Introduction

This chapter will consider the films John Ford directed for Fox from Just Pals (1920) to The Blue Eagle (1926), a period that ended just before the coming of sound. These films will be interrogated within the framework around theories of authorship developed in the previous chapters. The chapter also considers how Ford’s nascent auteuristapproach to his Universal work begins to evolve in the films he directed for Fox, with the antimonies and oppositional themes identified by Wollen featuring prominently in the titles he worked on between 1920 and 1926. This period also marks the point when he receives his first directorial credit as John Ford in 1923 with Cameo Kirby. In the following year, John Ford starts to evolve into the entity ‘John Ford’, as his name began to figure prominently both on the screen and off. Studio marketing materials emphasise the importance and stature of the director, these examples of external discourses confirming that Ford was beginning to occupy, in Foucault’s term, the role of the author-function. Foucault defines one of the characteristic traits of the author-function as being ‘linked to the […] institutional system that encompasses, determines, and articulates the universe of discourses’ (Foucault, 1984, p.113). In Ford’s case the institutional system is the studio, whilst the discourses are embodied by the materials that promote the director’s profile.

The key thematic and visual motifs discussed in the previous chapter will also be revisited here, and assessed for any sign of progress or evolution from their original incarnation in Ford’s Universal work. Where relevant, the motifs will also be considered in light of the institutional, autobiographical, social and cultural, and technological influences that impacted upon Ford’s growth as a studio director and as an auteur. Other patterns and themes not specifically present or material enough to be considered before will also be highlighted, including Irishness, the beginnings of Ford’s contribution towards the genre of mother-love, and his abiding passion for American history, which moves increasingly to the fore in his Fox films.

Fox Corporation

Tim Dirks asserts that the five major Hollywood studios of the early 1920s comprised Warner Bros, Paramount, RKO, MGM and the Fox Corporation. Universal, Ford’s first employer, was considered to be a ‘little studio’ (Dirks, 2007, [n.p]) along with United Artists and Columbia Pictures. Robert C. Allen quotes a Fortune article from 1930 stating that at the beginning of the 1920s ‘Fox films were not considered of major importance but were “popular and profitable”’ (Allen, 1995, p.130). Ford therefore joined Fox at a point when, in order to maintain its status as a major Hollywood studio, it needed to invest in material that would continue to find favour with a more discerning audience. This state of affairs, combined with the decline in popularity of the Western genre, led Ford to work within a number of other forms for the first time during his initial tenure at the Fox Corporation. The studio put their new director to work on filming adaptations of epic poems and famous plays of the era. Both The Village Blacksmith (1922) and The Face on the Barroom Floor(1923) were based on works by the poets Henry Wordsworth Longfellow and Hugh Antoine D’Arcy respectively. Cameo Kirby (1923), Hoodman Blind (1923), Hearts of Oak (1924), Lightnin’ (1925) and Thank You (1925) were all adapted from popular plays.

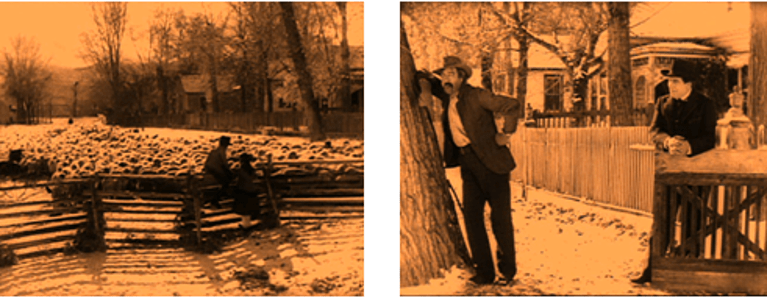

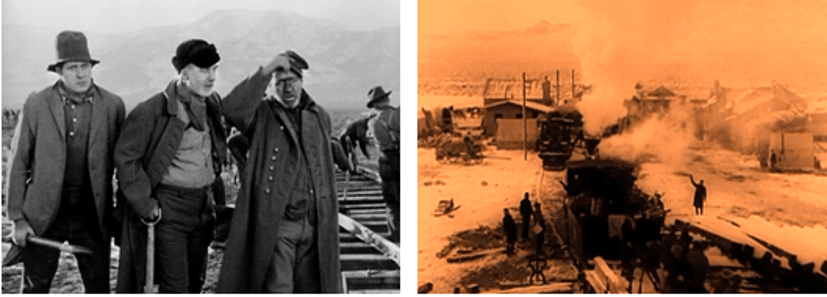

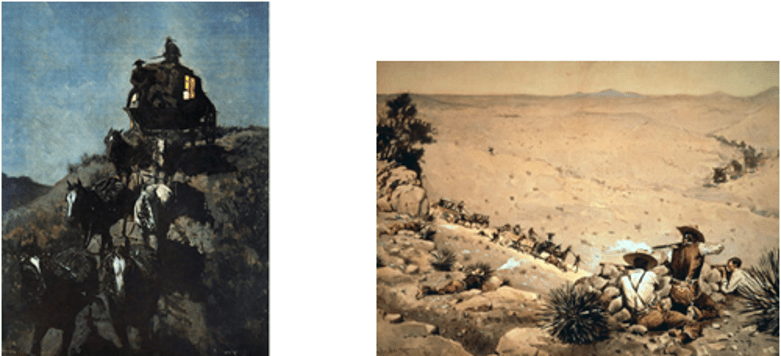

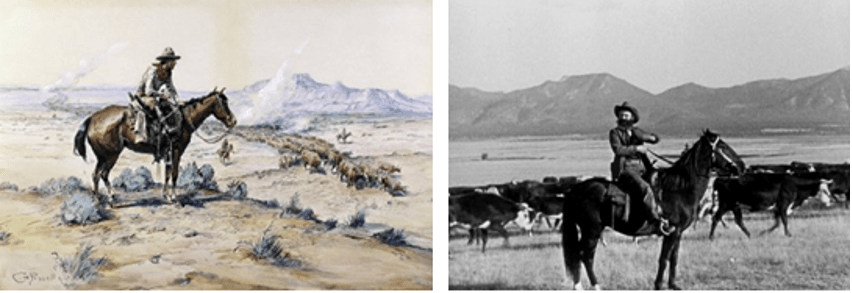

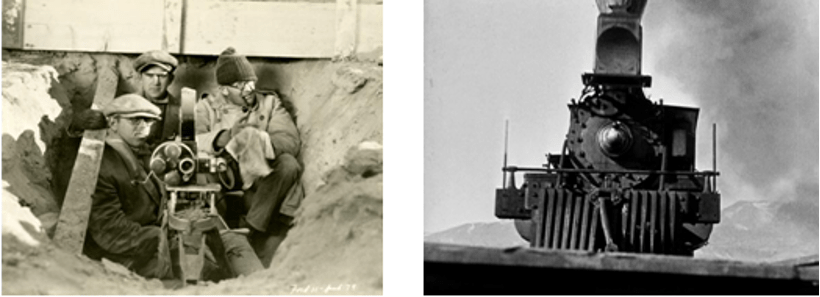

When Ford came to direct The Iron Horse (1924) for Fox, Westerns were still relatively popular with cinema audiences. Both the director and studio capitalized on the public’s interest in the super-Western; James Cruze had scored a huge box-office hit the previous year with The Covered Wagon (1923), an epic tale of early Western pioneers complete with cattle stampedes, Indian attacks and the struggle against the elements. [1] Ford’s film was just as epic; a love story set against the building of the railroad across America, featuring some of the same set pieces that made The Covered Wagon (1923) such a popular film. It also turned out to be Ford’s most successful silent title, costing approximately $280,000 to produce and returning in excess of $2 million at the box office (Gallagher, 1988, p.32). Two years later, Ford and Fox attempted to repeat the success of The Iron Horse (1924) with another big-scale Western, 3 Bad Men (1926). The film again centred on a love story played out against a background of real events, in this instance the Dakota land rush of the 1870s. Unfortunately, the film did not repeat the level of success enjoyed by The Iron Horse (1924), despite the contention by some film writers and scholars that out of the two, 3 Bad Men (1926) is the better film. McBride claims that it ‘gracefully blends the epic with the intimate […], pointing most clearly to the strengths of his mature masterpieces’ (McBride, 2003, p.155). Scott Eyman maintains that, although ‘the characterizations of Three Bad Men seem stock […], the story is stronger than that of the earlier film and gains stature by being dramatized against the opening of the West’ (Eyman, 1999, p.95).[2]

3 Bad Men (1926) is closer in style to Ford’s later Westerns than The Iron Horse (1924). Whilst the protagonists of the title are the natural descendants of Carey’s Cheyenne Harry, they also provide the template for the more complex characters that inhabit Ford’s sound films, Ethan Edwards in particular. Although clichéd and stereotypical at times, Bull, Spade and Mike are more memorably drawn than the main figures in The Iron Horse (1924). Similar in a number of ways to the fate of the outlaw gang in Sam Peckinpah’s film The Wild Bunch (1969), and in keeping with the occasional Fordian theme of self-sacrifice, they accept they are men out of synchronisation with progress, and their deaths in some small way contribute towards the continued existence of family and community. The critical and commercial failure of Ford’s 3 Bad Men (1926) [3] meant that Ford would not direct another Western until Stagecoach (1939)[4], a film that would help to re-establish the popularity of the form with both the studios and the cinema-going public.[5]

Operating within the studio system, Ford was compelled to work on the films of other directors in the subordinate role of first or second assistant director, ‘a common practise in the days of the studio assembly-line system’ (McBride, 2003, p.154).

On one such film, Nero (J. Gordon Edwards, 1922) (Fig. 6.1), presumed lost, the studio demanded a more dramatic ending, and passed the job on to Ford. He in turn ‘proposed slightly more than a week of retakes to turn the climax of the film into as close a simulation of a patented Griffithian ride to the rescue as possible’ (Eyman, 1999, p.75).[6] The reference to Griffith implies that Ford still invoked the early influences that shaped his own style. The climax ofFord’s North of Hudson Bay

(1923), for example (Fig. 6.2), is similar to Griffith’s earlier Way Down East (1920) (Fig. 6.3). Both films feature their respective heroines fighting against the raw power of a raging river. The comparison is even more obvious with the presence of frozen ice to add to the peril, illustrating that Griffith’s influence on Ford was still obvious towards the mid-1920s. Ford also worked as 2nd unit director on both What Price Glory? (Raoul Walsh, 1926) and Seventh Heaven (Frank Borzage, 1927), films covered in more detail in the following chapter.

The success of The Iron Horse (1924) meant that, ‘after 10 active years, […] his name became known outside the industry’ (Wooton, 1948, p.13). Eyman and Duncan state that ‘the New York Times didn’t review a single Ford film before 1922, and even after that ignored some of his pictures’ (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.37). Joseph McBride suggests that the fame bestowed upon Ford after the box-office popularity of The Iron Horse (1924) was comparable to the celebrity associated with Steven Spielberg upon the release of Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) (Interview with the author, 19/10/07). At this juncture in the career of both directors, it should be noted that whilst Ford had already directed nearly fifty films prior to The Iron Horse (1924), Spielberg had only one previous full-length feature film, The Sugarland Express (1974), to his name. [7]

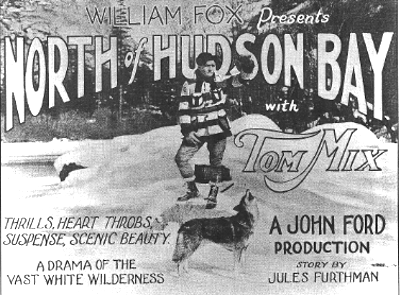

Ford’s profile was suitably heightened after this point, as various articles and promotional materials prominently featured his name and image. In fact, a year before the release of The Iron Horse (1924), the name ‘John Ford’ appears in bold upper case letters on a lobby card for North of Hudson Bay (1923), the type and size of the text the third largest on the image after that of the producer, William Fox, and the star

of the film, Tom Mix (Fig. 6.4). The journey from the individual John Ford to the brand ‘John Ford’ had started.

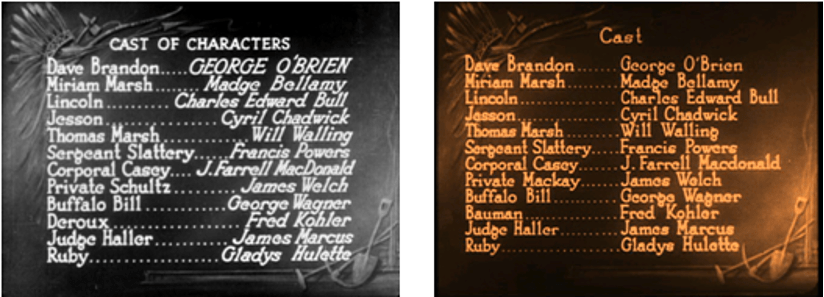

Ford took the method of working with a stock company at Universal to his new studio. His company of leading actors at the Fox Corporation included stars such as Tom Mix and John Gilbert, but, during the 1920s, the director worked with George O’Brien more than any other leading man. Like John Wayne, who effectively became an ‘A’ list star after appearing in Stagecoach (1939), [8] O’Brien was himself propelled into the limelight after the success of The Iron Horse (1924). The Fordian protagonist, as played by O’Brien, tended towards the uncomplicated, both morally and psychologically. This was in direct contrast to the on-screen persona and acting style of Harry Carey. Whereas Carey brought elements of his own personality to Cheyenne Harry, O’Brien depended more upon his looks and physique to convey character.

Possibly due to the ineffectiveness of O’Brien as a leading man, the narrative in a number of Ford’s Fox titles began to focus as much on the secondary characters as it did on the main protagonist. The ‘romantic lead’, as played by someone like O’Brien, is relegated to a subsidiary role whilst the supporting characters in effect become the real ‘stars’ of the film. For example, the three sergeants who feature in The Iron Horse (1924) are just as memorable as O’Brien, who plays the lead. By the time Ford comes to direct O’Brien in 3 Bad Men (1926), the title itself says it all. He may be the purported lead, but the film is most definitively concentrated upon the trio of outlaws who embody and preserve the nature of the ‘good bad man’, as epitomised earlier by Carey, whilst the love story between O’Brien and Madge Bellamy takes second place to the redemption of Bull, Mike and Spade.

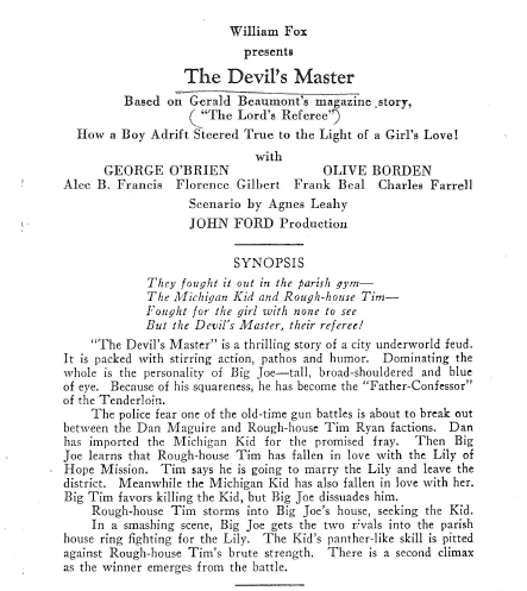

Fox continued to pair Ford and O’Brien throughout the 1920s; the duo worked together on another four silent films: Hearts of Oak (1924), The Fighting Heart (1925), 3 Bad Men (1926) and The Blue Eagle (1926).[9] The studio also proudly

publicised a further collaboration, The Devil’s Master (Fig. 6.5), a title that for some reason was never actually produced, although certain elements of the synopsis appear to have made their way into the scenario of The Blue Eagle (1926).

One of the major differences between Ford’s Universal work and the titles he made at Fox is that his films started to

feature women in the lead roles, beginning with ShirleyMason in both Jackie (1921) (Fig. 6.6) and Little Miss Smiles (1922) (Fig. 6.7). There appears to be no instance of Ford working on a film featuring a main female lead up to this point. The Shirley Mason titles herald the beginning of Ford’s occasional penchant for placing women at the heart of the narrative, pre-figuring later Fox productions The Shamrock Handicap (1926), Upstream (1927), Four Sons (1928) and Mother Machree (1928), starring Janet Gaynor, Nancy Nash, Belle Bennett and Margaret Mann respectively.[10]

Although he rarely used the same actress more than once, the introduction of a strong female character in these early films is the genesis for the staunch matriarchal figures that eventually take up almost full-time residence in the director’s work. The effect of collaborating with various actors and actresses from one film to the next means that Ford’s Fox titles lack the essence of continuity which distinguish the films he directed for Universal – though there is still a sense of audience familiarity engendered by the appearance of known faces such as J. Farrell McDonald and, to a lesser extent, George O’Brien. The variety of Ford’s work at Fox in terms of genre, however, means that these films can be viewed as specific entities in their own right, rather than, as with a number of his Universal titles, a continuance of the film that came before.

The motif of the outsider as a man of action also accompanies Ford in his move from Universal to Fox, but is only foregrounded in the narrative on an intermittent basis in his silent Fox films. For example, Bim, the hero of his first Fox film, Just Pals (1920), whilst almost certainly an outsider in his own community, is more a man of indolence

rather than one of action (Fig. 6.8). Unlike the slow-burning then quick-to-action screen persona of Cheyenne Harry, Bim is only moved to a state of activity once his own life is threatened by a lynching. The slow pace of Just Pals indicates Ford’s willingness to methodically chart the evolution of a character from inaction to heroism, rather than to jump straight away into the non-stop frenetic action that typifies his Universal films.

The minor theme of an older figure mentoring and befriending a younger person manifests itself for the first time in the extant films in Just Pals (1920). The relationship between Bim and the young Bill is a precursor to other elder / younger teams such as the two brothers in both The Blue Eagle (1926) and The Brat (1931), as well as later examples including John Wayne and John Agar in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Spencer Tracy and Jeffrey Hunter in The Last Hurrah (1959).

In both Three Jumps Ahead (1923) and North of Hudson Bay (1923), the cowboy star Tom Mix cannot be identified as anything other than a man of action, and an outsider, particularly in the latter title. In The Iron Horse (1924), however, it is difficult to identify one specific character as a definitive outsider. It could be argued that this role falls to the ethnic minorities portrayed in the film, such as the Italians and Irish who personify those who operate on the borders of mainstream society. Their efforts in helping to build the trans-continental railroad are proof enough that, even though they belong to a minority group, they have as much right to become members of the community as any other pioneer or settler. Whilst the subject of ethnicity will be considered in more detail later in this chapter, it is worth observing that characters such as the Irish labourer Casey, and his Italian workmate Tony, are also capable of springing to the defence of other ethnic groups when required. As outsiders and men of action, they represent further additions to a long line of Fordian figures who earn their place in society through deeds, not words.

In 3 Bad Men (1926), the obvious outsider appears initially to be the character of Dan O’Malley – played by George O’Brien – a young cowboy of Irish birth, who arrives in America to start a new life. The dubious background of Bull, Mike and Spade, the eponymous trio at the centre of the narrative, emphasises the innocent nature of O’Malley, who, although not exactly a man of action, is immediately accepted by the community. As the narrative unfurls, it becomes obvious that Bull and his companions are actually the real outsiders and men of action. The nature of the ‘good bad man’ as outsider and man of action has progressed from its earlier incarnation, as personified by Cheyenne Harry, a character whose motives are frequently associated with a wish to join the social group. Instead, the three bad men of the title steadfastly refuse to abandon the lawlessness that separates them from everyone else, only gaining acceptance by the community through an act of self-sacrifice.

The type of all-action film Ford was required to deliver at Universal is consigned to only a handful of the twenty titles he made at Fox from 1920 to 1926, and restricted mainly to those with a Western theme. The effect on the director’s approach to his craft was the abandonment of the early ‘guerrilla’ style of filmmaking he had employed when working with Harry Carey, in which they would ride off into the Californian hills with a cameraman and a group of actors and film the story almost off the cuff. Fox therefore gave Ford the opportunity to leave the conveyor-belt approach of turning out ‘oaters’ literally on a month-by-month basis and to take his time in developing a more professional approach to his craft.

Autobiographical Influences

Ford continued to extol the virtues of family, along with the associated sub-themes of fragmentation of the family group and the power of the matriarch, throughout the majority of films he made for Fox in the 1920s. The theme of mother-love also begins to surface in his work, accompanied by further reference to group ritual as well.

Whilst hardly discernible as a primary motif in Ford’s Universal films, the theme of Irishness eventually begins to establish itself in the director’s mid-1920s work. Louis Marcorelles asserts that ‘Ireland […] is the heart of his work and his mentality’ (Marcorelles, 1993, p.71). The fact is, however, that John Ford was not born in Ireland. As McBride recounts, ‘the town records of Cape Elizabeth, Maine, indicate that Ford was born John Martin Feeney at home on February 1, 1894’ (McBride, 2003, p.21). He sometimes encouraged the suggestion that he actually hailed from the ‘Old Country’, and his Irish films helped to perpetuate the myth of the director who left Ireland to make good in America. The point that Ford’s depiction of the Irish was stereotypical, inevitably comical, and at times quite defamatory, should not detract from the argument that the Irishness in his work is linked to his own background. Lourdeaux points out that, ‘like many non-intellectual Irish Americans, religion in his life was a great unexamined force’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, p.90). Ford’s Catholic upbringing unites the twin themes of Irishness and religion, and during this period the director’s films began to feature religious – although not uniquely Catholic – symbolism and iconography.

The Family Unit

The foundation of a communal society rests on the concept of the family unit, and Ford’s family were most certainly integral to the community in Portland, Maine, where his father, John Feeney, owned a saloon. Along with tending bar in his own establishment, Feeney was also a point of contact for new Irish immigrants arriving in America. As Dan Ford writes, ‘when an Irishman stepped off the boat, John Feeney helped get him a job on the docks, and saw that he had a bucket of coal on a cold day, and a free beer on a hot one’ (Ford, 1998, p.4). Joseph McBride also records that Feeney would ‘help them fill out their citizenship papers, and instruct them how to vote’ (McBride, 2003, p.34).

As stated earlier, Ford’s family eventually fragments and fractures, and the start of this process was initiated by the defection of his older brother, Frank, to Hollywood in 1905. The incomplete family unit is referenced in The Iron Horse (1924), in which, at the beginning of the narrative, the father is already a widower, left to raise a young son. This fragment of family is reduced even further through the murder of the father. The tenuous nature of family is also indicated by a couple who marry then separate in a matter of hours, the rigours and hardship of building a railroad clearly not conducive to stable relationships. In fact, it is only once the railroad is finished, an event described in a title card as ‘the wedding of the rails’, that the main characters can unite in marriage and, by

implication, establish a family of their own (Fig. 6.9).

The underlying theme in 3 Bad Men (1926) concerns the foundation of family made possible through an act of self-sacrifice by those outside of mainstream society. Thebenign outsider, Dan O’Malley, is able to attain the goal of

domesticity (Fig. 6.10) only through the actions of the three outlaws, who themselves vicariously embrace the ideology of family through O’Malley before giving their lives for the good of the community. The sacrificial death of the three outlaws contributes towards the creation and continuance of family, a thematic motif that Ford would employ again in later films such as 3 Godfathers (1948), and 7 Women (1966).

Ford’s interest in the family is not confined just to the permutations of father and daughter, mother and son, and husband and wife. The theme of sibling love can be found in 3 Bad Men (1926), The Blue Eagle (1926) and Hangman’s House (1928). In the first two titles, brothers attempt to rescue a younger family member from falling in with the criminal element, in a failed attempt to keep the family unit together. As with the character of Citizen Hogan in Hangman’s House (1928), the chief protagonists then seek vengeance on those responsible for the fragmentation of family.

When Ford does attempt to portray a complete family group, there is inevitably a schism caused by outside events. In Lightnin’ (1925), it is the imminent arrival of the railroad that threatens the relationship between husband and wife; a pair of swindlers turns the couple on each other as they persuade the wife to sell the family home. The power of the matriarchal figure over the husband is established early on when Bill Jones refers to his wife as ‘mother’, the deference to his wife perhaps mirroring the kind of relationship Ford witnessed between his own mother and father. McBride confirms this state of affairs in the Ford household, stating that Ford’s father ‘knew his place at home. He was content to leave the family finances and most of the parental discipline to the […] “woman of the house”’ (McBride, 2003, p.44). Only when their marriage is under threat does Bill Jones take on the swindlers

in court, winning his wife back in the process (Fig. 6.11).

As early as 1922, Ford’s involvement with the mother-love genre in his silent Fox films becomes more pronounced. For instance, although the film is presumed lost, it is obvious from some of the existing materials for Silver Wings (Edwin Carew and Jack Ford, 1922) that the mother figure is the main focus of the film. The poster accentuates the notion of mother-love by framing the image of the star of the film, Mary Carr, with a heart-shaped border (Fig. 6.12).

As Eyman and Duncan point out, although Ford only ‘directed the prologue, which contains an emotional scene where the baby dies’ (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.45), a still from the film emphasizes the mother-son relationship that Ford would employ in a number of his later Fox films (Fig. 6.13).[11]

Another example of a mother and son relationship can be found in North of Hudson Bay (1923), a melodrama set in the snowy wilderness of North America, and the second film Ford made for Fox with the cowboy star Tom Mix. As with Silver Wings (1922), the closeness of matriarch and son is defined by a physical intimacy that borders on the

Oedipal, an aspect ofthe form that may account for its ultimate demise as a mainstream Hollywood genre (Fig.6.14). As discussed in the following chapter, it would not be until Ford came to direct Four Sons (1928) and Mother Machree(1928) in the late 1920s that his work in this genre would evolve to the point where the main impetus of the narrative totally focuses upon the theme of mother-love.

Ritual

Ford continues to seamlessly integrate the rituals of eating and drinking throughout his early Fox work, although, based on the surviving films from this period, there is nothing to suggest that the presentation of these themes has progressed or evolved significantly from the director’s Universal period. In The Iron Horse (1924) and 3 Bad Men (1926), however, dancing becomes more prevalent within the narrative, underlining the role that this ritual plays in the establishment of community. Ford first appears to indicate an interest in the formal rigidity of dancing, albeit fleetingly, in The Iron Horse (1924); the image is in deep focus so that the dancers in the background are

emphasised as much as the foreground action (Fig. 6.15). A year or so later, with The Shamrock Handicap (1926), Ford introduces, for the first time in his extant silent

films, the visual motif of formal dancing within a civilised community (Fig. 6.16). When hunting for suitable husband

material for Lee Carlton, the young girl they have adopted after the death of her father, two of the 3 Bad Men (1926) (Fig. 6.17) instinctively head for the nearest saloon, in which the presence of dancing couples emphasises yet again the ritual of the dance as an act of communal bonding. Other social rituals that occasionally figure in Ford’s silent work include the ceremonial aspects of the law and marriage. The former can be found in The Iron

Horse (1924) (Fig.6.18), where the imposition of order upon society is exemplified by the pretext of the ‘lawful’ trial, a motif that Ford returned to a number of times in his work. There is a suggestion of an underlying cynicism on Ford’s part when considering the need for one individual to cast judgement on another, with the ‘judge’ portrayed as a self-appointed arbiter of casual justice, as well as overseeing weddings and divorces. This disdain for authority

carries over into Lightnin’ (1925), in which the judge is shown as a figure of fun, not to be taken seriously (Fig. 6.19).

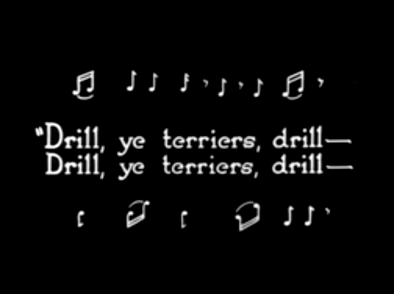

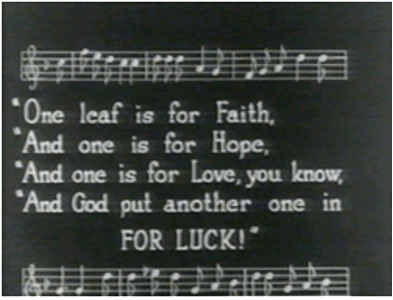

Music as a form of ritual now starts to appear more frequently in the director’s Fox films. Although the presence of diegetic traditional music and song in film is of course not unique to Ford, the manner in which he uses music to comment upon community and the personality of his protagonists is distinctly ‘Fordian’. Kalinak emphasises this trait, stating that, to Ford, music serves ‘as a window into both character and theme’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.48). For example, in The Iron Horse (1924), Ford employs traditional folk music to emphasise the ethnicity of his characters, as the Irish railway workers

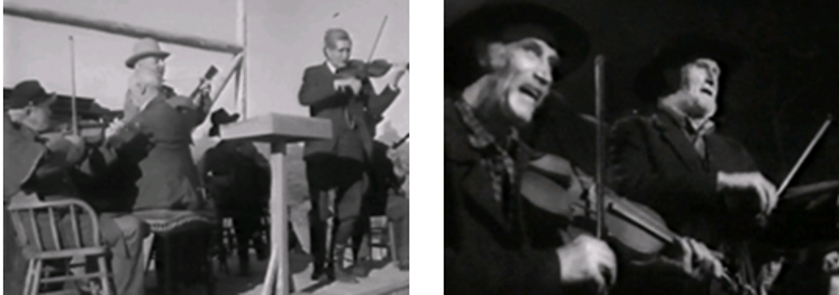

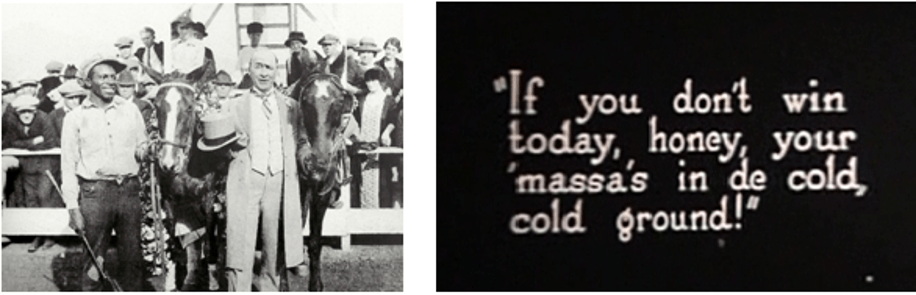

hammer away to the tune of ‘Drill Ye Terriers Drill’ [12] (Fig. 6.20). Kalinak points out that the lyrics ‘encapsulate the film’s theme of cooperation and assimilation and whose rhythms force the men to work together’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.15). In 3 Bad Men (1926), Dan O’Malley is introduced via his singing of ‘All the Way from Ireland’ (Figs.

6.21 & 6.22), the earliest, but certainly not the last, of Ford’s characters to be defined through music. According to Kalinak, ‘the song is an adaptation of a rather obscure Irish ballad […] about a young Irish girl [for whom the] lyrics were rewritten to accommodate the narrative of the film, and I think it quite likely that Ford rewrote them himself’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.48).

The evolution of this motif progresses from the early silent films to the point where, as Kalinak points out, song contributes ‘to narrative trajectory, character development, and thematic exposition’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.2). Kalinak suggests that the use of traditional folk music in Ford’s Westerns, whether it is diegetic or part of the score, lends ‘verisimilitude to the images on the screen’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.106), the numerous genuine folk songs and authentic hymns making ‘the film’s representation of the West seem authentic’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.106). Whilst this is a salient point, it could be argued that Ford’s musical choices mask an even more authentic agenda for the settlers, namely the appropriation of land from its previous inhabitants. Indeed, hymns such as ‘Shall We Gather at the River’, ‘Bringing in the Sheaves’ and ‘Silent Night’, as featured in a number of Ford’s later sound films, seek to reinforce and impose a sense of righteousness upon the pioneers as they blithely take what is not theirs, in the name of their God.

Another example of the theme of communal bonding through song can also be found in The Iron Horse (1924) (Fig.

6.23); the labourers and their female companions perform a musical number on an open top wagon as the train travels to the end of the line in preparation for the construction of the next section. The nature of the musicians changes temporarily from amigratory community to a cohesive social group through the celebration of song. The labourers find affinity of purpose through music, and specifically through songs representative of their own experience, namely as builders of railways. They then revert to their primary roles, as temporary workmen and morally compromised entertainers, once the train reaches its destination.

Not all of the songs or music featured in the early Ford films can be categorised as traditional, but a number of the remaining silent films contain at least one musical sequence or reference to song. As mentioned earlier, 3 Bad Men (1926) features the Irish cowboy Dan O’Malley singing of his love for Ireland as he travels across the Western landscape. The narrative of The Shamrock Handicap (1926) portrays this situation in reverse, the return of the failed jockey Neil Ross to Ireland accompanied by

what appears to be a non-diegetic song in celebration of his homecoming (Fig. 6.24).

In the later sound films, Ford’s passion for traditional music manifests itself in his first sound Western, Stagecoach(1939), featuring a non-diegetic medley of American folk songs to accompany the main characters in the film. Kalinak states that the song ‘Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair’ serves as a ‘leitmotif for the Southerners, Mrs Mallory and Hatfield’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.59) whilst the characters of Dallas and Ringo are ‘validated as a couple’ through the use of a song entitled ‘I Love You’, a popular love song from the 1920s. Ford also uses folk music to signify that most enduring iconographic image of the Western, a stagecoach, the vehicle seen either entering or leaving town to the strains of the traditional cowboy song ‘Oh, Bury me Not on the Lone Prairie’. This particular association of icon and traditional music is used in a number of Ford’s other Westerns, notably 3 Godfathers (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Two Rode Together (1961), the repeated marriage of image and music serving as a filmic shorthand to communicate the exhilaration of travelling across the wide open spaces of the West.

Ford uses diegetic music to show commonality of purpose within the community, whether through music provided by a group, as shown in My Darling Clementine

(1946) (Fig. 6.25) and Wagon Master (1950) (Fig. 6.26), the serenading of one group

to another in Fort Apache (1948) (Fig. 6.27), or the serenading of one individual by another, as in The Searchers (1956) (Fig. 6.28). Diegetic music is also employed when referencing the loneliness of military life. In both Fort Apache (1948) and Rio Grande (1950), the officers and their wives and partners are entertained by the lower ranks who serenade them with songs such as ‘Sweet Genevieve’ and ‘I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen’. This last song, as featured in Rio Grande (1950), is an apparent reference to Kathleen, the estranged wife of Kirby Yorke.

As presented in Fort Apache (1948), the fact that the songs are delivered either as an all-male group offering or by a single male does not detract from the traditional

masculinity of the singer (Figs. 6.29 & 6.30). Although Kalinak points out that ‘male performances of song and dance are manifestations of femininity in Ford’, she maintains that ‘in his Westerns, the embrace of the feminine is not a negative attribute’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.138). To Ford, singing is a natural emotional outlet for his male figures, irrespective of their role either as singer or audience.

Ford all but abandons his love of traditional music towards the end of his career, with films such as Sergeant Rutledge(1960) and Two Rode Together (1961) practically devoid of any allusion to traditional folk music. Both films are reliant on original scores by Howard Jackson and George Duning respectively. [13] Two Rode Together (1961) is an exception to other Ford Westerns in its use of a number of Strauss waltzes in the ubiquitous dance sequence, and a piece by Boccherini, emphasising Ford’s lack of interest in the material as a whole [14].

Another effect engendered by traditional music is nostalgia, reinforcing the almost palpable mood of loss and mourning that pervades most of the director’s films. Ford encourages this by referring to themes he has used before, recycling ‘Martha’s Theme’ for example from The Searchers (1956). Ford was so enamoured of the music – based on a Civil War era song entitled ‘Lorena’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.164) – he used it again as a love theme in The Horse Soldiers (1959). [15] Despite Ford’s protestations that ‘generally I hate music in pictures’ (in Bogdanovich, 1978, p.99), a Ford Western would not be complete without traditional music, folk or otherwise, to accompany the settling of the West.

Eyman and Duncan categorise the twin rituals of music and dancing under the heading of visual motifs (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.16), although it could be argued that these rituals are also thematic as well. Kathryn Kalinak quotes Peter Stowell’s contention that the dance scene in My Darling Clementine (1946) is ‘Ford’s ultimate

expression of community cohesion […] sealing civilisation’s compact’ (Kalinak, 2001, p.174) (Fig. 6.31). As a thematic element of the narrative it also celebrates the acceptance by the community of their new sheriff, an individual associated with the more brutal aspects of frontier life. Conversely, it also signifies Earp’s own acceptance of community and the surrendering of his individuality in order to be a part of the very group he is paid to protect. He is, in that moment, no longer an outsider in his own town.

The dancing in The Searchers (1956) (Fig. 6.32) again underlines the theme of communal unity but also indicates how the community has moved on from the brutality visited upon the family five years earlier. The arrival of Ethan and his brother’s adopted son, Martin Pawley, halfway through the subsequent marriage ceremony, is a reminder that singing and dancing can only temporarily shield the settlers from the violence that constantly surrounds them. [16] Occasionally, Ford will insert a dancing sequence as a purely celebratory event, with no subtext for its inclusion other than to show people enjoying themselves for the sake of it. Both The Grapes of Wrath (1940) and Wagon Master (1950) have these scenes in common, the latter containing elements of the dancing episode in the credits as a celebration of pioneer life.

Ford’s Westerns also offer a number of examples of military precision dancing, the formal and rigidly staged mise-en-scène in direct contrast to the less disciplined approach Ford takes towards the non-military community events. The mannered etiquette of the military is obviously reflected in the way the officers and their partners comport themselves when dancing; the dancing in Fort Apache (1948) almost mimics the soldiers who march and ride in close column as they both enter and leave the fort

(Fig. 6.33).

The insularity of the dance ritual, whether military or performed by settlers and pioneers, also functions to exclude outsiders. In both Wagon Master (1950) and Two Rode Together (1961), the ceremony of dancing is cut short by people who attempt to disrupt the harmony of the ritual, or who do not fit in acceptable society. The Clegg gang impose themselves on the settlers in Wagon Master (1950), terminating the celebrations with their menacing

presence. In Two Rode Together (1961), Elena de la (Fig. 6.34) has been rescued from years of captivity as the wife of a Comanche warrior chief. The result is exclusion from the dance ceremony by the community members.

One other ritual that Ford continues to allude to in the films he directs at his new studio is the theme of ceremonial burial, most notably in The Iron Horse (1924). A nameless

woman grieves for her dead partner (Fig. 6.35), with the gravediggers hurriedly filling in the burial site as the rest of the townspeople depart for a new location to continue the building of the railroad.

An adjunct to the ceremony of funeral that Ford revisits numerous times in his later films is conversing with the dead. There is an early example to be found in The Scarlet

Drop (1918) (Fig. 6.36), in which Harry Ridge, returning from fighting in the Civil War, discovers that his mother has died in his absence. He stands by her graveside and caresses the cross, trying to make a connection to his dead mother.

The ritual of burial is a significant feature of Ford’s later films, and the funeral sequences occasionally expose a separate and secondary enigma touched upon in

the narrative. For example, in She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949) (Fig. 6.37), the Union Army captain, Nathan Brittles, allows former members of the Confederate army in his troop to honour the death of their Civil War general by draping his coffin with a Confederate rebel flag. This gesture by Brittles underlines the healing of the wounds suffered by both sides in the Civil War and also reinforces the need to bind the community together.

The interruption of the funeral service by Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956) reinforces Ethan’s blind hatred for the Comanche war party that has caused the

disintegration of the only family to which he had close ties (Fig. 6.38). It also reveals his contempt for formality and ritual in the face of a wilderness still untamed, and his disregard for religion; Ethan has forsaken God a long time ago. His disrespect for the departed encompasses Native Americans as well, when he shoots the eyes from a dead Comanche warrior with the justification that without them ‘he can’t enter the spirit land, and has to wander forever between the wind’.

The funeral scene in 3 Godfathers (1948) is more religious in tone, the film itself a parable of the story of the birth of Christ with the main characters as the three wise men. As Place pointsout, the burial ceremony ‘is the first step in their religious initiation’, further noting that the funeral is filmed ‘in long shot, a composition that

intensifies the ritual’ (Place, 1973, p.95)(Fig. 6.39). As in The Searchers (1956), the burial of the dead is accompanied by the singing of ‘Shall We Gather at the River’. In this instance however, the hymn is concluded without interruption. The death of the mother is accepted as an act of God.

Ford does not restrict the depiction of funerals as an indicator of white society alone. For example, in Sergeant Rutledge (1960), a troop of African American cavalry

soldiers bury one of their fallen comrades in the middle of the desert (Fig. 6.40). One of the soldiers bemoans the fact that they cannot give their colleague a proper military funeral. Rutledge insists that they are still going to ‘do it upright for him… we’re going to wait for the lieutenant to read the words over him’. Rutledge’s deference to hierarchy – their commander is a white man – indicates a need for the ritual to be performed in adherence with white values, validating the death of the black soldier as an act that benefits the community as a whole, without regard for colour or ethnicity.

In foregrounding the plight of the Native American in Cheyenne Autumn (1964), Ford accords his characters the privilege of a full funeral ritual for the first time in his work. If the burial of the dead is indicative of civilisation, then the funeral of the Cheyenne

chief (Fig. 6.41) implies that, culturally, Native Americans share the values and ceremony of the white settlers. The continued reference to ritual in Ford’s work became, in Bordwell and Thompson’s words, one of the ‘stylistic patterns’ that audiences would learn to interpret as ‘the filmmaker’s personal comment on the action’ (Bordwell and Thompson, 1994, p.416).

Irishness

In a remarkably short space of time, Ford investigated the role of the Irish within and outside American society, from cursory comedic sidekick, through to the part they played as builders of a nation, settlers of the West, and eventual figures of authority. In the 1920s alone, the director made half a dozen films that dealt specifically either with Ireland or the Irish, including titles such as The Shamrock Handicap (1926), Mother Machree (1928) and Hangman’s House (1928). In doing so, he played a large part in the creation of the archetypal blustering cinematic Irishman.

It would appear that Ford’s first reference to Irishness is with the late Universal title, The Prince of Avenue A(1920), a political melodrama featuring the famous heavyweight boxing champion, James J. Corbett. According to a review at the time of its release, ‘even the old Irishman leader in his shirt sleeves and plug hat is true to type’ (Review by Marion Russell, 1920, Lilly Library Collection, Indiana University). The ‘true to type’ Irish stereotypes of the 1920s are variously described as ‘amiable drunks and aggressive brawlers, corrupt politicos and honest but dumb cops, Catholic priests and angelic nuns, long-suffering mothers, feisty colleens, and vulnerable, naïve maidens’ (Anon, ‘Cinema and the Irish Diaspora’, 2010).

Ford’s first real Irish character of note in the extant Fox films appears in The Iron Horse (1924). Corporal Casey is a God-fearing Catholic; his rosary beads always near at

hand during times of crisis (Fig. 6.42). A title card gives a contemporary flavour of the archetypal Irish character as typified by Hollywood at the time, as Casey is given to make a speech with the words, ‘Twas me illigant Irish iloquence that did it – was it not?’, the stereotype compounded when Casey becomes embroiled in a bar room brawl.

Although The Iron Horse (1924) features a number of other ethnic groups, it is Casey who takes centre stage in terms of the non-American characters. Ford’s empathy is obviously with the Irish character, privileging Casey as a confidant of the main protagonist, a young American engineer, Davy Brandon (George O’Brien). Both actors are paired together again a few years later in 3 Bad Men (1926). This time though, it is O’Brien, as Dan O’Malley, who is of Irish origin, displaying the qualities of bravado and bluster that define so many of the Irish figures in Ford’s later films. A title card declares on behalf of O’Malley, concerning the race for land that marks the climax of the film, that ‘you’ll be needin’ speed that day! And wings – – an’ th’ Irish have em’. Not content with representing his own countrymen literally as the physical builders of the nation, as with Casey in The Iron Horse (1924), Ford now also lays claim to the Irish as pioneers of the West. O’Malley settles down to family life by the end of the film, and, in the process, tames the land as well.

A

The Shamrock Handicap (1926) is the second entry in the short-lived horse racing genre that Ford directed for Fox, along with the earlier Kentucky Pride (1925). This is the first known Ford film in which part of the story actually takes place in Ireland, in the process becoming associated with a genre that would appear, in the 1920s at least, to be specific to him alone; the Irish film. [17] Ford’s depiction of his parents’ homeland is inevitably viewed through rose-tinted film stock, the countryside populated with

dancing villagers and laughing shepherd boys (Fig. 6.43). Lourdeaux attributes the Irish-American love for the Old Country to ‘a strong sense of displacement [through which] the Irish in America acquired an intensely nostalgic view of their heritage in general and of pastoral scenes in particular – and horses’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, pp.98-99).

There is a detectable air of underlying cynicism in this film towards the idea of the American dream. For example, one of the main characters, Neil Ross, fails in his ambition to become a champion jockey in the new country. The mise-en-scène also betrays uncertainty towards the notion of America as a land in which all dreams are fulfilled. The idyllic countryside of Ireland is represented as a Garden of Eden, with Neil and the girl he loves framed beneath the protective umbrella of a heavily branched

tree (Fig. 6.44). In contrast, Ford presents America as a fake paradise. The image of the cottage surrounded by a white picket fence –cinematic short-hand for middle America – is subverted by framing it against the background of a looming high-rise

building (Fig. 6.45).

Ford highlight’s, albeit in a comic manner, the integration of the Irish into American society by indicating in The Shamrock Handicap (1926) that every member of the police force hails from Ireland. Ultimately, however, the film suggests that an Irishman can only ever be happy back in his native country, to which Ross eventually returns. Lourdeaux proposes that the word ‘handicap’in the title of the film is also a reference ‘to the drawback of being Irish in America, where the Irish often felt unwanted’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, p.98).

The yearning for home is a major thematic pattern in many of Ford’s films, and it is perhaps indicative of the director’s own nostalgia for an environment that he never truly knew himself. Ford is in effect living vicariously through the wish-fulfilment of the characters in his work. It seems as though Ford’s Irish films allow him the opportunity to wallow in the values, traditions and rituals that define the Old Country, even though his view of Ireland at this point is based purely on a Hollywood construct.

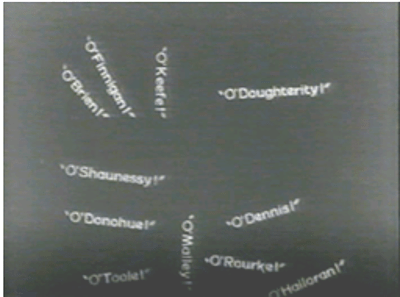

Ford has no qualms in celebrating his love for Ireland over that of his parents’ adopted country. When Ross finally makes it back to his homeland, a title card lists nearly a

dozen Irish names (Fig. 6.46), all beginning with ‘O’, as in O’Keefe or O’Brien. Ross is back where he belongs, in the land that he loves, and more importantly, with his own kind. Perhaps that is what Ford is attempting to do in so many of his Irish films, to keep company with characters with whom he has nothing in common, other than a shared communal past.

According to J.A. Place, ‘Ford never let go of his Irish heritage; indeed in his work he celebrated it’ (Place, 1979, p.148). Place also states that Ford’s films catered to ‘the traditions associated with the Irish’ (Place, 1979, p.149), a point emphasised by the numerous Irish characters that populated the director’s later sound films. The care the director takes to promote the detail of Irish ritual and heritage helps define the ethnicity of later Irish figures such as Martin Maher in The Long Gray Line (1955) and Frank Skeffington in The Last Hurrah (1958). However, observance of Irish ritual appears to be almost totally absent in his early Fox work, suggesting that Ford’s attitude towards his own ethnicity was shaped and influenced as much by the contemporary cultural concerns and generic conventions of the period, as it was by his own biographical background.

Religion

One of the mainstays of Catholicism, the need to confess one’s sins to a priest, is alluded to in a skewed manner in The Village Blacksmith (1922), in which a corrupt father and son are forced to admit their part in framing an innocent man for their own misdeeds. Ford films the confession within the confines of a church, the act of contrition on behalf of the guilty parties evoked not through the conduit of a priest during a sacrament, but by an ordinary member of the congregation. The director employs what would eventually become a signature visual motif, a three character

composition (Fig. 6.47), with the fraudulent pair arranged on either side of a character who defends the wrongly-accused. The congregation is filmed against a black

background (Fig. 6.48), with the church walls momentarily obscured as those gathered within are forced to witness a parody of the confessional played out in front of them. This reinforces the suspicion that Ford’s conflicting attitude towards his own religion is potentially related to the Catholic rituals that inevitably played a key role in his own upbringing, Ford having served ‘Mass as an altar boy at St. Dominic’s Catholic

church’ (McBride, 2003, p.56) (Fig. 6.49).

Corporal Casey’s reliance on his rosary beads in The Iron Horse (1924) indicates the beginning of a more open approach on behalf of Ford towards Catholicism in his Fox films, whereas in his Universal work there is a clear sense that the director is not totally comfortable exploring the subject onscreen. By 1924 Ford is confident enough to acknowledge openly for the first time the relationship between Irish ethnicity and ritualised religion, and to reference the personal in his professional work.

Apart from Casey and the rosary beads, and a cross on a grave mound, Ford does not broach the subject of religion at all in The Iron Horse (1924). Ford’s admiration for Abraham Lincoln, though, borders on the pious, the images of the great man shown at the beginning and the end of the film both spiritual and reverent in equal degrees. The

fact that Ford shows Lincoln in the form of a statue (Fig. 6.50), rather than a real person, as depicted throughout the rest of the film (Fig. 6.51), elevates him from the status of mere mortal to holy entity.

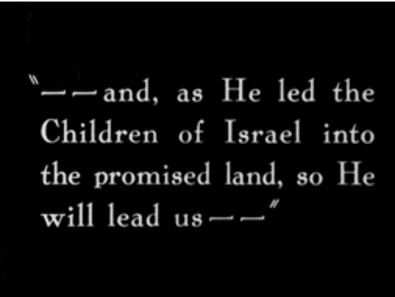

Apropos 3 Bad Men (1926), the whole film could be viewed as a religious parable of the West, with Biblical references to Moses and the Promised Land scattered throughout. The outlaws are initially glimpsed in silhouette posed against the background of a rising sun, suggesting that the trio may turn out to be three wise men, rather than three bad men. This image pre-empts the final shot of the film in which the now deceased outlaws join hands to form the shape of a cross, the trio portrayed

literally as ghost-riders in the sky (Figs. 6.52 & 6.53).

The more traditional representation of holiness can be found in the figure of Reverend Benson. He is first shown gathering water from a trough, surrounded by a group of

morally corrupt women in obvious need of redemption (Fig. 6.54). Upon seeing a ploughshare, Benson exhorts a higher force to ‘bless these plows – that they may make this wilderness blossom with the glory of God’. On closer examination, the religious aspects of 3 Bad Men (1926) appear to be more aligned with that of the Old Testament, rather than the Gospels of the New Testament. The nature of the Reverend equates more to Moses than Jesus, a comparison reinforced with a title card referring

to the children of Israel and the Promised Land (Fig. 6.55).

The name of Moses is also invoked in the famous land-rush sequence, during which unwitting parents leave a young child in the path of a charging mass of settlers, intent

on staking a claim to the wilderness (Figs. 6.56 and 6.57). [18]In 3 Bad Men (1926), Ford reinforces a vision of the West in which the religious antimony of Heaven and Hell prevails in a morally compromised world, perfectly encapsulated by the imagery of

flaming crosses (Fig. 6.58), burning buildings, pious preachers and fallen women (Fig. 6.59).

In the earliest remaining example of the director’s Irish films, The Shamrock Handicap (1926), Ford places religious iconography within the mise-en-scène of a romanticised view of Ireland. Young peasant girls make the sign of the cross, whilst the countryside

plays host to numerous examples of the same icon (Figs. 6.60 & 6.61). Ford had visited Ireland for the first time in his life five years before in 1921, and his films tend to express a preference for an idealised version of Ireland and its relationship with religion that is somewhat at odds with the reality he must have witnessed in his first, but brief sojourn in the Old Country. [19]

Outside of the Western and Irish genres, Ford tends to promote his holy characters as father figures to the community. The plot of one of the lost silent Fox titles, Thank You (1925), revolves around an ‘abused and underpaid county-town minister’ (Harrison’s Reports, 1925, p.154). The character of the minister, played by Alec B. Francis, later to play the reverend in 3 Bad Men (1926), is impugned by two other men of the church,

but his role at the centre of the community ensures that his reputation is restored (Fig. 6.62).

Returning to the theme of the holy man as an essential element of society in The Blue Eagle (1926), Ford finally embodies the twin themes of Irishness and the representation of Catholicism in the character of Father Joe O’Regan. In this instance the chaplain is an integral part of the community, facilitating a truce between two members of his congregation by having them air their differences in the boxing ring

(Fig. 6.63). Similar to the character ofRiley the Cop (1928), Father O’Regan’s Irishness is fully assimilated into a culture far removed from his own. To Ford, the Catholic religion is now deemed to be truly Irish-American. [20]

Class

Ford’s admiration for the underdog continued unabated in the period 1920 to 1926. The common theme of the innocent, lower class loner confronted with the actions of the upwardly mobile, yet morally compromised members of the community, is repeated a number of times in these early films. For example, in Just Pals (1920), Bim, the town layabout, becomes embroiled in a financial scandal in which the school mistress, Mary Bruce, is framed by a dishonest accountant for stealing school funds. Bim’s lowly position in the town hierarchy means that, when he takes the blame on behalf of Mary, he is all too readily condemned by the townspeople. His gallant behaviour leads to him nearly being lynched, an act that underlines the intolerant

nature of a community fixated on status and class (Fig. 6.64). Bim is aware of his own position within the social group of the town, an unspoken agreement through which he knows instinctively where he is welcome and where he is not. For example, he cannot bring himself to enter the office of the corrupt accountant he knows is at the heart of the scandal; class becomes a barrier that stops Bim from pointing the finger of guilt in

the right direction (Fig. 6.65).

When Ford deals with more socially privileged figures, as in Cameo Kirby (1923) for example, his lack of empathy for them translates into a casual approach to the material. Eyman and Duncan contend that Ford directs the film, which is based upon a play co-written by Booth Tarkington, ‘on autopilot’ (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.45), and McBride suggests that the star of the film, John Gilbert, was ‘weighed down by the glacial stodginess of Cameo Kirby’ (McBride, 2003, p.145). Without the conflict of class, tension between the characters is difficult to create, and the material suffers accordingly. Eyman’s suggestion that ‘Ford would always be helpless when confronted with the conventions of stage melodrama’ (Eyman, 1999, p.76) rings true in this instance and the director fails to engage fully with the material when the main protagonists are upper class characters.

Whilst not essentially addressing issues of class, Lightnin’ (1925) does broach the subject of social status as defined through the possession, or lack of, wealth and material goods. A married couple own a hotel through which the railroad is going to run, and are targeted by swindlers intent on stealing the property. Corruption is

epitomised through the authority figure of the local sheriff (Fig. 6.66), whilst social superiority is defined by the presence of the chorus of assorted gossiping women (Fig. 6.67). The chief protagonist, Bill Jones, unlike his wife, is not concerned with material goods. The subtext implies that the accumulation of wealth is in itself a corrupting force, and, in the film, one that also threatens the relationship between the married couple.

The character of Lightnin’ Bill Jones is one in a long line of Fordian figures who are happy to function as part of the community, yet continue to inhabit the fringes of their social group. Another notable example of this character type can be found in The Searchers (1956) in which Hank Worden plays the eccentric and slightly befuddled Mose Harper.

History

Joseph McBride writes of Ford’s interest in history that, ‘When he wasn’t talking or sleeping, Ford was reading books. [He] devoured biographies and history’ (McBride, 2003, p.110). One early indicator of the director’s interest in historical events can be found in his admiration for the lost cause of the Southern Confederacy, and the esteem in which he held the defeated of the American Civil War. The director’s hometown of Portland, Maine, has a memorial dedicated to the fallen Union soldiers who hailed from that part of the country, the words on the front of the plinth

commemorating ‘their sons who died for the Union’ (Fig. 6.68). Ford, though, is attracted to the social values and rituals that differentiate the North from the South, and it is the vanquished forces of the Southern states which appear to engage his respect.

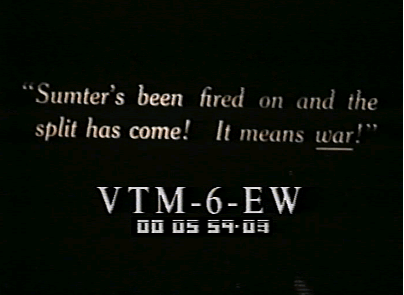

Having supposedly been involved in the production of his brother’s film, The Battle of Bull Run in 1913, it is not unexpected that the subject of the American Civil War is first broached quite early on in the director’s career. In The Scarlet Drop (1918), Harry Ridge is rejected by his socially superior Northern compatriots, compelling him to fight for the other side. The film alludes to the very beginning of the conflict, a title card

stating that war has been declared between the North and the South (Fig. 6.69), an early example of the numerous references to historical events that can be found in the director’s work.

It is probably the subject of the South itself, rather than the ‘tedious plotting’ (Eyman, 1999, p.77) of an adapted play about a Mississippi gambler, that drew Ford to the story of Cameo Kirby (1923). The opening sequence is a picture-postcard montage of

riverboats (Fig. 6.70), and banjo-strumming minstrels designed to evoke the idyllic atmosphere of the pre-Civil War South. The African Americans are stereotypical representations of slaves, with the film content to present them as nonentities, rather than fully rounded characters in their own right. Although the narrative of Lightnin’ (1925) is placed within a contemporary American setting, the story harks back to the

Civil War, and Lightnin’ Bill Jones reminisces at one point on his fallen comrades (Fig. 6.71). When his wife throws Jones out of the house, he seeks refuge in an old soldiers’

home. The familiar military rituals of flag-waving (Fig. 6.72) and marching (Fig. 6.73) provide comfort to Jones after he is banned from the marital house. It is surely no coincidence that, in 1944, Ford set up his own military shelter, the Field Photo Farm, ‘a gathering place for veterans of Ford’s [wartime photographic] unit […] as well as a refuge for members of the unit who were down on their luck or out of favour with their wives’ (McBride, 2003, p.405).

The idea of the South as the honourable face of the Civil War, and the patriotism that its cause engenders, is broached in both The Iron Horse (1924) and 3 Bad Men (1926). In the former, the three railway labourer companions, Slattery, Casey and Schultz, are ex-Confederate soldiers. They chance upon their old war-time

commander, and the three men stand to attention (Fig. 6.74), their superficial civilian manners immediately discarded once they find themselves in the company of the man under whom they previously served. In 3 Bad Men (1926), the South is embodied as a

Confederate major, complete with Southern manners and appropriate accent (Fig. 6.75). Major Carleton appears as an archetypal high ranking Civil War ex-army commander (Fig. 6.76), in the same manner that Ellen McHugh, in Mother Machree (1928), is a template for the mother figures that feature in Ford’s films.

Despite the fact that the Civil War turned Americans against each other, and that it was sixty years in the past by the time the film was made, the conflict is appropriated in The Blue Eagle (1926) to inspire patriotism in all of the fighting services. The army and the navy are united as one while they listen to the story of an old ex-Union soldier,

who fought at Gettysburg (Fig. 6.77). The numerous allusions to the South in Ford’s silent work therefore must lead to the conclusion that his sympathies were obviously more inclined towards the losing side of the Civil War. [21]

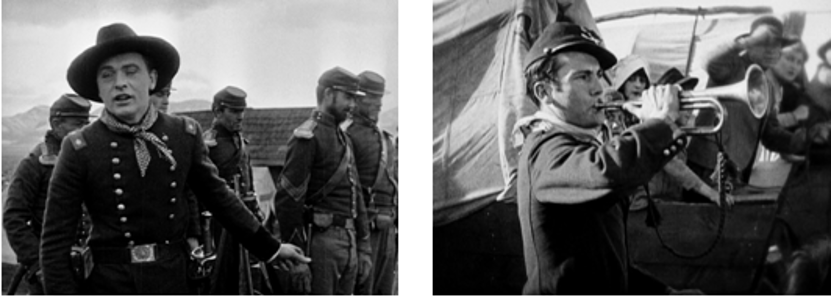

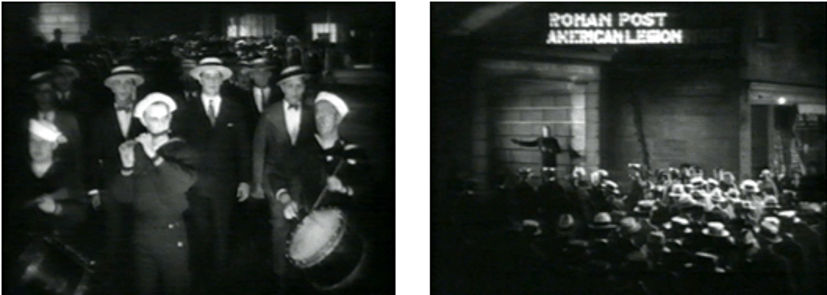

Prior to The Blue Eagle in 1926, the director refers to the military forces only in passing. Reviews of the time and narrative summaries of the other films presumed lost also do not contain any mention of the armed forces. The military have a presence in

both The Iron Horse (1924) (Fig. 6.78) and 3 Bad Men (1926) (Fig. 6.79), but are relegated mainly as background characters, nonentities like the Native American figures in the same films.

The Blue Eagle (1926) is therefore the first of Ford’s films to deal specifically with the subject of the services, in this case the Navy. The opening credits proclaim that the film is dedicated ‘to the unsung heroes of the Navy’, paving the way for an exercise in patriotism and duty to country that foreshadows later military Ford films such as Salute (1929), Submarine Patrol (1938) and They Were Expendable (1945). Although the remaining footage is missing a crucial World War I battle sequence, enough of the film survives to demonstrate Ford’s predilection for observing the rituals of military life. A

grudge boxing match between two sailors is shown as an exercise in formality (Fig. 6.80). Ceremonial burials at sea (Fig. 6.81) and marching bands (Fig. 6.82) also feature. Another marching scene towards the end of the film incorporates a secondary motif in which ex-military personnel still observe the nuances of military life, long after

having left the service (Fig. 6.83). The civilian andmilitary marchers in this sequence file into an American Legion hall at the end of the film (Fig. 6.84). [22] The Legion hall is a sanctuary for the ex-servicemen who find that civilian life is filled with conflict as much as any theatre of war, a refuge that recalls the soldiers’ home in the earlier film, Lightnin’ (1925), and Ford’s own Field Photo Farm.

Social and Cultural Influences

Whilst there is little to celebrate in terms of the evolution of ethnic representation in Ford’s Universal work, the films he made at Fox provide evidence of a more thoughtful approach to the cinematic depiction of ethnicity, particularly as regards the portrayal of Native Americans. Other ethnic groups, however, such as African Americans and Asians do not fare so well on the screen in the period 1921 to 1926, although white ethnic minorities, such as the Irish and the Italians, are shown to be emblematic of the ‘melting pot’ that defined American society in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Irish characters also now start to appear in a large number of Ford’s films in this period, indicating the beginning of the director’s consuming interest in all matters relating to his parents’ homeland.

Ford continues to investigate the theme of civilisation versus wilderness, as exemplified in the Fox Westerns, but also in other genres as well, such as the Irish horse film The Shamrock Handicap (1926), and in the Americana form embodied by Just Pals (1920) and The Village Blacksmith (1922). As will be shown, this key Fordian theme evolves from one associated purely with the settling of the West to a motif that transcends genre. Ford’s appropriation of the imagery of painters such as Remington and Russell in the depiction of landscape also continues throughout this phase of his career, specifically in the two major Fox Westerns, The Iron Horse (1924) and 3 Bad Men (1926).

Ethnicity

Bogle states that, by the 1920s,

Hollywood […] gradually [cast] Negro actors in small roles. Noble Johnson, Rex Ingram, and Carolyn Snowden were among the early bit players in such silent films as The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1923), The Thief of Bagdad (Raoul Walsh, 1924), Little Robinson Crusoe (Edward F. Cline, 1924), The Navigator (Buster Keaton, 1924), The Big Parade (King Vidor, 1925),The First Year (Frank Borzage, 1926), Topsy and Eva (Del Lord, 1927),King of Kings (Cecil B. DeMille, 1927) and In Old Kentucky (John M. Stahl, 1927).(Bogle, 2001, p.33)

This was not necessarily a radical step forward as far as the Hollywood treatment of onscreen African Americans was concerned though; Cripps points out that, ‘In the 1920s servile roles reached 80 percent of all black roles’ (Cripps, 1993, p.112). Bogle contends that, due to the reaction of the negative portrayal of black Americans in The Birth of a Nation (1915), ‘during the 1920s, audiences saw their toms and coons dressed in the guise of plantation jesters’ (Bogle, 2001, p.18).

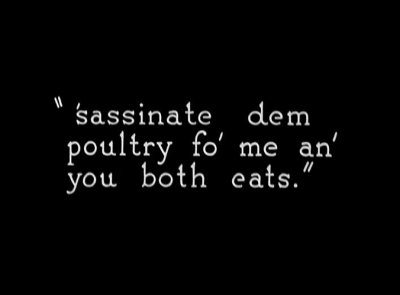

Bogle’s assertion is confirmed by Ford’s first Fox film, Just Pals (1920). In an attempt to find work, Bim turns up at a chicken farm where the black chef requires Bim to kill chickens for him. Although the title card accompanying the scene conveys the inarticulacy of the chef, his obliging nature dilutes the fact that a white man is shown

being forced to seek work from an African American (Figs. 6.85 & 6.86). This sequence also appears to be one of the rare examples in a Ford silent film in which dialogue is attributed to a black character. The African American figures in Cameo Kirby (1923), for instance, feature as mere nonentities who sing and dance at the drop

of a hat (Figs. 6.87 & 6.88), adhering to the portrayal of slaves as benign ‘pickaninies’, non-threatening and almost child-like in demeanour.

Thomas Cripps singles out Ford’s film Kentucky Pride (1925) as an example of the director’s movement away from the traditional representation of black Americans on screen. He argues that ‘the [African American] horse trainer

[…] was an instance of an earthy new type, often uncredited, which departed slightly from Southern tradition’ (Cripps, 1993, p.121) (Fig. 6.89). This apparent progressive step forward in the depiction of African Americans is, however, marred by the stereotypical style of speech attributed to this character (Fig. 6.90). What Cripps does not point out is the presence of another black American figure in the same film, a butler, who, unlike the actor playing

the stable boy, is actually listed in the credits under the name George Reed (Fig. 6.91). The reference to Reed is just as significant, if not more so, than the way in which the other black American character is portrayed in the film. As a named actor, Reed is recognised and assigned a profile not afforded to the unknown actor mentioned by Cripps.

Somewhat more problematic is the ambiguous depiction of the black American character, Virus Cakes, in The Shamrock Handicap (1926). Ford vacillates between showing Cakes as a stereotypical thug, whilst at the same

time promoting him as a well-dressed comic foil. Cakes is shown as quick to violence (Fig. 6.92), pulling a razor blade from his pocket at the slightest provocation, although the vicious aspect of this character is diluted

somewhat by the nature of his appearance, dressed in similar fashion (Fig. 6.93) to the suited African American in Bucking Broadway (1917). The major difference between the portrayals of these characters in both films is two-fold. First of all, Cakes actually has a name, bestowing upon him an element of importance that is not accorded to the African American figure in Bucking Broadway (1917). Secondly, Ford privileges Cakes with a number of close-ups throughout The Shamrock Handicap (1926), thus building curiosity and expectation on behalf of the

spectator as to the importance of Cakes as a subsidiary character (Fig. 6.94) . That this expectation comes to nothing, particularly when he disappears suddenly from the story, does not diminish the evolutionary leap that Ford makes in foregrounding a black character, albeit briefly, in the storyline. [23]

The film also pulls no punches when it comes to other ethnic groups, one title card proclaiming the Jews and the

Irish to be a winning combination when it comes to horse racing (Fig. 6.95). There is a sense in this allusion to other ethnicities that Ford is pandering to the dominant stereotypes of the time, rather than expressing a personal view or prejudice towards such groups. In fact, as discussed in the following chapter, there appears to be no biographical evidence available to suggest that Ford’s personal attitude towards ethnic groups was in any way prejudicial or derogatory.

According to Cripps,

If a moviegoer watched the growth of a black cinema imagery through the twenties, Negroes would seem to have gained far more in artistic stature than any other group. By the 1920s immigrants, Orientals, and Indians developed into stock figures, irrelevant to industrial America except as romantic icons. Each had been a part of the American experience, but in turn each had atrophied into wooden figures of assimilationist sentimentality, tragically vanished aborigines, and inscrutable menace. (Cripps, 1993, p145)

Confirmation of the onscreen depiction of Native Americans as described by Cripps can be found in North of Hudson Bay (1923). The old Native American woman sharing the screen with Tom Mix is crudely drawn as almost

childish, and enamoured of mirrors shiny objects (Fig. 6.96). Her assumed low intelligence is further highlighted when Mix steals her hat whilst she laughs at her own reflection in the newly acquired looking glass. Even though the woman is the subject of mockery, this sequence is also confirmation of Ford’s penchant for using real Native American actors whenever possible.

Apart from the scene between Mix and the old woman, the Native Americans in North of Hudson Bay (1923) literally have nothing more to do other than parade past the camera, and again, apropos the earlier Bucking Broadway (1917), do not feature as main characters in the story. A native woman is shown briefly with four children,

all very young, three of them not yet old enough to walk (Fig. 6.97). The subtext is clear: Native American women are constantly in the process of producing, or about to produce, off-spring, while frequent absence of the male suggests a questionable parentage for the children concerned.

Bearing in mind the stereotypical portrayal of Native Americans in North of Hudson Bay (1923), it comes as a

surprise to see them depicted as both indigent (Fig. 6.98)and noble (Fig. 6.99) in The Iron Horse (1924). This contradictory portrayal of members of the same ethnicity underlines ambivalence on behalf of Ford towards the indigenous natives of America, although, as Edward Buscombe maintains of both The Covered Wagon (1923) and The Iron Horse (1924), ‘Indians feature merely as one of the hazards of westward expansion overcome by the whites’ (Buscombe, 2010, p.92). The director eventually starts to depict Native Americans in a more sympathetic manner a few years later in 3 Bad Men (1926), so The Iron Horse (1924) may therefore be considered to represent a small, yet significant, turning point for the director in his attitude towards the portrayal of this once proud race.

Although, on the surface, The Iron Horse (1924) may be construed as a hymn to multi-culturalism, the mise-en-scène does on occasion elevate the position of the white American community over the other ethnic groups. In the

image shown of the completion of the railroad (Fig. 6.100), we can see that the task is celebrated by the white overseers, whilst the ethnic workers who have actually toiled to lay the rails are consigned to the background. The image also demonstrates Ford’s attitude towards those who lost their way of life in the name of civilisation. Although the Native American to the left of the frame is excluded from the celebrations, he retains his dignity by remaining on his horse, physically and morally elevated above those who have taken the land away through force.

Ford did not fully engage with the plight of the Native Americans until almost the end of his career, with Cheyenne Autumn (1964), in which they were the main protagonists of the story. The journey towards his enlightened portrayal of this much maligned race starts with 3 Bad Men (1926). This film is the first of the director’s extant silent titles to depict Native American figures as something other than nonentities or cursory characters. All of the images relating to this ethnic group present the natives in an informed manner, with the opening sequence

portraying their lives as idyllic and almost Utopian in nature (Fig. 6.101). The figure in the foreground looks upon a mise-en-scène that features a running river and towering snow-peaked mountains that accentuate the concept of the wilderness as the Garden of Eden.

Ford leaves behind the practice of making fun of Native Americans by endeavouring to show the innate nobility

(Fig. 6.102) of those who are about to lose their land, the wagons of the settlers sailing across the plains in the background oblivious to the plight of the people they are about to displace. The natives in the foreground stand still, whilst progress, in the form of the wagon train and the herd of cattle in the background, forges ahead, indicating the eventual suppression of not just a race, but the disappearance of a complete culture and a way of life.

When Ford once more returned to the genre with Stagecoach (1939), the Native Americans are relegated to mere

ciphers within the narrative (Fig. 6.103). Almost ten years later, the themes interrogated in Fort Apache (1948) embrace a post-war disenchantment with the military, at the same time elevating the depiction of Native Americans to a more prominent on-screen role. In Ford’s revisionist stance on a thinly-veiled retelling of the story of General Custer and the defeat at the Little Big Horn, he subverts the accepted viewpoint of the military authorities as honourable and glorious. The flawed hero of the film, Lt. Col. Owen Thursday, as played by Henry Fonda, is portrayed as an arrogant, stiff-necked martinet, with scant regard for honour when it comes to dealing with the Apaches in his pursuit of glory. Conversely, the Native Americans are now literally given a voice for the first time in a

Ford Western, through the character of Cochise (Fig. 6.104). The presence of Cochise, in what is ostensibly a work of fiction, provides another example of Ford’s inclination to feature real-life characters in his films to infuse the narrative with an element of historical validity. A year later, Ford revisited military frontier life for the second part of his unofficial cavalry trilogy. She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949) is more a rumination on age than it is on the role of the military and the Native American in the battle for the West. The Native Americans, however, are portrayed with

dignity and nobility, the narrative affording the character Pony That Walks (Fig. 6.105) a dialogue sequence with the main star of the film, John Wayne. It should also be noted that Ford employs a real Native American, Chief Big Tree, to play the leader of the Apache tribe, rather than resorting to the usual Hollywood practice of the time of using white American actors in disguise. [24]

The last part of the cavalry trilogy, Rio Grande (1950), is somewhat problematical. The role of the Native American is once again relegated to that of the faceless brutal savage, not far removed, if at all, from their portrayal in Stagecoach (1939). Joseph McBride argues that the film can be read ‘as Ford’s early-warning allegory of the Korean War, which broke out ten days after it began filming’ (McBride, 2003, p.504), going on to suggest that the director’s ‘reversal on the subject [of the portrayal of Native Americans] probably meant that he regarded the “Red Indians” in Rio Grande more as “Reds” than as Indians’ (McBride, 2003, p.505). [25]

By the time Ford made The Searchers (1956), his disillusionment with the military is complete. Instead of the heroic Seventh Cavalry riding to the rescue at the last moment, as seen in Stagecoach (1939), this time it is a group of Texas Rangers who are tasked with rescuing the kidnapped niece of Ethan Edwards from a tribe of Comanche warriors. The only military figure of any consequence is a young officer, Lt. Greenhill, portrayed as an object of derision throughout the film.

Ford’s emerging revisionism towards the plight of the Native American is highlighted in a sequence in which Ethan and his brother’s adopted son, Martin Pawley, come across a burnt-out Comanche village that has recently been

attacked by the Seventh Cavalry (Fig. 6.106). Instead of depicting death as an act of moral retribution by the settlers, Ford lingers on the fate of Native Americans who have fallen victim to the policy of enforced resettlement. The body of Look, a Comanche woman whom Martin Pawley had mistakenly taken for a wife, is also found in the same village. Even though Look is initially depicted as a figure of ridicule and fun, similar to the native woman in North of Hudson Bay (1923), Ford personalises her death by having introduced the character earlier on, ensuring that audience empathy for Look and the other slain Native Americans is totally engaged.

Some of the shots in this sequence would not be deemed out of place in later liberal Westerns such as Soldier Blue(Ralph Nelson, 1970) or Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1970). In fact, the latter film deals more conspicuously with the same incident that Ford refers to obliquely in The Searchers (1956), in which Custer and his troops purportedly killed and wounded thirteen unarmed Native Americans at the battle of the Washita River in 1868. Ford was openly critical of the infamous cavalry general, stating that ‘the cavalry weren’t all-American boys, you know. They made a lot of mistakes. You just mentioned Custer, that was a pretty silly goddam expedition’ (in McBride and Wilmington, 1975, p.45).[26]

In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich on the set of his last Western, Cheyenne Autumn (1964), Ford stated that he had wanted to make this particular film for quite a long time, admitting that he had ‘killed more Indians than Custer, Beecher and Chivington put together. There are two sides to every story, but I wanted to show their point of view for a change. Let’s face it, we’ve treated them badly – it’s a blot on our shield; we’ve cheated and robbed, killed, murdered, massacred and everything else, but they kill one white man and, God, out come the troops’ (in Bogdanovich, 1978, p.104).