Introduction

This chapter will consider the titles Ford directed for Fox between 1927 and 1930, a period that began with the totally silent Upstream (1927), followed by a combination of films with synchronised and full sound, through to the release of the late part-silent title Men Without Women (1930). The evolution and development of major Fordian themes such as family, ritual and ethnicity, with particular emphasis on the heightened attention to the theme of mother-love, will continue to be considered, along with how the innovation of sound underlines the importance that music plays in the films of John Ford. The key themes of civilisation versus wilderness, and landscape as character are not particularly prevalent in Ford’s work during this period, and are therefore not included in this chapter.

All of the other key themes will be interrogated, as with the previous chapters, in relation to questions of authorship, and in the context of Ford’s progression from individual journeyman to a brand, or author function. Taking into account Edward Buscombe’s assertion that ‘a film is not a living creature, but a product brought into existence by the operation of a complex of forces upon a body of matter’ (Buscombe, 1993, p.32), the chapter will also continue to investigate the relationship between technological innovation and the development of Ford’s distinctive style. This approach is extremely pertinent in the interval that covers the introduction of sound.

Ford’s profile continued to grow to the point where his peers elected him president of the ‘Motion Picture Directors Association in 1927’ (Levy, 1998, p.15). As will be discussed, those who wrote about the film industry also began to recognise him as a major directorial talent. Ford carried on working as an unaccredited assistant director during this period and, in the case of Borzage’s Seventh Heaven (1927), successfully interpolated a number of his own visual motifs into the film, indicating that he was continuing to evolve as an auteur whilst working within the constraints of the Hollywood studio system.

One of the major influences on the director’s work from this period is that of the German director F.W. Murnau. The effect that Murnau’s style had on Ford’s Four Sons (1928) is obvious, with Ford continuing to revisit a number of the German director’s visual motifs into the thirties and forties. Also, by now, the Ford stock company becomes a permanent fixture in terms of both cast and crew, with the director going on to employ this working methodology throughout the rest of his career.

Fox Corporation

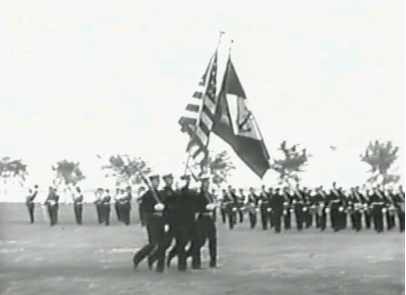

The films John Ford directed in his late silent period for the Fox Corporation steadfastly excluded the Western, a genre that would remain in decline until the late 1930s.[1] Instead, he continued to work in forms still fairly unfamiliar to him, including the war film Four Sons (1928); and three Irish films: Mother Machree (1928), Hangman’s House (1928), and Riley the Cop (1928). There is a good chance that, if Ford had not been so closely associated with the Western form, he would be just as well known for the war films he made. Ford eventually directed ten full length features about modern warfare: two in the silent era, The Blue Eagle (1926) and Four Sons (1928); and eight titles after the coming of sound, as well as a further eight documentaries dealing with war. The opportunity for Ford to direct Four Sons (1928) at Fox should therefore not be taken lightly when considering the evolution of Ford’s style. Aspects of the genre, such as military ritual, loyalty, honour, and self-sacrifice, underpin the ‘Fordian sensibility’ as much as the primary motifs of family, civilisation versus wilderness, and religion that have come to be associated with his Westerns.

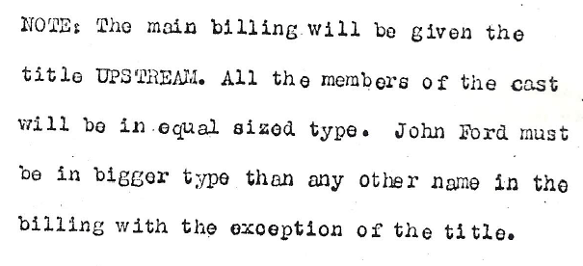

Ford’s reputation and standing, both inside and outside of the industry, developed further still. Tag Gallagher writes that, ‘Ford, with the success of such high-budgeted specials as Four Sons (1928) (possibly Fox’s top grosser), and Mother Machree (1928), found himself at the top of the heap of Fox directors, flanked, in company promotion, by the likes of Walsh, Hawks, Borzage, Murnau, and [John] Blystone’ (Gallagher, 1988, p.49). To prove the point, in 1927 the studio specified in a memo to exhibitors that publicity billing for Upstream must feature Ford’s name

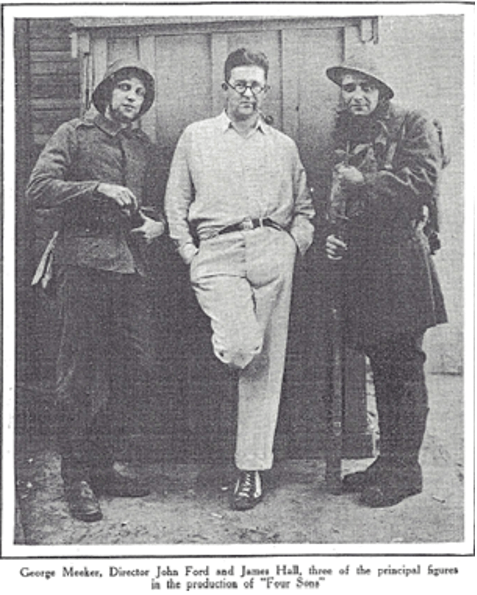

bigger than any other name apart from the film title itself (Fig. 7.1). Towards the end of the 1920s Ford’s stature was such that he was profiled in studio press releases relating to the production of Four Sons (1928), the caption under

the photograph (Fig. 7.2)[2] at the beginning of the article proclaiming that ‘Jack Ford is a regular fellow’.[3] studio publicity shot from the same film suggests that Ford is regarded as one of the principal figures in the production of

the film (Fig. 7.3).

A look at some of the other promotional materials from around this period also indicates Ford’s growing importance to the studio, furthering both his exposure to the public at large as a ‘name’ director, and contributing to the creation of the brand ‘John Ford’. The poster for The Blue Eagle (1926) features Ford’s name prominently at the bottom, with the director also credited as producer, although the name of the studio owner, William Fox, is equally as prominent

(Fig. 7.4).

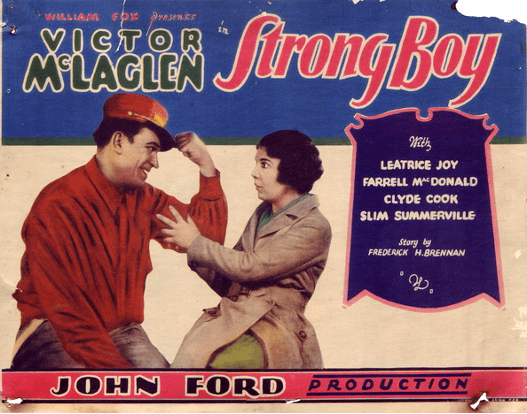

Two years later, not only is Ford’s name more eminent than his employer, but a poster for Mother Machree (1928) actually features a photograph of him as well. The size of the image highlights the importance of the director over

the actors featured in the film, with Ford’s profile slightly larger than that of anyone else (Fig. 7.5). The director’s name would continue to appear in ever larger print as his career progressed, as a poster from his last totally silent

film, Strong Boy (1929) (Fig. 7.6), shows.

External trade publications also helped to elevate his esteem. Levy states that, ‘The Moving Picture World in November 1927 [called] John Ford “one of the outstanding figures in the directional field”’ (Levy, 1998, p.15). Scott Eyman writes, ‘Ford was now a prestige director whose name was beginning to be known beyond the narrow circle of the film industry and hard-core fans’ (Eyman, 1999, p.112), citing a feature article in the New York Times in June 1928, which ‘appeared under [Ford’s] byline [but] was almost certainly ghosted by the studio publicity department’ (Eyman, 1999, p.112). By the end of the 1920s, the various discourses surrounding the director indicate that ‘John Ford’ was becoming an industry label, rather than merely an individual.

Employed as an assistant director, Ford was well placed to apply his thematic imprint onto the work of others. Apart from Nero (1922), Ford also made anonymous contributions to at least two other prestige Fox titles during the 1920s, What Price Glory? (Raoul Walsh, 1926),[4] and Seventh Heaven (1927). Lefty Hough recalls working on What Price Glory? (1926) ‘out among the pepper trees. Motorcycle sidecars and trucks going to the front. We went out there with Victor McLaglen’. On Ford’s contribution to Borzage’s Seventh Heaven (1927), Hough states that, ‘The Ford company was given the assignment to bring the taxi cabs into Paris’ (Transcript of interview with Dan Ford, John Ford collection at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington).

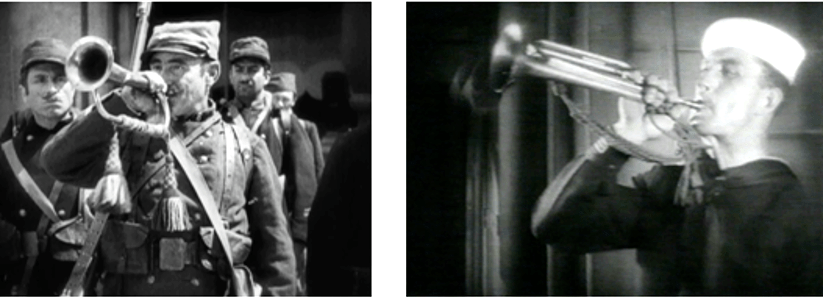

The sequence that Hough refers to in Seventh Heaven (1927) contains a number of visual motifs that would not have looked out of place in one of Ford’s own films. There are numerous examples of crowds waving and cheering

as the military move off to war, this time in taxi-cabs as opposed to riding on horses (Fig. 7.7). A bugler summons the troops before the battle commences (Fig. 7.8), an image Ford also used in The Blue Eagle (1926) (Fig.7.9),

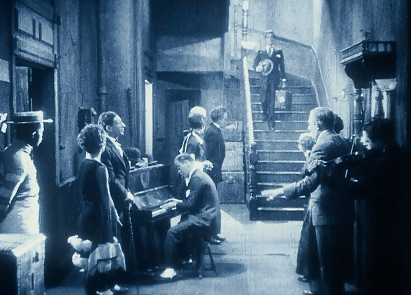

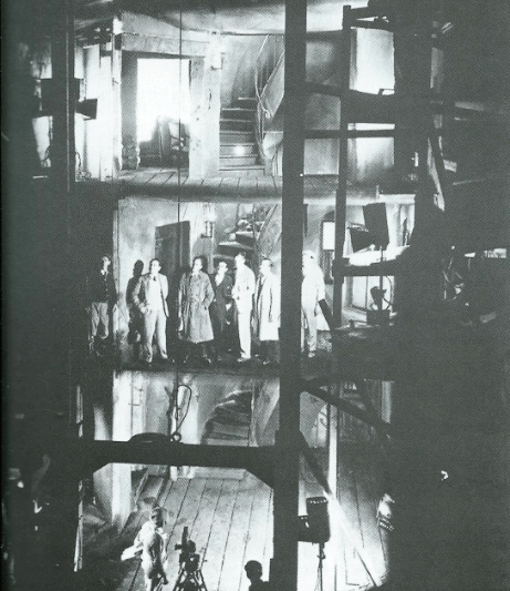

whilst the charging soldiers on horseback (Fig. 7.10) are not dissimilar to comparative scenes in Ford’s Westerns, as featured in 3 Bad Men (1926) (Fig. 7.11). These images further indicate the emergence of a distinctively ‘Fordian’ style. The link to Ford’s own work is complete when he shoots on the same set that he would himself use for Four

Sons (1928) (Fig. 7.12), which had been built previously for Murnau’s Sunrise (1927).

With regards to Ford’s stock company, Victor McLaglen vied with J. Farrell McDonald as the most prominent onscreen member of the director’s acting group during the years 1927 to 1930. McDonald ended up appearing in approximately 15 of the 37 titles Ford made during the 1920s, but it was McLaglen’s star that began to rise towards the end of the decade, as McDonald’s general role of the Irish everyman eventually fell upon his shoulders.

The previous chapter argues that Ford’s early Fox films do not significantly reflect the impact of a stock company, whereby the portrayal of a character by the same actor or actress provided continuity of character from title to title. The exception to this, however, is J. Farrell McDonald. In Kentucky Pride (1925), he plays Mike Donovan, who at

various times throughout the film works as a horse trainer and a policeman (Figs. 7.13 & 7.14). A close look at both

3 Bad Men (1926) (Fig. 7.15) and Riley the Cop (1928) (Fig. 7.16) shows that the characters are almost interchangeable; McDonald’s turn in Kentucky Pride (1925) literally a dress rehearsal for the later films. The players might change, but the character type embodied by actors such as McDonald and McLaglen remains constant.

In the absence of George O’Brien and the demotion of J. Farrell McDonald from leading man after Riley the Cop (1928), the role of the outsider as a man of action fell to McLaglen, with more emphasis on the solipsistic nature of the outsider. As with 3 Bad Men (1926), Ford also now appears to be moving even further away from the traditional prominence of the romantic leads, and manoeuvring the outsider to the forefront of the story. In Hangman’s House (1928), the young couple, Connaught and Dermott, are usurped within the narrative by Citizen Hogan, played by McLaglen, who takes centre stage. A clue to this evolutionary shift in the focus of the narrative may be found in a comment from the actress Madge Bellamy, who played the female love interest in The Iron Horse (1924). According to Bellamy, ‘If it was a simple love scene, he didn’t appear to be terribly interested. So he didn’t pay too much attention in what you were doing unless it was something dangerous and exciting’ (in Drew, 1989, pp.22-23).

It is difficult to conclude whether the move towards the male protagonist as outsider, free from any romantic entanglement, was attributable to Ford or the scenario writers with whom he worked at the time. What is irrefutable, however, is that the ‘good bad men’ protagonists of 3 Bad Men (1926) and Hangman’s House (1928) both represent a departure for Ford from the narratives that had gone before. Characters such as Citizen Hogan provide a direct link to later Fordian figures who are ostracised from the communal group. Moreover, the final act of Hangman’s House (1928) also points towards what would eventually become a major feature of Ford’s later work, the absence of a happy ending. Hogan is left without a home in his native land by the end of the film, and forced into exile abroad.

The presence of other directors at the same studio also had a noticeable effect on the director’s work. Having eschewed the practice up to the mid-1920s of using outside foreign directors – as opposed to other studios such as Warner Brothers with Michael Curtiz and MGM with Erich Von Stroheim – Fox lured the celebrated filmmaker F.W. Murnau from Germany in 1926 to make his first Hollywood film, Sunrise (1927). According to the silent film historian Richard Koszarski, the head of the studio, William Fox, ‘encouraged the studio’s other contract directors – solid American types like John Ford, Raoul Walsh and Frank Borzage – to study Murnau’s style and take from it what they could’ (Koszarski, 1990, p.86).

The influence of Murnau upon Ford’s visual style was practically immediate. The most obvious change in style is the experimentation in moving the camera, a rare event in a Ford film up until a year or so before he directed Four Sons (1928). Upstream (1927) features a number of tracking and dolly reverse shots, as well as a forty-five second long take, which will be discussed in more detail further on in this chapter. In Upstream (1927), however, these sequences do not possess the same assurance and fluidity of camera movement as displayed in the later film.

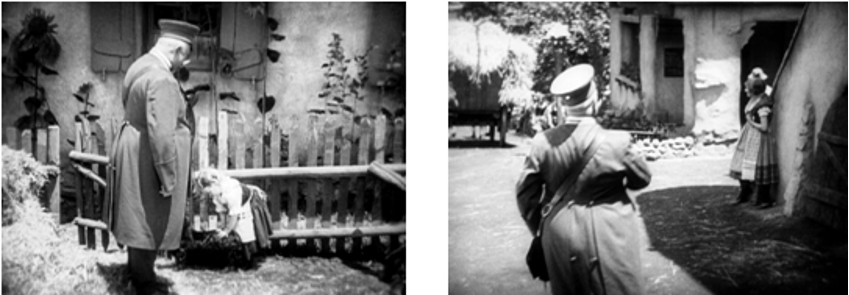

The opening shot of Four Sons (1928) features a fifty second uninterrupted take, in which the village postman is first seen talking to a small girl (Fig. 7.17). The camera follows in his footsteps as he strolls through the village, ending up on another two-shot of the postman and an older girl (Fig. 7.18). Murnau also includes a long take at the beginning of Sunrise (1927), approximately the same length, following the short journey of a femme fatale as she makes her way through the village at night.

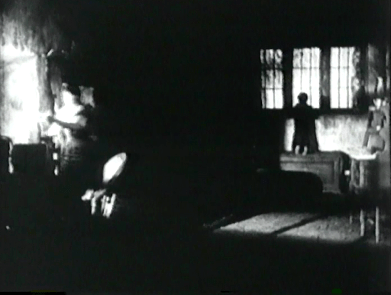

The mise-en-scène of Four Sons (1928) gives the impression that the film could have been directed by Murnau

himself; the use of deep focus, and the contrast between shadow and light (Figs. 7.19 & 7.20), suggest an unusually close affinity with Murnau’s expressionistic style. Ford also appropriates Murnau’s predilection for shadows and

light, with the silhouette of a figure on the wall heralding the arrival of unwanted news (Fig. 7.21), a shot comparable to a similar image from Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) (Fig. 7.22).

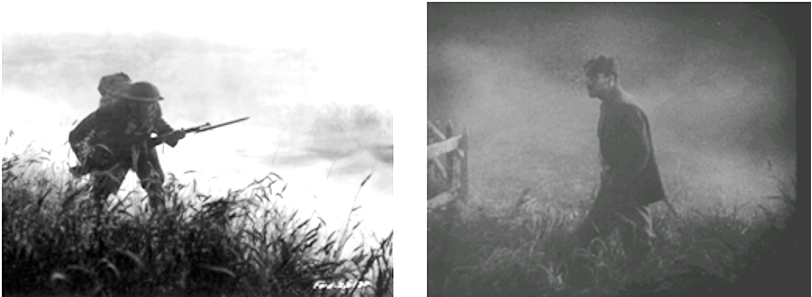

In Four Sons (1928), the postman delivers a letter telling the mother she has lost yet another son in the carnage of war, whilst the shadow of the vampire in Nosferatu (1922) is a precursor to imminent death. Ford also evokes the atmospheric style of Murnau by filming his characters walking through a mist- covered landscape, similar once

more to another sequence in Sunrise (1927) (Figs 7.23 & 7.24).

Gallagher suggests that Four Sons (1928) is ‘an almost self-effacing imitation of Murnau’s style’ (Gallagher, 1988, p.50). He goes on to suggest that up until this point Ford’s movies had been ‘relatively unstylized’ (Gallagher, 1988, p.50), but Murnau’s approach to mise-en-scène directly influenced Ford’s use of lighting ‘to create dramatic mood through emphatically contrasting blacks and whites, macabre shadows […] and other abstractions’ (Gallagher, 1988, p.50).[5] As Eyman and Duncan maintain, ‘Ford’s response [to Murnau] was to meld his own interests – family, community – with Murnau’s style – stylized studio art direction and flowing tracking shots [and subsequently] the student quickly became a master’ (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.67).

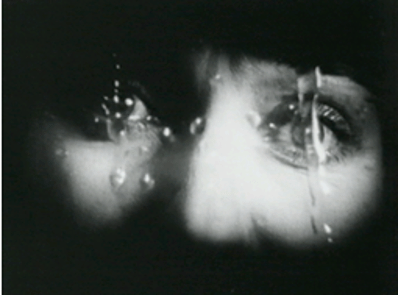

What Eyman and Duncan do not point out is that Murnau’s influence on Ford was not restricted to just the one film. For example, in his dying moments, ‘Hanging Judge’ James O’Brien in Hangman’s House (1928) is visited by the

numerous ghosts of those he has wrongfully sent to the gallows (Fig. 7.25). Murnau employs a similar montage of images in Sunrise (1927) (Fig. 7.26), as the main character, a young farmer – played by George O’Brien – is tempted by the allure of the big city.

Ford would occasionally incorporate an element of expressionistic style in his later work, most notably in The Informer (1935), The Long Voyage Home (1940), and The Fugitive (1947), but in the main, Murnau’s aesthetic of mist, montage and shadows remains firmly rooted within Ford’s late silent period.

Autobiographical Influences

Although the theme of family is still present in the films Ford directed from 1927 to 1930, it is the sub-theme of mother-love that increases in intensity, specifically in Mother Machree (1928) and Four Sons (1928). The onscreen family, as depicted by Ford, still continues to disintegrate and fracture but, in this form, the mother remains the centre of the communal group. Also, it is through the continuing evolution of the themes of family, ritual, Irishness and religion that the director’s style starts to take more distinctive shape in the years 1927 to 1930, indicating an increased conscious effort to explore personal motifs and themes, irrespective of genre.

The Family Unit

During the last decade of the silent era, Ford was in the process of establishing a married life of his own. This perhaps explains the foregrounding of the family unit within the films he made during the 1920s. His later films emphasised the fracturing of the communal group even more prominently than before, which suggests Ford’s increasingly cynical attitude towards family life. As Lindsey Anderson proposes, ‘[his vision of family] is authentic, buried deep no doubt in the artist’s childhood, in some experience of community early on, lost and longed for, which he could never recreate in his own family life’ (Anderson, 1981, p.205).

Although Upstream (1927) does not specifically address the dynamics of the family unit, the group of actors and vaudeville acts thrown together in a boarding house mirror an extended family. In fact, this small community is the

genesis for the creation of family, with two of the members eventually marrying (Fig. 7.27). In a scene that bears comparison with The Searchers (1956), the wedding ceremony is interrupted by the sudden arrival of an outsider (Fig. 7.28), an actor who has previously left the group behind to enjoy success on the London stage.

In Hangman’s House (1928), Citizen Hogan is instrumental in ensuring that the lovers Connaught and Dermott are finally free to marry and start a family, by ridding the community of the villain John Darcy. Just like 3 Bad Men (1926), the film suggests that figures like Hogan, on the fringes of society, are just as important to the creation of this close social group as those who seek to establish their own family unit.

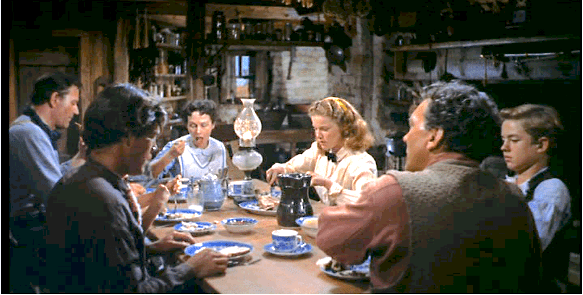

The mother-love titles directed by Ford during the silent era all feature the matriarchs both as widows and as the driving force within the family unit. In the films that fall outside of that genre, yet still deal with the theme of family, the mother is still consistently portrayed as the centre of the group. The mother figure of Ford’s silent films, along with later incarnations such as Ma Joad in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and Mrs Jorgensen in The Searchers (1956), are shown as forceful and determined, yet always deferential to the needs of the family. For example, Frau Bernle, the mother in Four Sons (1928), is portrayed as a subservient figure, although the mise-en-scène suggests

the respect in which she is held, with a seat reserved for her at the head of the table in the place of an absent patriarch (Fig. 7.29).

A consistent pattern in all of Ford’s mother-love films is the total absence of a dominating father figure. This removes the potential for conflict between husband and wife, freeing the matriarch to undergo the associated sufferings of a single mother, and, in most cases, to bear that suffering with fortitude. Ellen McHugh in Mother Machree (1928) is the archetypal Fordian mother, both in terms of the emotional turmoil she must go through before she can be reunited with her lost family, and in her physical bearing as an older woman in her fifties.

When Ford does acknowledge the absence of the father figure, as in the passing of the husband at the beginning of Mother Machree (1928), it also signifies the death of the family unit, with Ellen McHugh forced to give up her son for adoption so he can live a better life. The lack of a father figure in Silver Wings (1922) also results in a mother losing her children. In both films the matriarch fails to hold the family together, and suffers accordingly, although the family is eventually reunited.

Mother Machree (1928) is one of the most overt examples of the mother-love films that Ford made for Fox. The fact that the story tells of an Irish mother, Ellen McHugh, who leaves Ireland for America, adds an autobiographical element to the film; McHugh’s humble beginnings in a small village arguably mirror the life of Ford’s own mother. The role of the matriarch within the family hierarchy, as depicted in Ford’s work, is therefore surely a reflection of the director’s own family. A photograph taken in 1929 of Ford with his mother, Abby, shows him kneeling deferentially

as she straightens the Mother’s Day rose in his lapel (Fig. 7.30). The image could almost be mistaken for a still (Fig. 7.31) from one of the director’s films, such as Four Sons (1928). A comparison between the physical appearance of Ford’s mother and the cinematic matriarchs discussed so far offers an image of strong-willed individuals, rarely frail in demeanour or countenance, grey of hair, and always dressed demurely. The temperament of these mother-figures recalls Ford’s own mother, a woman described by Ford biographer Ronald Davis as occupying ‘the central role [in the family], always a devoted homemaker and a strict disciplinarian with her children […] [and] the dominant force in the Feeney household’ (Davis, 1995, p.21). The majority of Ford’s mother-figures also seem to be of a mature age, as was his own mother Abby, who was already in her early 60s by the time her son started directing in 1917.

The only time that Ford, whilst working in the mother-love genre, portrays a mother as a young woman (Fig. 7.32) is

in Mother Machree (1928), though by the time the story has run its course, the image of the matriarch reverts to type (Fig. 7.33). The sequences featuring the older Ellen in Mother Machree (1928) are quite brightly lit, accentuating the angelic qualities of her persona. In contrast, Ford places the younger version of the mother within

a much darker and doom-laden mise-en-scène (Figs. 7.34 & 7.35). She is also favoured with a close-up shot – a rare occurrence in any Ford film – her grief pre-echoing the further suffering to come (Fig. 7.36). Although it cannot be claimed that the director’s portrayal of the mother-figure is free from the conventions of popular stereotype, certain aspects of his own personal relationship with Abby Feeney do seem to inform the character of the Fordian mother.

The fact that Ford is able to incorporate aspects of his own biographical background when depicting the mother figure may possibly explain his continued attraction to the genre. The mother-love genre was still popular with both studios and audiences alike when Mother Machree (1928) was followed by the release of Four Sons (1928) in the

same year. In this film, a mother (Fig. 7.37) loses three of her four sons in battle during World War I. Prior to the war, her other son leaves Germany to live in America and, after the conflict is over, the mother and her surviving son are finally reunited.

The portrait of Frau Bernle has much in common with Mother Machree (1928), with the mother yet again depicted as a sainted matriarch, as well as a widow. There is a tangible undercurrent of sexuality that is missing from Ford’s other mother-love films prior to this, as if the grown children who surround her are surrogate husbands, suggesting a more knowing view towards the potentially incestuous nature of the relationship. This is implied in a shot in which

the mother coyly indicates for one of her sons to move closer to her (Fig. 7.38). The mother looks straight into the camera, her expression obviously denoting tenderness and love towards her son, and the following shot (Fig. 7.39) shows the two of them standing very close together. This son is the one who will survive the war, fighting on the side of America against his siblings. The closeness between the two of them suggests that he is the favoured son, and their eventual reunion in America at the end of the film could almost be described as a celebration of long-lost

lovers, meeting again after years apart (Fig. 7.40).

Along with the close-up, Ford also tends to eschew the use of special effects or trick photography throughout both his early silent and later sound work, preferring a naturalistic mise-en-scène rather than recourse to artifice. One notable exception to this is a sequence in Four Sons (1928), whereby the mother conjures up the spirits of her

children (Fig. 7.41), as a fantasy re-enactment of the time when the family were whole. Yet, even in her imagination, it is noticeable that the patriarch is missing, almost as if the roles of both husband and wife have been taken on by the mother.

Although the mother figure continues as a recurring motif in Ford’s films, the theme of overt mother-love eventually disappears in his later work. In the early sound film, Pilgrimage (1933), Ford presents one of his strongest, and most complex, mother figures: a woman so determined to keep her son tied to the home and thus separated from the woman he loves, that she signs him up to the draft to fight in World War I. The son perishes, and the mother is left to

grieve and eventually realise the consequences of her actions (Fig. 7.42). Ford takes his time before revealing the depth of her anguish, underlining his familiarity with mother figures that hide their emotion for fear of being seen as weak. McBride points out that, ‘in a striking coincidence, Ford’s mother died shortly after filming Pilgrimage’ (McBride, 2003, p.195). The death of Abby Feeney and the devastating portrayal of the repercussions of mother-love appear to signal a watershed in Ford’s depiction of the matriarch. From this point on these mother figures would always tend towards the compassionate, and in the process suppress their feelings rather than endanger the close ties of family.

Ford’s depiction of the mother figure stoical in the face of adversity reaches its apogee in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), with Ma Joad unable to intervene as the family fractures under the weight of events outside of her control. It

is obvious from the mise-en-scène that she, and not the father, is the nucleus around which the family unit revolves (Fig. 7.43). Even when the mother is not central within the narrative, Ford still emphasises the imperturbable

resignation of the matriarch. For example, the character of Mrs Jorgensen in The Searchers (1956) (Fig. 7.44) retains her dignity when faced with the loss of her son, accepting his death as the price to be paid in order to tame the wilderness.

These mother figures not only reign absolute, but they are also shown to be stronger and more resolute than the patriarch. This motif of the weak father-figure seems unique to Ford.

Ritual

Ritual as a major Fordian theme continues to embrace the communal sub-themes of drinking, dancing and music, this last motif accentuated in importance to Ford’s work through the introduction of sound. As mentioned previously, the practice of drinking becomes an acceptable component of the director’s style as long as it is combined with an element of humour, confirmed by both Upstream (1927) and Riley the Cop (1928). In the former

title, the dancing act of Callahan and Callahan spike the punch at a wedding reception (Fig. 7.45) in a scene that foreshadows a similar sequence in the later Fort Apache (1948) (Fig. 7.46). In Riley the Cop (1928) (Fig. 7.47), the

character of the title, temporarily freed from the chains of prohibition in America when abroad in Germany, indulges himself so much that he starts to see four of everything (Fig. 7.48).

Alcohol in a Ford film carries a number of different meanings. For example, it can indicate the inherent loneliness of

a character, such as the alcoholic doctor in Stagecoach (1939) (Fig.7.49), and the cavalry sergeant in Cheyenne Autumn (1964) (Fig. 7.50). Drinking is also a signifier of masculinity, accentuating the bonding of Doc Holliday and

Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine (1946) (Fig. 7.51), or, as in Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), underlining the masculine qualities of the frontier woman (Fig. 7.52).

Drinking as pure ritual can be found in many of the films Ford made on the subject of the military. The lower orders are just as much inclined to observe the ritualistic conventions of alcoholic consumption, such as the three sergeants in Fort Apache (1948), as well as the officers in Rio Grande (1950). However, Ford does not ignore the celebratory aspects of drinking. The sergeant in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) toasts his retirement from the military, before the natural consequences of over-indulgence result in a knock-down brawl with his drinking

companions (Fig. 7.53).

In The Quiet Man (1952), characters drink and fight themselves to a standstill. A closer reading of the film reveals figures such as the matchmaker Michaeleen Og Flynn to be rather sad and pathetic individuals, constantly drunk

and apparently all residing rent-free in the local hostelry (Fig. 7.54). As already discussed in Chapter Five, very rarely, if ever, does the director confront the negative aspect of drinking, preferring to embellish the ritual with associated practices such as friendship and communal singing, and ensuring that alcohol is represented positively as an aspect of social bonding.

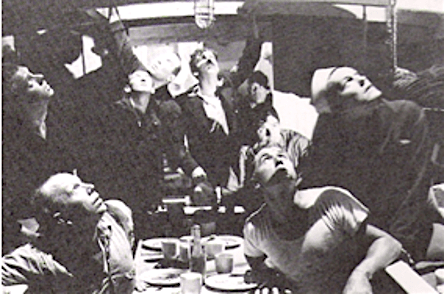

The theme of ritualised eating is as much an instrument to bind community and family as ceremonial drinking. For example, in Upstream (1927), a disparate group of vaudeville players share the table in a boarding house and,

momentarily, bury their differences through the act of dining together (Fig. 7.55). Another aspect to this ritual that is only vaguely hinted at in Straight Shooting (1917), but explored more comprehensively eleven years later in Four Sons (1928), is the empty place at the table to indicate the fractured family group. In Straight Shooting (1917), detailed in Chapter Five, the fracturing of the family caused through the murder of a young relative by land-grabbers is indicated specifically in this way. In Four Sons (1928), the ritual of communal eating also combines with the theme of the incomplete family to underline and heighten the disintegration of the social group. At the

beginning of the film the mother, Frau Bernle, happily dines with her children (Fig. 7.56), performing the ritual of grace for a family unit which is, apart from the missing patriarch, complete and untroubled. Later on, after one son has left and gone to live in America, and two have died in the war, the mother’s prayers are now of grief and sorrow, as she prepares to dine with her remaining son (Fig. 7.57).

Many of Ford’s later films feature a sequence in which a family, or a clique united by a common purpose, sit down as

a group to eat together. The military films, such as Submarine Patrol (1938) (Fig. 7.58) and They Were Expendable (1945) (Fig. 7.59), feature this motif on a thematic level as well, the act of communal dining a required ritual that ensures co-operation and comradeship within the closed military circle.

Visually, the motif of eating reinforces the notion of matriarchy, with the family ‘together at the dinner table, often with the mother at the head of the table’ (Eyman and Duncan, 2004, p.16), but matriarchy is sometimes subverted during the act of eating by the patriarch or male authority figure. In How Green Was My Valley (1941), the father, seated at the dinner table, turns his sons out of the house when they join the labour union, the wife powerless to

stop the disintegration of her family (Fig. 7.60).

Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956) reveals his own bigotry and hatred by referring to the ethnicity of his

brother’s adopted son whilst they are eating together (Fig. 7.61), suggesting eating as ritual can also be an occasion for disruption as well. The hidden tensions in the group of travellers in Stagecoach (1939) is illustrated by the seating pattern of the characters as they prepare to eat, with the prostitute Dallas and the outlaw Ringo left to dine by themselves whilst those who feel themselves to be morally superior move away in judgement to the end of the

table (Fig. 7.62). It can also signify reconciliation of family, as when Sean Thornton in The Quiet Man(1952) drags his brother-in-law and former nemesis, Will Danaher, to the family table once a difference of opinion has been settled in a brutal fist-fight (Fig. 7.63).

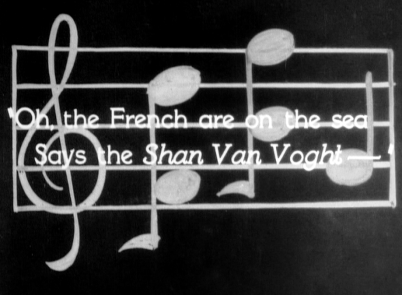

Another major Fordian ritual that defines community – the celebration of music – appears more frequently in Ford’s films from the mid-20s onwards, almost as if he is preparing the groundwork for the introduction of sound. The figure of the actual musician also becomes more prevalent. To the director, music belongs to all members of the social group, and music and song play a part in all the genres in which Ford worked. Kalinak notes that ‘Ford employed many of the same strategies he had used in the silent era to control music in his first sound-on-film feature, Mother Machree (1928)’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.16). This observation is borne out by the way that Ford incorporates a reference to the representation of music with the performance itself. The musical sequence in the

sound synchronised Mother Machree (1928) is prefaced by the lyrics to the title song (Fig. 7.64), similar to the manner in which the lyrics are displayed on title cards for songs performed in The Iron Horse (1924) and 3 Bad Men (1926).

Ford also continues to use music to define character. The melodies that accompany the appearance of the doomed husband, Michael, in Mother Machree (1928), emphasise his Irishness, and in turn pre-echo some of the musical themes of Ford’s later films. In fact, the opening minutes of the film could be described as a dry run for some of Ford’s more accomplished efforts in the Irish genre, particularly The Quiet Man (1952), which features the same traditional Irish tune, ‘The Rakes of Mallow’, as heard in Mother Machree (1928). The earlier film also includes a short sample of the traditional Irish drinking song, ‘Garry Owen’, a piece of music that Ford reprises in two of his cavalry films, Fort Apache(1948) and She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949). As Kathryn Kalinak points out, ‘The song has Ireland written all over it’ (Kalinak, 2007, p.134).

The song from which Mother Machree (1928) takes its name reinforces Ford’s constant love affair with Ireland through music. The lyrics concern the lament of a young man remembering his departed mother, someone who

“loves the dear silver that shines in your hair,

And the brow that’s all furrowed,

And wrinkled with care.

I kiss the dear fingers,

So toil-worn for me,

Oh, God bless you and keep you, Mother Machree”

(Lyric by Rida Johnson Young, Music by Chauncey Olcott and Ernest R. Ball, 1910).

The description of the matriarch in the lyrics could easily apply to Ford’s own mother, along with the sentiment of unequivocal love on behalf of the child for the parent. According to Tag Gallagher, to his mother, Ford ‘was her sweetheart. He looked like her and held her in awe, and in later years […] claimed a psychic bond’ (Gallagher, 1988, p.4).

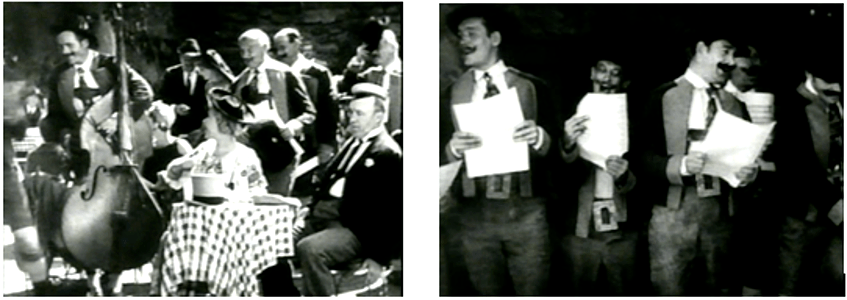

The musicians and musical performances featured in Four Sons (1928) are integral to the fabric of community. A musician serenades a young woman during a hayride as a prelude to romance (Fig. 7.65), whilst the village band promotes harmony within the community at what appears to be a celebration of Frau Bernle’s birthday. The addition

of the accordionist in the film (Fig. 7.66) calls to mind Ford’s practice of using Danny Borzage’s playing of the same instrument off-camera whilst on location; Borzage was a bit-player and musician ‘who provided music on Ford’s sets from The Iron Horse onwards’ (McBride, 2003, p.251).[6]

The totally silent Hangman’s House (1928) also features traditional Irish songs, one piece of music in particular displaying Ford’s Republican sympathies for the suffering of the Irish under British rule. The words to the song ‘The

Shan Van Vocht’ appear early on in the film (Fig. 7.67) as Citizen Hogan traverses the countryside disguised as a monk. Shan Van Vocht translates to the Gaelic for ‘“poor old woman”, a title for the oppressed Irish people. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a Belfast literary journal would arise with the title Shan Van Vocht, devoted to promoting an independent Irish culture’ (Anon, 2011). The song itself is a reference to an aborted attempt by the French in 1796 to free Ireland from the occupational forces of Great Britain. It is doubtful that a contemporary audience would have been aware of the political aspect of the song, but it is likely Ford would have known, suggesting that the director was fully aware, even at this early stage in his career, that music can comment powerfully on both narrative and characterisation.

Music also features quite liberally on both the diegetic and non-diegetic soundtrack of Riley the Cop (1928). As with Four Sons (1928), the film is mainly set in Germany, and to Ford, as well as to contemporary audiences, the inclusion of a band playing in a beer garden reinforces a stereotypical notion of the country. Somewhat less sombre than Four Sons (1928), Riley the Cop (1928) is a counterpoint to the earlier film; one is obviously a war film, whilst the other is a comedy. The musicians whom Riley encounters on his travels are presented as professional paid

entertainers (Figs. 7.68 & 7.69), as opposed to the itinerant musicians depicted in Four Sons (1928).

Another major ritual associated with Ford, closely entwined with music, is dancing. The presence of this communal activity, as explored in Four Sons (1928), underscores the continued existence of society. In a period initially

unencumbered by thoughts of war, the villagers gather to celebrate their idyllic community (Fig. 7.70). The occasion also involves courting for the younger generation, thus ensuring that the community endures.

The rituals of dancing, drinking and eating in Ford’s films also continue to evolve as his work makes the transition from silent to sound. Early sound titles such as Salute (1928) and Men Without Women (1930) both contain

examples of the first of these two motifs (Figs. 7.71 & 7.72). Hangman’s House (1928) features an early illustration of what was to eventually become a key thematic ritual in Ford’s later military films, the ceremonial meal in which

the rules of etiquette are strictly observed (Fig. 7.73). The opening sequences to both this film and the later sound title The Black Watch (1929) (Fig. 7.74) demonstrate the smooth progress that these typically Fordian motifs make from the silent to the sound era.

Irishness

Lourdeaux points out that ‘Ford’s 1920s films often presented Irish-American stereotypes: the boxer, the drinker, the jockey, the devoted son, and of course the policeman’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, p.95). Film scholars and writers are divided between those who suggest that this trait is ‘the source of what [is] arguably some of the most disparaging images of the Irish to have appeared in American cinema’ (Morgan, 1997, [n.p]), whilst others argue that ‘the same kind of humour is accepted in Shakespeare’s comic relief, so why not Ford’s?’ (Barra, 2001, [n.p]).

Opinions such as Morgan’s imply that Ford’s view of the Irish was constant, in that all of his Irish characters fit the stereotype. A close look at those examples of Ford’s work featuring the Irish or Ireland would seem to counter this suggestion. For instance, Ford does not shrink from showing the disdain of the Irish towards their fellow countrymen in later sound films such as The Informer (1935) and The Quiet Man (1952). Gypo Nolan, the informer of the title, is shown to be a drunkard prepared to betray one of his own for money. In The Quiet Man (1952), members of the community are portrayed as either backward in their attitude to women – Sean Thornton being encouraged by a female villager to beat his wife with a stick (Fig. 7.75) – or prepared to fight at the drop of a hat.

Although Eyman and Duncan catalogue the Irish in Ford’s films as a visual motif, the director’s love for his own heritage is more of a thematic than a visual trait; it is ingrained within many of his films, to the point where it cannot be separated from the fabric of Ford’s oeuvre as a whole. The obvious Irish films in Ford’s later work include The Informer (1935), The Plough and the Stars (1936), The Quiet Man (1952), The Rising of the Moon (1957), and Young Cassidy (1965). This would ignore, however, the multitude of Irish characters that appear in numerous other Ford films. For example, the director reflects the multiculturalism of the early West by populating his cowboy films with Irish characters such as Michael O’Rourke, Sergeant Mulcahy, and Sergeant Quincannon in Fort Apache (1948); Quincannon also appears as a main character in She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950).

The expression of Irishness in Ford’s film work intensified further in the late 1920s. This is demonstrated by the fact that the narratives of both Mother Machree (1928) and Hangman’s House (1928) take place partially, in the case of the former, and fully in the latter, in Ireland itself. Mother Machree (1928) covers some of the same ground as The Shamrock Handicap (1926), the story starting in Ireland before following the characters as they move to America.

Again, the film (Fig. 7.76) also offers a somewhat sentimentalised view of Ireland withyoung children, shoeless but happy, reading a book in the middle of a picture-postcard village. At times, the mise-en-scène is almost mythical. Ford conjures images of a fantasy world, represented through the pages of a book of paintings; a land that does not actually exist.

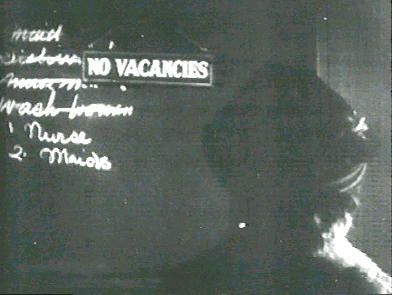

As indicated in the previous chapter with The Shamrock Handicap (1926), there is also a hint of sourness around the notion of the American dream, underlined with a title card that states ‘America. Alas for the dreams they had dreamed.’ The point is further emphasised almost immediately by indicating the lack of work available to the

mother (Fig. 7.77). Ford presents in Mother Machree (1928) the first in a long line of somewhat over-emphatic Irish characters that tended to feature in the vast majority of films he was subsequently to direct. These figures are more ‘Oirish’ than Irish, an adjective that perfectly describes the exaggerated, no-nonsense, all-knowing and somewhat devious Irish comic relief which crops up time and again in Hollywood films. To compound the stereotype, the director casts, for the first time as an Irishman, the ubiquitous stock player Victor McLaglen.[7]

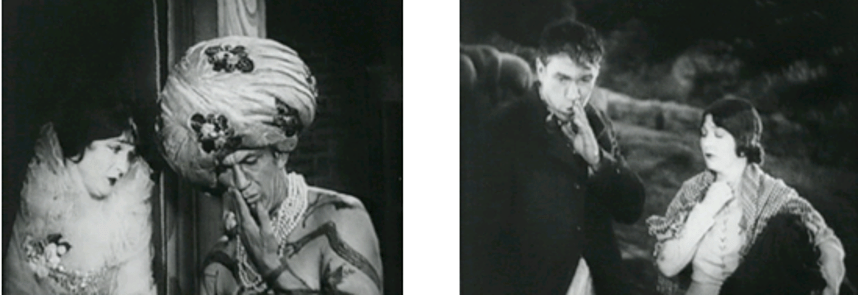

McLaglen’s character in Mother Machree (1928), the Giant of Kilkenny, is a member of a carnival troupe that meets up with the chief protagonist of the story, Ellen McHugh, first in Ireland, then America. As played by McLaglen, the

Giant is a walking compendium of Fordian gestures (Figs. 7.78 & 7.79), forever punctuating a lie by coughing behind his hand.[8] In the case of Ford’s Irish characters, there is also a tendency to indicate that a man is in deep thought by scratching the back of his head and lowering his hat over one eye, as demonstrated by Corporal Casey

in The Iron Horse (1924) (Fig. 7.80). The physical tics that these figures display are possibly due to the fact that both director and cast are working in a silent medium, and a specific posture or motion is an obvious indicator of character as well as mood, although it is also a device that Ford encourages his actors to adopt in the later sound films as well.

Despite embracing the culture of the New World, the Irish in Ford’s films retain their own identity through costume and ritual. The Giant insists on wearing a jaunty bowler and mismatched trousers and jacket, indicating his desire to

maintain his independence in a new environment (Fig. 7.81). The irony is that this costume is not necessarily what he would have worn back in Ireland, suggesting that Ford’s native Irish figures, along with Ford himself, exaggerate their own tradition and historical roots in order that their individuality as a race apart is not overwhelmed in their newly adopted land.

Although it is established at the beginning of 3 Bad Men (1926) that Dan O’Malley is of Irish descent, his ethnicity does not feature as a thematic motif throughout the rest of the film. Notwithstanding the brief tenure in Ireland of Ellen McHugh in Mother Machree (1928), Hangman’s House (1928) is therefore the first of Ford’s films to feature a native Irish person, in his homeland, as the main protagonist of the narrative. As played by Victor McLaglen, the exiled Irish patriot Citizen Hogan is portrayed as a martyr, a man who can redeem himself only by accomplishing his mission to maintain the honour of his dead sister, even though this eventually requires that he leave Ireland for good. The bars of the window through which Hogan peers pre-echo his eventual incarceration, the subtext

indicating that he will never find peace or safety in his own land (Fig. 7.82).

Once John Darcy, the villain of the piece, eventually meets his end – not at the hands of Hogan, but by an accidental fire set in motion as Darcy tries to shoot him in the back – Hogan suffers the fate that befalls other Ford figures such as Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956) and Frank Skeffington in The Last Hurrah (1958): banishment from the communal group that has no more need of their services. Despite his exile, Hogan declares in a title card that he will take ‘the green place with me in my heart’, a sentiment that echoes only too well Ford’s obvious love and admiration for the land of his forebears.

Hangman’s House (1928), along with the later films The Informer (1935) and The Plough and the Stars (1936), is one of the few times that Ford portrays his countrymen in a serious manner, eschewing a penchant for viewing the Irish as the cursory comic relief. As for Ireland itself, the director indicates yet again that it is an idyllic paradise for

its natural inhabitants, the serene countryside host to the camaraderie of community and social interaction (Fig. 7.83).

Riley the Cop (1928) is the last surviving Ford silent film to deal specifically with the Irish. In the final entry of an unofficial trilogy on Irishness that accompanies the previous titles, Mother Machree (1928) and Hangman’s House (1928), the main character is now fully assimilated into the culture of the New World. Although Riley is shown as an authority figure, he is without much power, a benign policeman confined to the lower ranks through his reluctance to actually arrest anybody.

The journey that Ford’s Irish characters make from builders of trans-continental railroads to agents of the law is

now complete; with associated gestures (Fig. 7.84) still intact. As with Hogan in Hangman’s House (1928), Ford takes the time, in Riley the Cop (1928), to present a fully rounded study of an Irish character that represents a departure from the stereotypical Irish figures that feature in his previous films. The fact that the depiction of Riley does not descend totally into farce or caricature suggests Ford is attempting to move away from the stereotype he himself helped to establish. It is significant that Riley can only really be truly Irish once he leaves the shores of America and travels to Germany, his Irish-American identity as a policeman brushed aside by a culture that momentarily allows him to rediscover his natural persona. He is not accountable to anyone but himself, and although this results in a momentary lapse into cliché, whereby Riley reverts to type and gets drunk, his professional approach to his duties as a policeman remains inviolate. This ensures that Riley, despite the physical distance between himself and his superiors, successfully completes the task at hand and extradites his prisoner back to America, his character motivated by the social code and moral authority instilled in him by his adopted homeland.

It would appear as though Ford is suggesting true happiness for any Irishman can be found only outside of America, and that somehow there is a potential for the dilution of Irishness within a new culture. Only once Riley is in a position to establish a family unit through marriage to Lena, a barmaid he meets in a German beer hall, can he call America his real home. Ireland may be referenced as the Old Country, and thus considered a wilderness compared to the modernity of the New World of America, yet the underlying theme suggests American society should be grateful that the Irish privilege the New World over any other with their presence.

Religion

Religion is integral to the portrayal of Irishness in Ford’s films. Ireland is at times depicted as an all-embracing church, in which the devout and the pious are given every opportunity to proclaim their faith through the conduit of iconographic structures conveniently placed in and around every town and village. Ford revisits the same imagery

in Mother Machree (1928)(Fig. 7.85) and Hangman’s House (1928) (Fig. 7.86), the constant use of these religious visual patterns indicating the director’s inclination to explore his own faith through his work.

The representatives of religion, particularly Catholicism, are shown as integral to the social life of the lower classes. In Mother Machree (1928), the posture of the main character, Ellen McHugh, suggests subservience towards the

priest (Fig.7.87), whilst the policemen in the background signify, in combination with the priest, the domination of law and religion over community.

By the time Mother Machree (1928) was released, Hollywood found itself under attack from various factions of the Catholic Church and the Irish-American press over the release of a film entitled The Callahans and the Murphys (George W. Hill, 1927), which was condemned by a representative of the church, Charles McMahon, as a ‘hideous defamation of the Catholic faith’ (in Walsh, 1996, p.39).[9] Subsequently, Fox and Ford were forced to toe the line when it came to the portrayal of the Irish and religion. Walsh writes that, ‘when Mother Machree (1928) was released by Fox in the following year, advertisements prominently featured letters of endorsement from leaders of the fight against The Callahans and the Murphys’ (Walsh, 1996, p.45).

The director’s late work for Fox may very well have been restricted by outside organisations such as the Catholic Church and the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). This meant that in films such as Mother Machree (1928) and Hangman’s House (1928), Irish characters and their interplay with all facets of religion within the narrative were carefully monitored by the studio. As Frank Walsh points out, although ‘there was no Catholic position on [the censorship of] films in the early years’ (Walsh, 1996, p.11), by the mid-1920s, ‘studios began to realise that they could avoid a lot of trouble and perhaps earn a place on a Catholic white list[10] by making a few simple alterations’ (Walsh, 1996, p.34).

Despite the ever-watchful eye of the Catholic Church, Ford still managed to invest his next Irish film, Hangman’s House (1928), with a certain element of cynicism towards the subject of religion. In the film, Citizen Hogan adopts the guise of a monk in order to evade capture by the British military forces. The mere fact that he wears a cowl and gown invites instantaneous deference from the faithful, and Hogan maintains the charade by constantly pointing

towards the sky, indicating a direct connection to the Almighty himself (Fig. 7.88).The religious connotation engendered by Hogan’s disguise suggests that his quest is a holy, rather than a personal, calling as he returns to Ireland to avenge the death of his sister. In placing Hogan on the outside looking in (Fig. 7.89), Ford emphasises that he is an unwelcome stranger in Ireland, and the price one pays for leaving home in the first place.

Despite organisations such as the MPPDA wielding their influence on religious content and depiction in Hollywood films of the time, it is obvious that the director’s silent Irish films provide the foundation for the successful integration of the twin themes of Irishness and religion that can be found in later titles such as The Informer (1935), The Quiet Man (1952) and The Last Hurrah (1958). Lourdeaux makes the observation that The Informer (1935), Ford’s first sound film to deal specifically with the Irish, features ‘Irish Catholic figures such as Judas and the Holy Mother’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, p.106). He further maintains that ‘the film’s most religious moment is Gypo’s final

confession […]. In the last scene, Gypo’s entrance in church begins a Passion liturgy’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, p.107) (Fig. 7.90).

McBride and Wilmington point out that The Quiet Man (1952) is also full of the ‘omnipresence of religion, […] with frequent background use of churches, stained-glass windows, church graveyards and Gaelic crosses’ (McBride and Wilmington, 1975, p.116).Lourdeaux states that, in The Last Hurrah (1958), the world of the Irish and religion converge once more, the film featuring ‘superficial glimpses into [the mayor’s] life as a Catholic, including a funeral, a confession and a death bed scene [with] his deceased wife […] virtually a stand-in for the Virgin Mary’ (Lourdeaux, 1990, p.103).

The constant references to religion in Ford’s work, either subliminal or obvious, are varied and numerous. Suffice to say that the frequent use of this motif underlines Ford’s adherence to religious tradition and evidence of the Catholic sensibility that permeates a large section of the director’s work.

Class

Tag Gallagher writes that, in the ‘1927-31 transitional phase, it is social mechanisms […] that interest Ford: any progress in characterization is coincidental, for the individual’s morality represents class consciousness’ (Gallagher, 1988, pp.60-61). Although Gallagher specifically refers to the sound films Salute (1929) and The Black Watch (1929) within this context, the class consciousness of Ford’s characters is also apparent in the late silent films prior to this. The families portrayed in films such as Mother Machree (1928) and Four Sons (1928) are all of lower class.

In the case of the former, the family are downright poor, as highlighted in the promotional material of the time (Fig. 7.91).[11]

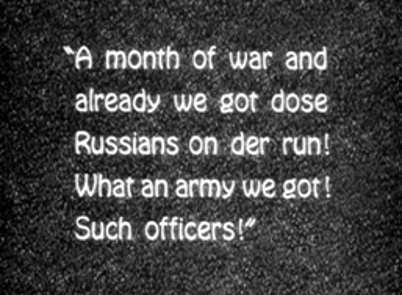

The strict hierarchical structures that operate within the armed services lend themselves very well to issues of social superiority and class, and Ford does not ignore the opportunity to explore these thematic motifs in his military films. For example, the young men who join the German army in Four Sons (1928) find themselves under the

command of the martinet Major Von Stomm (Fig. 7.92). In this instance, social and military class are one and the same, the lower ranks mere cannon fodder whilst the officers enjoy the privileges of rank. Those outside of the military are shown to be in thrall to the officer class (Fig. 7.93), with one character singing the praises of those in command, as opposed to celebrating the efforts of the common soldier.

Although Riley the Cop (1928) is a film about policemen, it could be argued that it is also aligned to Ford’s military oeuvre, as the characters inhabit a world defined by rules, regulations and uniforms. Riley is a victim of class distinction via the established military hierarchy of the police force, and constantly in conflict with his superiors. When given the opportunity to travel to Germany to extradite a wanted criminal, Riley replaces his police uniform with a dress code more in line with the landed gentry. For a short period of time, his affectation of smart dress allows him to operate outside of his lowly position within the police force, and to aspire to a more ambitious social standing. Like all of Ford’s lower class figures, however, Riley eventually abandons any pretence to leave his designated social status behind.

Of course, Ford does not solely concentrate on just the lower class in his films. Upper class characters such as the dying ‘Hanging Judge’ O’Brien in Hangman’s House (1928) epitomise the theme of corruption in men of high social standing. O’Brien insists that his daughter marry the socially acceptable yet highly disreputable John Darcy, his social position ensuring that the daughter will remain part of the privileged class. Darcy’s fate, similar to that of the villain Lane Hunter in 3 Bad Men (1926), is to be pursued by someone of a lower class, in this case Citizen Hogan, yet another Ford character out to avenge the death of a sister.

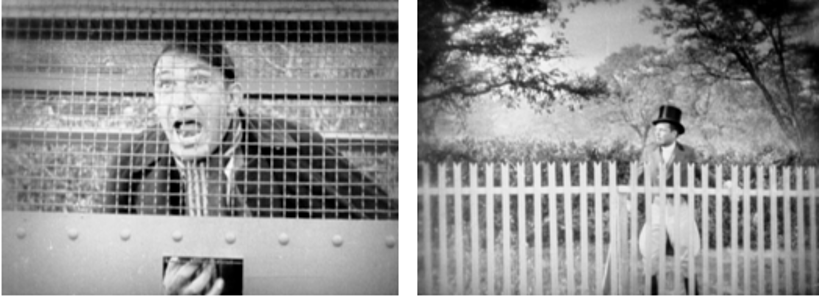

Ford’s mise-en-scène intimates that these characters are in effect imprisoned by their own position and class, with both Hogan and Darcy viewing a horse race under restricted circumstances. Hogan is arrested and incarcerated

behind a wire mesh (Fig. 7.94), whilst Darcy, although free to roam within the VIP enclosure, is literally confined by the fences that surround him (Fig. 7.95).

It is the massed crowd, penned in by their own set of fences, who threaten to break free and challenge the social

status quo (Fig. 7.96).[12] This threat becomes a reality when Darcy enrages the crowd by shooting the winning horse. The barrier between the lower and upper classes is therefore broken down not by a difference in position or authority, but by the lack of a sense of fair play on behalf of the likes of Darcy.

Social and Cultural Influences

Ethnicity

The representation of African Americans in 1920s Hollywood films, and therefore also as depicted in Ford’s late 1920s Fox films, is summarised by Cripps, who writes that,

Underlying the whole Hollywood organism was the supportive fabric of hierarchical race relations with blacks in conflict with the quiet deep-seated racial prejudices of the workers in the studio […]. The most prominent black figures viewed by whites were servants and entertainers and unctuous shoeshine boys and hustlers who clutched at the fringes of power at the studio gates. (Cripps, 1993, p.95)

In other words, the status of black Americans in films does not progress at all in the period 1927 to 1930 although, with the coming of sound, Ford is at least able to invest his black figures with more of a sense of character and screen presence than had been possible before. The Irish, on the other hand, continue to grow in prominence, to the point where they take more of a lead role in Ford’s work.

The African American actor Ely Reynolds plays a servant by the name of Deerfoot in Upstream (1927), his character somewhat less vicious than the earlier role he played for Ford as a razor-wielding hustler in The Shamrock

Handicap (1926) (Fig. 7.97). However, he is still just a cipher rather than a fully-rounded character. On a more positive note, Reynolds appears to be a member of Ford’s stock company during this period, the black actor also going on to play a small part in Riley the Cop (1928).

The black American characters in Riley the Cop (1928) are portrayed as docile and non-threatening in nature, the

children happy with their lot as they play in the streets (Fig. 7.98),or content to shine the shoes of their white

superiors (Fig. 7.99). The women are also stock characters, whether they are working maids (Fig. 7.100), or glamorous dancers (Fig. 7.101).

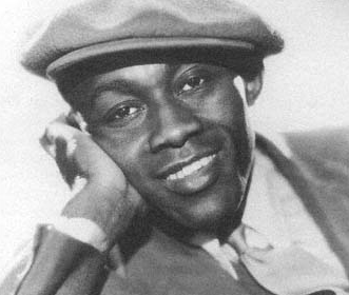

The most contentious African American member of Ford’s stock company is Lincoln Perry, known by his stage

name of Stepin Fetchit (Fig. 7.102), who appears for the first time in a Ford film in the early sound title Salute (1929). McBride supports both Ford, and Fetchit’s portrayal of the now-derided stereotypically lazy, occasionally incoherent black man, by suggesting that the director employed Fetchit ‘to ridicule and subvert the conventions of American racism’ (McBride, 2003, p.171). In this film, Fetchit is ostensibly playing the menial servant to the white Navy officers, but as the film progresses he begins to receive more screen time than any other African American character had enjoyed in previous Ford films. Fetchit is obviously the comic relief but, despite the clichédportrayal, his constant appearance throughout the film indicates Ford’s willingness to place him almost on a par with that of other supporting members of the cast, this last point reinforced by the prominence of the actor in the opening

credits (Fig. 7.103).

Tag Gallagher also defends the presence of Fetchit in Ford’s films, suggesting that the director’s aim was to satirise the commonly held belief that all African-Americans were poured from the same mould as Fetchit’s overblown characterisation. Referring to a scene in Salute (1929), Gallagher writes that, ‘short of thinking Ford a mindless racist, how else, than as satire, can one interpret the scene [in which] Fetchit (as Smoke Screen ?!) proclaims “I’se yer Mammy!”’(Gallagher, 1988, p.66).[13] Considering that the sound era was ushered in by The Jazz Singer (Alan Crosland, 1927), which features Al Jolson performing in ‘black-face’ in imitation of African American minstrels, Fetchit, albeit a questionable figure by today’s standards, was a positive step in the right direction towards the representation of ethnic minorities in film.[14]

Outside of Ford’s work, Bogle contends that, ‘for blacks in films, the talkie era proved to be a major breakthrough’ (Bogle, 2004, p.34). Citing the all-African American cast of Hearts in Dixie (Paul Sloane, 1929), which also starred Fetchit in a lead role, Bogle writes that the film ‘may not have been the best of all possible movies [but the cast] introduced an exuberance and vitality that eventually came to be associated with the American movie musical’ (Bogle, 2004, pp.35-36). According to Bogle, ‘what Fetchit’s “lazy man with a soul” ultimately did was to place the black character in the mainstream of filmic action’ (Bogle, 2004, p.57), something Fetchit arguably manages to convey in Ford’s Salute (1929) and the other later titles in which he appeared for the director.

Contemporary audiences may find the depiction of ethnicity in Ford’s films questionable. It is apparent, however, that his films, like that of all other directors, were constantly monitored at the time of release by parties dedicated to a more enlightened treatment of certain ethnic groups. For example, according to Cripps, ‘In 1937 the NAACP awarded a favourable citation to movies such as John Ford’s The Hurricane (1937) which contained anti-racist messages’ (Cripps, 1993, p.68). Cripps also goes out of his way to praise Ford’s direction of black characters in Arrowsmith (1931). In one sequence, ‘when a baby dies […] we hear wails from a circle of blacks. Potentially a cliché in other hands, Ford made it work as surely as he raised Westerns above dull routine’ (Cripps, 1993, p.300).

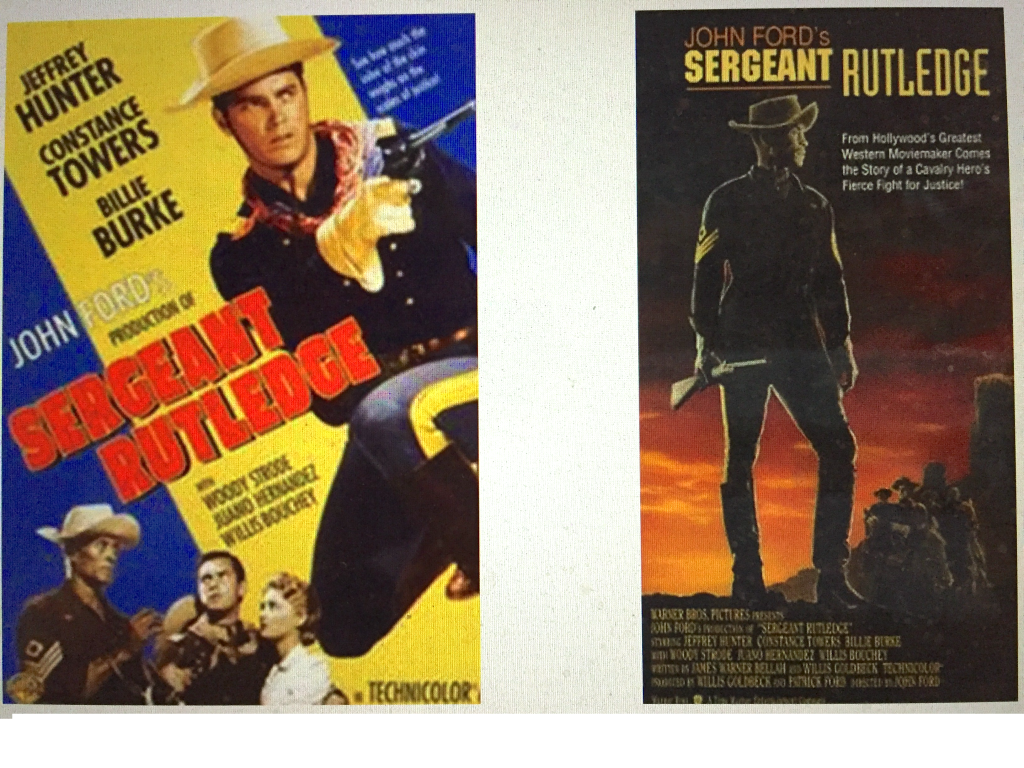

Joseph McBride affirms that the working relationship between Ford and the black actor Woody Strode, who played the title role in Sergeant Rutledge (1960), ‘demonstrated both [Ford’s] need to prove his racial enlightenment and his deep, unacknowledged ambivalence on the subject of race’ (McBride, 2003, p.608). In the film, a courtroom drama in which Rutledge is falsely accused of raping a white woman, Ford poses the actor ‘heroically against a smoke-filled sky’ (McBride, 2003, p.608) to accentuate the masculinity of his protagonist.

By privileging Rutledge with a close shot in which no other character appears (Fig. 7.104), Ford consciously underlines to the spectator the importance of this black figure within the narrative.[15] Due to the fact that in the early 60s it was unusual for a black American actor to play the lead in a Hollywood film, marketing materials

ensured that Strode was billed fourth in the cast list (Fig. 7.105), although subsequent video and DVD releases of the film now feature the actor more prominently (Fig. 7.106).

Regarding other ethnic minorities, convention and archetype continued to prevail, with some of the subsidiary German characters in Four Sons (1928) conforming to the contemporary stereotype of the time. However, Oehling includes Four Sons (1928) in a list of other silent and early sound films of the period that ‘abandoned the flat all-encompassing “hun” image of the [First World] war years, and made gestures towards individualising the Germans’ (Oehling, 1973, p.7). He also praises Ford’s film for presenting ‘an interesting mixture of positive and negative German images’(Oehling, 1973, p.9).

From the 1920s, Ford’s films embrace diverse ethnic groups such as Swedish and German, alongside the more obvious Native and African American ethnicities. In the later sound work, practically every film Ford directed had some element of ethnicity present within the narrative, from the German wrestler Polakai in Flesh (1932), through to the numerous Irish characters that pervade his work. Taking Ford’s own ethnic background into account, the Irish feature more than any other ethnic group, appearing in approximately twenty-five percent of the films he made from the 1930s onwards, either as subsidiary figures or as one or more of the main characters.

Technology

As touched upon earlier, several sequences in Upstream (1927) indicate a more adventurous approach when it comes to camera movement, grandiose sets and advanced lighting effects. This suggests a leap forward in terms of Hollywood’s aesthetic approach to filmmaking, as will be detailed in this chapter with regards not only to the films of John Ford but also to other directors of the time such as F.W. Murnau, Anthony Asquith and the Hollywood director Howard Higgin. Murnau’s Sunrise (1926) is an obvious choice of film to compare against Ford’s work when it comes to technology as both directors were employed by Fox at the same time. Anthony Asquith’s British film Underground (1927) contains a number of examples of lighting and camera movement similar to those featured in Ford films of the time such as Mother Machree 91928) and Four Sons (1928). The Racketeer (Howard Higgins, 1930) demonstrates, in line with Fords films such as Salute (1929) and The Black Watch (1929), the practical restrictions on camera mobility placed upon the director when attempting to combine sound and image at the same time.

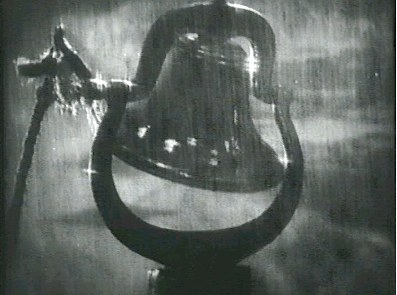

Conversely, it is the introduction of sound that pushes Ford’s work to a new level, giving not just his characters but his own vision a literal voice that lends weight to the argument that the director displayed an auteurist approach to film very early on in his career. As Tag Gallagher suggests, ‘Sound freed his characters from enslavement to intertitles, allowing them to communicate directly to the audience. And it allowed the filmmaker to dictate precisely the music and sound effects he wished. He thus had more control over an audience’s total experience during their time in the dark, and that experience became immeasurably more intense’ (Gallagher, 1988, p.54).

Cameras and Camera Mobility

Although the Bell & Howell camera equipment remained the prevalent camera of choice during the last part of the 1920s, studios occasionally resorted to using an alternative camera product, the Akeley, to film action sequences in films such as Ben Hur (Fred Niblo, 1926), Wings (William Wellman, 1927) and Hell’s Angels (Howard Hughes, 1930 but ‘its smaller 200-foot [film] magazines made it less versatile, and its images was less steady than that of either the Bell & Howell or the Mitchell […]. Mitchells and Bell & Howells remained the two standard studio cameras through the late silent period’ (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002, p.269).

The filmmakers at Fox appear to have been encouraged to utilise camera movement wherever possible in their work, Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson stating that cinematographer Charles Rosher claimed ‘to have learned the technique of the dolly suspended from tracks in the ceiling when he was observing the filming of Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1924) in Germany in 1924. He [Rosher] and Karl Struss used it to spectacular effect in the famous camera movement through the swamp in Sunrise (F.W. Murnau, 1927)’ (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002, p.229). John Ford also begins to display an affinity for camera movement, as witnessed in a number of his later 1920s films. The two long takes in Upstream (1927) do not necessarily enhance the mise-en-scène in any significant manner, but they do demonstrate technical proficiency in the use of the moving camera. The first take appears early in the film when the camera pans across the assorted boarding house residents gathered around the dining table,

introducing each of the characters to the audience one at a time, from the conceited Star Boarder (Fig. 7.107), to the dancing duo of Callahan and Callahan (Fig. 7.108). The second long take is more enterprising, following the journey of a theatre actor from a back stage door to a waiting car, before ending on a young woman who has presented the character with a bouquet of flowers. The shot runs for approximately 50 seconds and introduces the first of what is to become a series of similarly extended uninterrupted sequences that feature in Ford’s films right up until the end of the 1920s.

In the same year as Upstream (1927), the British director Anthony Asquith was employing similar moving camera shots and long takes in his film Underground (Anthony Asquith, 1927).[16] The film starts and ends with a sequence in which the camera is placed at the front of, then at the back end, of a moving underground tube train,

the images serving as a visual ‘bookend’ for the film as a whole (Figs. 7.109 & 7.110). Asquith and his cameraman, Stanley Rodwell, also incorporate a number of short tracking shots lasting no more than a couple of seconds before

moving on to a longer uninterrupted take that lasts for approximately 16 seconds (Figs. 7.111 & 7.112). These moving shots culminate towards the end of the film in a 40 second tracking shot that starts by following a woman running

(Fig. 7.113) before finally settling ending up on a low-angle shot of a power station (Fig. 7.114). As with numerous other directors of the time, the examples of mobile camera sequences in Ford’s work indicates how he is developing as a director by engaging with the evolution of film language.

As well as the opening tracking shot referred to earlier in this chapter, Four Sons (1928) features two more examples of the long take, but this time camera mobility is used as a device to evoke atmosphere and emotion. The first instance presents the camera moving backwards, parallel to a train entering the village station. At the

beginning of the take the characters shown comprise the inhabitants of the village (Fig. 7.115), starting with the station-master. By the finish, the kindly and peaceful villagers are replaced by the military, with the extended shot encompassing the end of peacetime and the imminence of war in one take (Fig. 7.116).

In a later sequence featuring a long take that runs for almost 50 seconds, the camera follows an American soldier across a field in the aftermath of battle. The darkness surrounding the edge of the image combines with the mist-laden mise-en-scène to signify the moment of transition from life to death, an event emphasised at the end of the (Howard Higgin, 1930) (Fig. 7.132) appear to be more in keeping with the style of studio lighting as described in Mother Machree (1928).

take when the soldier comes across his dying brother (Figs. 7.117 & 7.118), who has fought on the opposing side.

Hangman’s House (1928) features three tracking shots of varying length, one as short as 18 seconds, with the other two approximately half a minute in length. At times, the images are invested with touches of fog and mist to

suggest elements of mystery and obfuscation of character. For example, Citizen Hogan, disguised as a monk (Fig. 7.119), makes his way through a shrouded landscape, accompanied by swirling clouds of fog that practically obscures the background scenery. Later on, two men arrange a clandestine meeting, the secrecy of their conduct

strengthened by a mise-en-scène similar to the previous take featuring Hogan as a holy man (Fig. 7.120). The two lovers, Connaught and Dermott, also collude in secret, undertaking a boat trip to meet with Hogan (Fig. 7.121), while the camera follows their languid trip through yet another vista cloaked in fog. All of these long takes are accomplished within a studio setting, enabling Ford and his cinematographer, George Schneidermann, not only to move the camera in a controlled environment, but also to enhance the imagery, where required, with the elements of fog and mist that suggest the furtive nature of the characters. Although the mist and the darkness combine to suggest an air of mystery within the mise-en-scène, it is the uninterrupted movement of the camera that successfully conveys a mood of apprehension.

Although still studio-bound, Ford’s use of prolonged camera movement on the back lot in Riley the Cop (1928) is slightly more adventurous than previous examples. In the first of only two long takes in this film, the camera starts with the projected shadow of Riley, before following the policeman as he patrols his neighbourhood beat. This and the other extended take, in which Riley encounters his bride-to-be for the first time, are both brightly lit and bathed

in natural sunlight, with the mise-en-scène reflecting the tone and disposition of both character and story (Figs. 7.122 & 7.123).

By the end of the decade the movement of the camera was severely compromised by the requirement to distance the equipment from the sound machines that ushered in the ‘talkies’. According to Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, the immediate result of the introduction of sound was the adoption of multiple-camera filming which struck a compromise between the technical necessity of sound and the filmmaking style of the silent era (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 202, p.305). An example of a multiple-camera sequence can be found in the early sound film The

Racketeer (Howard Higgin, 1930), in which two cameras film the action from different angles (Figs. 7.124 & 7.125), facilitating a smooth transition in the scene without the requirement to stop filming and redirect both the actors and the sound equipment.

Towards the end of the silent period, the increasing confidence with which Ford and his various cameramen embrace the technology of the moving camera eventually leads to the point where the mobile shot, whether it is a long or a short take, resides seamlessly within the fabric of the film. However, these extended sequences eventually lose their early novelty value as far as Ford is concerned, although they remain integral to the evolution of film language. Despite the occasional use of a mobile shot, it is obvious from looking at the later Ford films that there is a dearth of long takes, leading to the conclusion he was not particularly enamoured of the technique. In short, this type of shot never fully evolved as an intrinsic component of the director’s style.

Lighting

According to Salt, by the mid 1920s, there was a ‘swing to using incandescent tungsten lighting [but it] made no appreciable difference to the style of film lighting’ (Salt, 1983, pp.222-223). If Salt is correct then the change in the look and style of Ford’s films towards the end of the silent period seems to be more of an aesthetic choice, rather than a decision influenced by advances in lighting technology. The use of lighting in Upstream (1927) to illustrate

the staging of Hamlet is a case in point (Fig. 7.126), with the stage bathed in an atmospheric combination of shadow and muted back light that conjures up the spirit of the famous graveyard scene. The sequence that follows appears to be one of the most complicated lighting arrangements seen in a Ford film up until this point in time (Fig. 7.127). It incorporates what looks to be four separate points of light, including the backlighting that illuminates the audience, the bright footlight in front of the actor on stage, and the two lights front of stage, behind the curtain, and

behind the scenery. In comparison, a scene very similar to this can be found in The Racketeer (Howard Higgin, 1930) (Fig. 7.128), in which the lighting style is far more muted. Ford on the other hand shows ambition in Upstream (1927) and an evolution previously missing from his work.

The lighting for the storm sequence that takes place towards the beginning of Mother Machree (1928), in which the intricate use of separate sources of light pinpoints specific elements of the mise-en-scène, also demonstrates

that Ford’s work is evolving towards a more complex use and application of lighting techniques (Figs. 7.129 & 7.130).

Asquith incorporates a similar approach in accentuating light and shadow in his film Underground (Anthony Asquith, 1927), (Fig. 7.131), the resultant mise-en-scène echoing the expressionistic style of 1920s films such as

Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927) and Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922), although the illumination in some of the scenes from The Racketeer (Howard Higgin, 1930) (Fig. 7.132) appear to be more in keeping with the style of studio lighting utilised in Mother Machree (1928).

Building on the atmospheric style of Mother Machree (1928), and the influence of Murnau, Ford applies multiple sources of light in Four Sons (1928) to create a starkly vivid image suggestive of a framed painting. The light in the background, combined with another source from screen right, highlights the lone figure of a mother wilting after the

loss of her sons in battle (Fig. 7.133). The composition of the image, particularly one in which there is a total lack of movement, reinforces Eyman and Duncan’s suggestion that Ford’s silent work indicated a conscious attempt to emulate the aesthetic of a still painting. The influence of Whistler, rather than Remington, appears to be more

relevant in this particular example, the obvious reference point being the famous portrait of the artist’s mother (Fig. 7.134).

The effect of religion upon the evolution of Ford’s style has already been touched upon in this and previous chapters. What has yet to be considered is the way in which the numerous images relating to religion in Ford’s films owe a great deal to the lighting techniques applied within the mise-en-scène. In Four Sons (1928), two nuns pray outside the house of the grieving mother, with the application of a single source of light suggesting the presence of an off-screen omniscient entity. The mask on the lens blurs the outer edge of the image, and only the house and

the figures outside are captured within the glow of light apparently emanating from the sky (Fig. 7.135). In another shot, the front of a church is bathed in an almost heavenly light, stressing the hallowed nature of the building (Fig. 7.136). Where this differs slightly from the previous example is in the presence of a light in the background to illuminate the inside of the church, thus clarifying the depth of field within the image.