadway (1917), for instance, Harry is compelled to leave the familiar environment of the wilderness for the city to rescue his girlfriend from Thornton, the villainous cattle-dealer. Harry, a man of the West, adopts an East-coast guise by dressing in a suit when in the city, the incongruity of Harry’s attire, rounded off with a ten-gallon hat, epitomising the

opposites of East and West (Fig. 5.51).

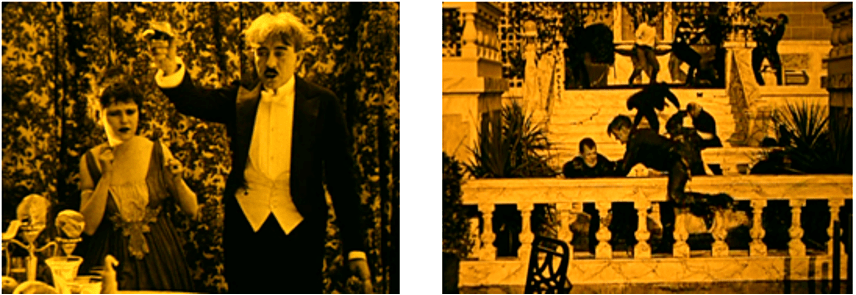

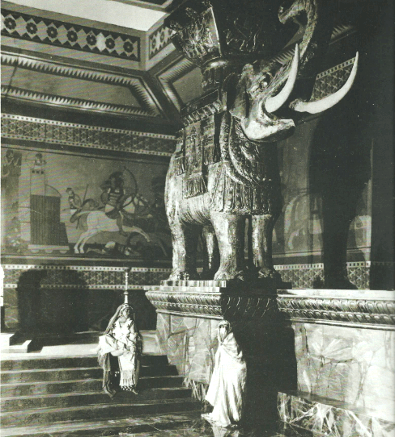

In the climax to the film, East and West collide in a fist fight that underscores the decadence of the city and its inhabitants, and the intrinsic honour of the men of the West. As Phil Wagner points out, ‘the East / West paradigm is inverted when the cultured citizens of New York instigate a riotous brawl with the rugged cowboys of the frontier’ (Wagner, 2009, p.5). Harry and his cowboy friends fight not only for their own honour, but also for the reputation of the naive fiancée, Helen, who has been tempted to follow Thornton back to the city. Fittingly, the fight takes place against the background of a man-made construct that signifies the falsity of life in the metropolis and the empty

promises that would no doubt have eventually greeted Harry’s girlfriend (Fig. 5.52). The statues and stone columns imply decadence, corruption and decay, with the battleground between cowboy and city-dweller reminiscent of a lost and ancient world, long consigned to the past.

The conflict between the past and the present, and nostalgia for a way of life that is no longer possible in an increasingly modern world, lies at the heart of a number of Ford’s silent Westerns. The motor car, along with the urbanised city and its stone-built high-rise dwellings, also signifies the clash between the new and the old, with the

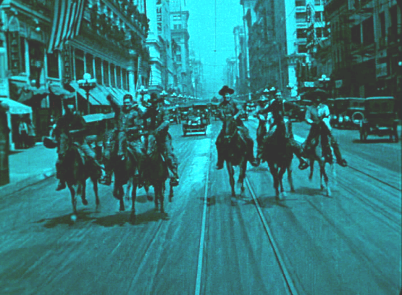

vehicle featuring in a number of Ford’s Universal films. Thornton eschews the horse for a motor car (Fig. 5.53). The image that follows epitomises the contrast between the city background of the car driver, and Harry’s wilderness environment (Fig. 5.54). The contradiction between Harry’s natural habitat and the strange world he is forced to enter is further highlighted in a scene featuring a group of cowboys riding through the traffic in New York. East

and West collide when the riders gallop through the traffic (Fig. 5.55) surrounded on either side by a man-made canyon of high-rise buildings.[8] They temporarily reclaim land that is now literally concreted over in order to provide smooth transportation for the horseless carriages, with Harry and his friends easily overtaking the cars on their mounts.

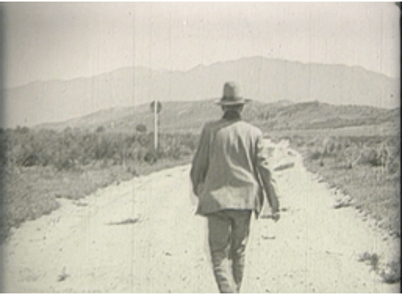

The adoption of the car in place of the horse delineates the difference between the heroic intentions of the Old World, and the corrupt values of modernisation and technology. For example, in The Last Outlaw (1919), Bud Coburn is released from jail after ten years into a world that is vastly different from the one he knew before. He

barely escapes being run down by a motor car (Fig. 5.56), the scene accompanied by a title card implying that Hollywood, even in the early days of the industry, acknowledged that the West was already consigned to the past (Fig. 5.57). In the same film, the call of the wilderness is far stronger than the strange new world to which Coburn

has returned after being incarcerated for so long (Fig. 5.58). The motor car is now common-place, literally forcing him from the trails he used to ride in the past. Coburn’s only option is to turn his back on progress and follow a path back towards a wilderness more conducive to his role as an outsider.

A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman (1919) positions the motor car between the opposing forces of past/wilderness and modernity/civilisation. Cheyenne Harry and his co-riders are out of step with modern life as they ride through the streets of the city in Bucking Broadway (1917). The opposite is implied in A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman (1919) when

Harry, by blocking the trail with a fallen tree (Fig. 5.59), renders the car, and by implication its drivers, redundant outside of the city.

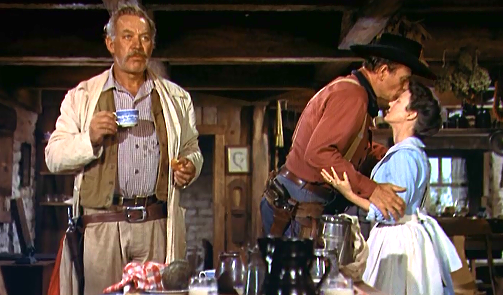

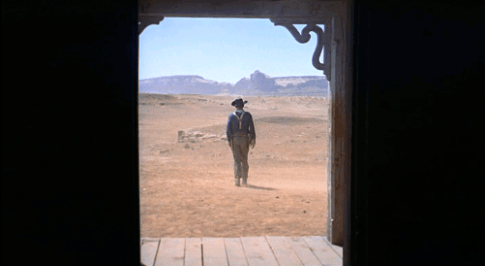

Kitses points out that, Ford ‘is a contrarian [and] his work is pervasively marred by paradox and perversity’ (Kitses, 2004, p.33). The theme of civilisation versus wilderness is a perfect example of this; Ford’s characters, most obviously in the Westerns, are constantly at odds with the civilised world as much as they are fighting for survival against the hostile forces of nature. The paradox that Kitses identifies is highlighted in later Ford films such as Stagecoach (1939), in which a group of assorted passengers traverse the wilderness that lies between the towns of Tonto and Lordsburg. As both the prostitute Dallas and the Ringo Kid find out, life in each of these towns is just as dangerous, if not more so, as the wilderness into which the passengers are cast. Dallas is banished from Tonto by a collection of self-appointed guardians of morality intent on cleaning up the town (Fig. 5.60). At the end of the

journey, after the Ringo Kid has dispatched the killers of his brother, he and Dallas, like so many of Ford’s characters, express their desire for the wilderness, riding off into the landscape to start a new life together on the Kid’s ranch (Fig. 5.61).

In My Darling Clementine (1946), Wyatt Earp and his three brothers appear to literally spring from the landscape out of nowhere at the beginning of the film, only to return back to the wilderness once Earp’s task to cleanse the town of Tombstone of violence is complete. By the time Earp takes his leave the group of brothers are reduced to two, victims of the civilisation into which they attempted to assimilate themselves. Although the Earps have not failed the community in defeating the lawlessness that pervaded the town, once their mission is accomplished the

brothers are banished into wilderness, disappearing back into the landscape (Fig. 5.62) from which they came. In John Ford’s world, the wilderness will nearly always prevail.

The key Fordian theme of civilisation itself is a reference point for the motif of fences and barriers that Ford employs numerous times in the mise-en-scène. Fences feature prominently in the director’s Westerns; they signify, among other things, the obvious encroachment of community and civilisation. A fence can also be construed as a barrier to the outsider, or as an object of protection for those outsiders who wish to join the community. As Eyman and Duncan point out, ‘to be part of the family or community, the central character must be inside the door or the fence’ (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.17).

The wilderness in Ford’s films is separated from civilisation by a series of barriers and fences that define the disconnection inherent in these two opposites. The first appearance of a fence in an extant Ford silent film is in Straight Shooting (1917), signifying a barrier that contains the family Cheyenne Harry is initially hired to intimidate. It threatens the stability and safety of those inside the fence, placed there by unscrupulous land-grabbers

determined to drive the family away (Fig. 5.63).

In Bucking Broadway (1917), the fence divides the outsider (Fig. 5.64), in this case the ubiquitous Cheyenne Harry, from the object of his affection, Helen, who is representative of community and family. The potential union between

Harry and Helen is threatened by the presence of Thornton, who is already comfortable on the same side of the fence that embraces Helen and a settled social group (Fig. 5.65).

The significance of a fence in Ford’s silent Westerns evolves in quite a short time from being a catalyst to conflict, to a portal between wilderness and community. Cheyenne Harry’s transition from outsider to one on the inside of community, in Hell Bent (1918), is represented by the presence of a gate and fence which he must pass through to indicate his acceptance of conformity. Early in the film Harry stands tentatively in the open gateway outside the house of the woman with whom he will eventually settle down (Fig. 5.66). By the end Harry completes the

conversion from wilderness tocivilisation, his intended wife ushering him through the open gate into domesticity (Fig. 5.67).

As with doorways, Ford will intermittently incorporate a fence to imply a barrier between two characters in

opposition, either emotionally or physically. In TheSearchers (1956) (Fig. 5.68), Martin Pawley’s girlfriend, Laurie, becomes angered at his refusal to abandon the search for his tainted half-sister, and the wooden structure of the fence functions as an overt physical obstruction to their relationship. Tag Gallagher identifies a more spiritual significance to the existence of a fence in Young Mr Lincoln (1939), describing the grave of Ann Rutledge as a ‘netherworld beyond the fence in which reality beyond reality is found’ (Gallagher, 2006, [n.p.]). It is not a barrier in this sequence, but a gateway through which Ford’s characters communicate with each other, the thematic motif of

communing with the dead intertwined andreinforced through the application of a Fordian visual pattern as well (Fig. 5.69).

Figuration and Landscape

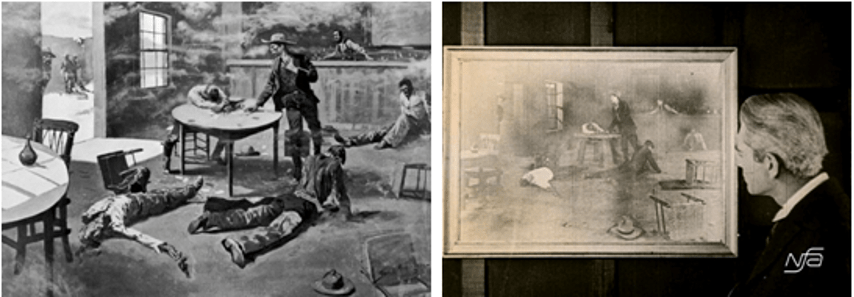

This section considers the influence upon the mise-en-scène of Ford’s work, in particular his silent and sound Western films, of artists such as Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, Charles Schreyvogel, Maynard Dixon, and Thomas Moran. Remington was a huge influence upon Ford when it came to aspects of Western iconography such as the lone cowboy rider, Native American and stagecoaches, as well as the action sequences that populated Ford’s Westerns. However, as Edward Buscombe points out, what Remington ‘chose to record was the life of hard riding and hard fighting’ (Buscombe, 2001, p.158), and it this aspect of Remington’s work, as well as that of Russell and Schreyvogel, which will be highlighted first before turning to the influence of other artists such as Maynard Dixon and Thomas Moran on the place of landscape in Ford’s films.

Edward Buscombe writes that ‘Remington’s is largely a narrative art, which in certain ways anticipates cinema […]. [His] most striking pictures show events, either the prelude to an act, emphasizing narrative tension, or a snapshot of action frozen in time’ (Buscombe, 2010, pp.53-54). An example of the latter can be found in Hell Bent (1918). Ford explores the link between paintings of the West, and the cinematic representation of the subject, by bringing to life a Western scene that starts on the image of Remington’s painting, ‘The Misdeal’, before slowly evolving into a

real action shot (Figs. 5.70 & 5.71).

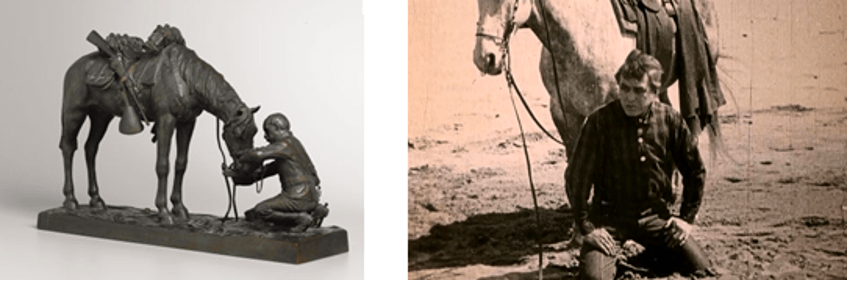

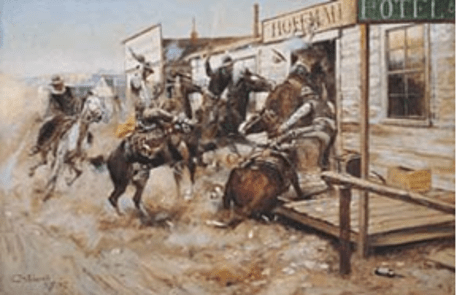

The influence of both Charles Schreyvogel and Charles Russell appears to be just as apparent as Remington’s in Hell Bent(1918), with two sequences echoing certain images of their work. The scene in which Cheyenne Harry

kneels by his horse in front of a waterhole bears similarities with Schreyvogel’s sculpture, ‘The Last Drop’ (Figs. 5.72 & 5.73), while Russell is represented in a shot capturing Harry riding into the local hotel on horseback,

seemingly inspired by Russell’spainting ‘In Without Knocking’ (Figs. 5.74 & 5.75).

Ford continued to draw upon the work of Remington and Schreyvogel in particular in his later sound films. McBride writes that the director acknowledged the ‘principal visual influence on Fort Apache (1948)’ was Remington, ‘whom he had first imitated in the 1918 Western Hell Bent’ (McBride, 2003, p.448). One of many examples of the influence that a Western painter can have on the action shots in Ford’s films can be found in a picture by

Charles Schreyvogel, entitled ‘Dawn Attack’ (Fig. 5.76). A similar scene appears in The Searchers (1956) (Fig. 5.77), in which a group of Texas Rangers descend upon a Comanche village at dawn. McBride quotes Ford, who recalled, ‘[M]y father kept a copy of a collection by Schreyvogel close by his bedside, [Ford] pored over it to dream up action sequences for his films’ (in McBride, 2003, p.449). [9]

On the subject of landscape in Ford’s films, Edward Buscombe writes that,

what Ford manages to make the landscape mean owes much to what artistic and photographic discourses had previously inscribed upon it […]. Ford’s framing of the landscape to exert the maximum contrast between its vast distances and the smallness of the figures that populate it is a clear echo of nineteenth-century photographic practise. (Buscombe, 1998, pp.125-126).

An early example of this contrast between landscape and the individual can be found in Bucking Broadway (1917) in which Cheyenne Harry is positioned against the rolling hills of cattle country, the foregrounding of the protagonist suggesting his supremacy over the vast hills and mountains in the background, rather than the other way around. Harry’s elevated status as he looks down into the valley below also highlights his command of, or at the very least,

empathy with, landscape and wilderness (Fig. 5.78).

By 1918, in Hell Bent, the director was using landscape to establish location and a sense of place within the

mise-en-scène (Fig. 5.79). Ford attempts to accentuate the remoteness of his characters in the desert by placing his protagonists on the horizon. As Buscombe suggests, ‘the desert aesthetic was tailor-made for Hollywood […] and desert scenery was right on the doorstep. William S. Hart frequently favoured desert settings for his films, as in

The Scourge of the Desert (1915) and The Desert Man1917) (Fig. 5.80)’ (Buscombe, 2000, p.16).

An example of the artistic and photographic discourses that Buscombe refers to can be found in the imagery produced by the nineteenth-century landscape painter Thomas Moran, and the early Western photographer,

William Henry Jackson. Moran’s painting, ‘Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone’ (Fig. 5.81), produced in 1872, owes much to Jackson’s photograph (Fig. 5.82), also entitled ‘Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone’, and taken a year earlier. Both images encapsulate a populist view of the West that was eventually adopted in the mise-en-scène of the

Western form in general. Certainaspects of Moran’s ‘An Indian Paradise’ (Fig. 5.83), for example, can be discerned in the opening sequence to Ford’s 3 Bad Men (1926) (Fig. 5.84). Both images are replete with running water foregrounded in the frame against the backdrop of a mountain range that underscores the vastness of the landscape.

Ford continued to use landscape to denote the vulnerability of the individual against the power of unbridled nature in his later sound films with reference to other painters of the West, such as Maynard Dixon, whose desert

paintings ‘Desert Journey’ (Fig 5.85), appears to be reflected in the mise-en-scène of Ford’s 3 Godfathers (1948) (Fig. 5.86).

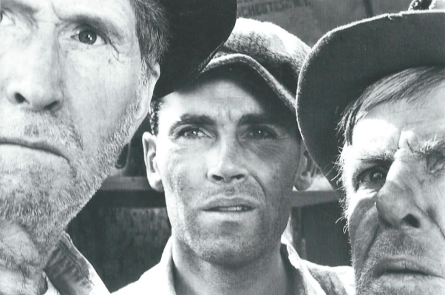

Regarding the influence of other artists on Ford’s later sound work, it should be pointed out that the Depression-era

photographic images of Dorothea Lange (Fig. 5.87), who was coincidentally married to Maynard Dixon, served as the inspiration for certain sequences in The Grapes of Wrath (1940) (Fig. 5.88).

In terms of actual location itself, Ford’s penchant for recycling landscape imagery, as demonstrated in his later Westerns through the use of Monument Valley, is apparent almost from the start of his career. Beale’s Cut, a

location he used at least three timesin his silent films, first appears in Straight Shooting (1917) (Fig. 5.89),[10] and also features in his first sound Western, Stagecoach (1939) (Fig. 5.90). Ford’s use of Monument Valley in his later sound films will be covered in more detail in the following chapter, specifically the section on landscape. Suffice to say, as Edward Buscombe suggests, ‘Monument Valley has now come to signify Ford, Ford has come to be synonymous with the Western, the Western signifies Hollywood cinema, and Hollywood stands for America’ (Buscombe, 1998, p.120).

Technology

It is not just Ford’s personal and biographical experiences that need to be evaluated when considering questions of authorship. The impression upon his work from external forces such as technology, as suggested by Edward Buscombe, must also be taken into account. This section considers the extent to which factors such as camera mobility, lighting and set design shaped the mise-en-scène of Ford’s silent films. The effect of technological advancement upon the aesthetic style of Ford’s films will be placed into context by comparing how technology also shaped the work of other contemporary directors of the time. Films such as Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914) and Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1916) show that innovative camera movement and large set design existed in films prior to the beginning of Ford’s directing career, whilst The Blue Bird (Maurice Tourneur, 1918) and The Toll Gate (Lambert Hillyard, 1920) demonstrate a similar approach to lighting and set design as that adopted in Ford’s work during the years 1917 to 1920.

Cameras, Camera Mobility and Lenses

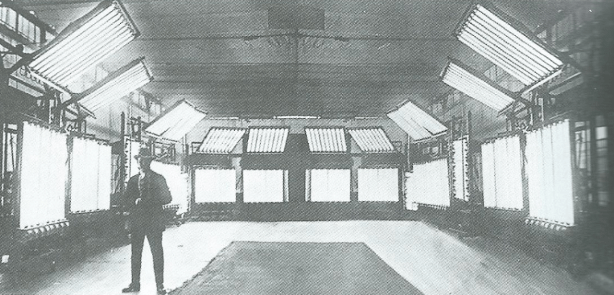

Brian Coe writes that, ‘The Bell & Howell cameras have remained in almost constant use ever since their introduction, with only minor changes in design’ (Coe, 1981, p.84). David Bordwell and Janet Staiger maintain that the Bell & Howell, which was ’put on the market in 1909, eventually became the most popular 35mm camera of the silent era’ (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002, p.252). The following image shows a scene [11] being filmed

with a Bell & Howell camera at Universal a year before Ford began his directing career for the studio, providing evidence that this particular piece of equipment was probably in use during Ford’s tenure (Fig. 5.91). The image will be discussed again in more detail in this chapter in the section on lighting and set design.

As can be seen, the Bell & Howell equipment was not designed for mobility, therefore limiting the options of the early silent film directors when attempting to capture kinetic movement and action. According to Barry Salt, prior to the 1920s, ‘exterior action scenes were the likeliest place to find camera movements’ (Salt, 1983, p.153), and Ford’s early silent films certainly confirm that. Before examining this statement in more detail, however, it is worth considering even earlier examples of camera movement from which directors such as D.W. Griffith drew their own inspiration.

The silent Italian epic Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914) influenced the work of D.W. Griffith in a number of ways, from camera movement through to set design, Kristin Thompson suggesting that the film ‘popularized camera movement in 1914 by using slow tracking movements that ordinarily did not follow characters but instead served to show off the deep, impressive sets’ (Thompson, 1998, p.264). The American director adopted some of Pastrone’s camera techniques two years later in his own film, Intolerance (1916), and in the process most certainly concentrated audience attention on the ‘deep impressive’ Babylonian sets. As Kevin Brownlow confirms, ‘Griffith had been impressed by those subtle camera movements in Cabiria(Giovanni Pastrone, 1914)’ (Brownlow, 1979b, p.71). The subtle camera movements Brownlow refers to can be found in a number of scenes in Pastrone’s film. For example, a slightly hesitant panning shot follows the trail of a boat sailing along the coast as it moves from screen

right to screen left (Figs. 5.92 & 5.93).

More discernible and perhaps more innovative than this panning shot is a sequence in which the camera dollies in

on a mother and child in a busy market place (Figs. 5.94 &5.95), and then, after a few seconds, pulls back to the original starting point of the shot (Fig. 5.96).

As Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson point out, ‘Under the influence of the Italian epics that were popular […] in the early to mid-teens, some directors and cinematographers tried using tracking and even crane shots […]. Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914) especially caught filmmakers’ attention, and the slow track independent of figure movement came to be known as the “Cabiria movement”’ (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002, p.228).

To prove the point, camera movements such as these, along with a 40 second tracking shot from Cabiria (1914) in which the hero of the film, Maciste, investigates the supplies of food and wine available to him whilst hiding from

The Phoenician army (Figs. 5.97 & 5.98) [12], can also be found in the later Griffith film, Intolerance (1916).[13] One scene in particular, an uninterrupted sequence running for approximately 42 seconds, opens with a shot on the famous city of Babylon set before the camera descends on a specially built crane to stop on a group of extras

making their way across the giant courtyard which forms the centrepiece of the structure (Figs. 5.99 & 5.100).

Whilst the majority of shots in Ford’s work at this point in his career are mainly static in form, and camera movement quite rare, when it does occur, the scene is usually brief, and always exterior. A group of riders makes its way down

a steep ridge (Fig. 5.101),with the camera following the figures as they level out on the canyon floor (Fig. 5.102). It should be pointed out, however, that a similar sequence can be found in an earlier film, Hells Hinges (William S.

Hart, 1916), in which the camera traces the movement of a stagecoach as it makes its way down a winding road (Figs. 5.103 & 5.104). Both sequences establish a sense of place for the onscreen characters and audience alike, negating the need to follow the sequence with an establishing shot to indicate where the riders are actually located. This suggests that directors such as Ford and Hart are already engaging with the idea of filming action in one complete take without recourse to any close-ups, a method that Ford in particular adopted in many of the Westerns he went on to direct, both silent and sound. A later film starring Hart, but not directed by him, The Toll Gate (Lambert Hillyard, 1920), does not contain any extended mobile shots at all, apart from a slight movement of the camera that appears to be almost accidental, suggesting that not all Hollywood directors of the time fell under the innovative spell of films such as Cabiria (1914).

Bucking Broadway (1917) provides another example of a moving camera shot, in which Cheyenne Harry’s friends gallop to his rescue down Broadway, with the camera presumably mounted on the back of a moving vehicle. Ford was obviously not the first director to consider filming mobile action shots using this particular technique. As Bordwell and Thompson point out, in The Birth of a Nation (1915), the director D.W. Griffith ‘mounted his camera on a car to create fast tracking shots before the galloping Klan members in the climactic rescue sequence’ (Bordwell and Thompson, 2003, p.74). Ford, however, appears to display an ambivalent attitude towards incorporating movement in the scene from Bucking Broadway (1917), implying uncertainty as to when the technique should be employed. The horsemen are initially filmed riding past the camera to both the left and the right. By the end of the sequence, it is almost as if Ford decides to experiment with a short burst of camera movement, abandoning the placement of the camera in a moving car and following the riders instead down the street in a panning shot as

they appear to the right of the frame (Fig.5.105). This inconsistency in approach implies the director is still in the process of learning the basic techniques of filmmaking, and a demonstration of how Ford’s style continued to evolve from one film to the next.

Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson write that, ‘Through the teens and twenties, the numerous guides […] give clear instructions for achieving deep focus through the manipulation of f-stops, lens lengths, and lighting conditions’(Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002, p.221), although they suggest that lens technology in the early days of silent film was restricted due to ‘standardisation of lens lengths’ (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002, p.219). This standardisation of equipment appears to limit the opportunity for directors such as Ford when attempting to capture characters in detail in the distance. For example, in Straight Shooting (1917), the filming of

objects in the distance (Figs. 5.106 & 5.107) inevitably cannot match the suggestion of seclusion, and the underlying thematic motif of civilisation versus the wilderness that the director captured in later sound films such as

Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) and The Searchers(1956) (Fig. 5.108).

Barry Salt notes that ‘there was a considerable range of variation in the handling of depth of field in American films made in the earlier part of the “twenties”’ (Salt, 1983, p.187). Salt does not cover any aspect of this technology at all for the period prior to this, suggesting that an appreciative depth of field was rare in most films up until approximately 1920. For example, the distant landscape shots found in The Toll Gate (Lambert Hillyard, 1920)

(Fig. 5.109) do not appear to attempt to film figures in the distance, due perhaps to the lack of ability of the prevailing lens technology to capture an appreciative sense of depth of field with any degree of acceptable clarity.

The lack of a lens capable of filming distant objects clearly meant that Ford’s early silent efforts were limited in their ability to imply the isolation of the individual in the wilderness. Although Barry Salt suggests that ‘during the years 1914-1919 […] the first signs of the use of long focal-length lenses appeared in entertainment films’ (Salt, 1983, p.154), this particular aspect of lens technology was still evolving, as a close look at Ford’s Universal Westerns will attest. The earliest example of Ford shooting a figure on the horizon to be found in the surviving films, comparable

in composition to the director’s later work, is in The Secret Man (1917). A study of this image (Fig. 5.110) shows that Ford is forced to maintain a close proximity between the camera and the characters on the horizon, thus undermining any sense of remoteness of the characters within the landscape. There is a similar attempt to shoot

actors against the skyline in Bucking Broadway (1917) (Fig. 5.111) and A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman (1919) (Fig. 5.112), but, as with The Secret Man (1917), this visual motif is a rarity in Ford’s early Universal Westerns.

Lighting