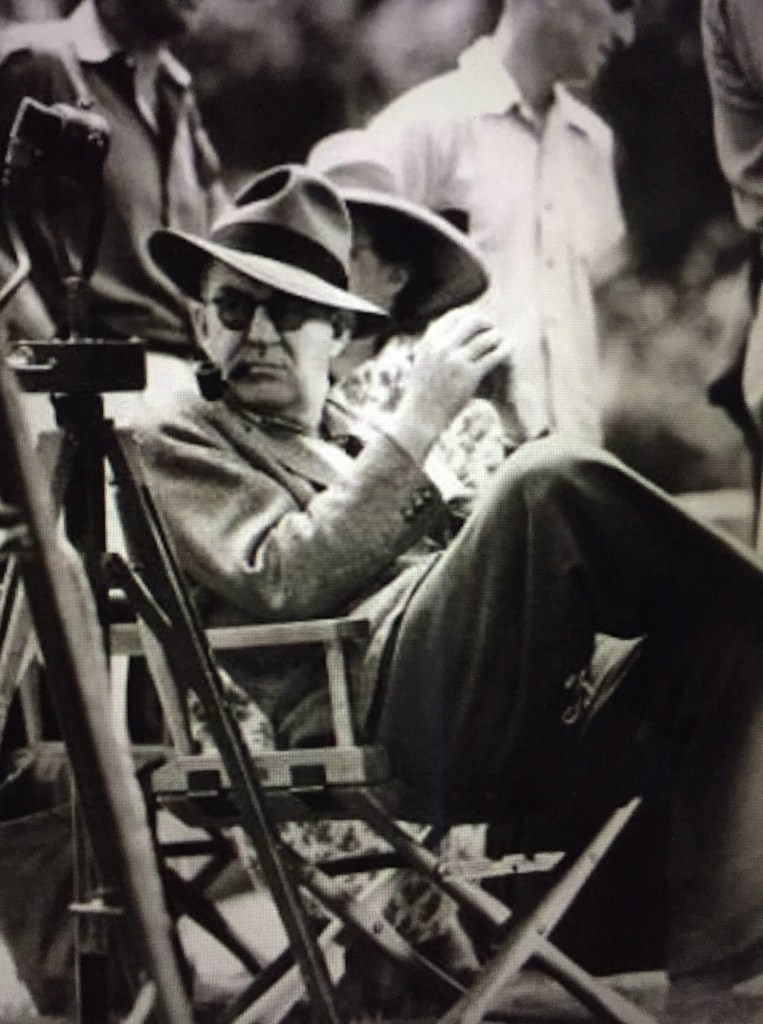

In the numerous articles written on the auteur theory since the early 1950s, John Ford is often referenced as an example of the concept. In his seminal essay, ‘Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962’, Andrew Sarris mentions Ford in the very first paragraph (Sarris, 1985, p.527). Peter Wollen gives equal consideration to both Ford and Howard Hawks in the chapter on the auteur theory from his book, Signs and Meaning in the Cinema(Wollen, 1987, pp.94-102). Seven of the essays published collectively in Theories of Authorship, edited by John Caughie, are listed under the heading ‘Dossier on John Ford’. A casual student of film could therefore not be blamed for thinking that Ford is the quintessential auteur, virtually synonymous with the concept of authorship; but of course, the truth is more complex

For example, the role of a director as sole auteur is complicated by the contribution of the various scriptwriters with whom he or she may have worked. In Ford’s case, a large proportion of his output was written by three writers, George Hively, Dudley Nichols and Frank Nugent. Should they also be given credit as authors of, respectively, Bucking Broadway (1917), The Informer (1935), and The Searchers (1956)? On the other hand, a close examination of Ford’s films reveals a number of consistent thematic motifs present in most of the titles he directed from 1917 to 1966, irrespective of whoever wrote the script. This suggests that Ford’s interpretation of each individual screenplay transcended their differences, lending his films an overarching coherence and an identifiable ‘personal vision’, whatever the date, genre or collaborator. For example, The Hurricane (1937), with a scenario written by Dudley Nichols, is as much a consideration of the fracturing of the family unit as is The Searchers (1956), scripted by Frank Nugent. That in itself does not necessarily mean that Ford was able to express his personal vision directly within each film, as a novelist might with a work of literature. Certain other factors must be taken into account, such as the constraints imposed by working within the Hollywood studio system. In using Ford as a case study on the question and nature of authorship, one must also consider, along with the aforementioned influences, the effect of other factors such as technological innovation and contemporary social attitudes. The following chapters engage in depth with each of these issues but, as even this brief discussion demonstrates, a range of external influences and surrounding frameworks – institutional, cultural, technological and biographical – must be taken into account before we can assess the various factors that constitute Ford’s authorship of his films. That is, though we can agree with the existing body of scholarship that Ford is an auteur, the next and most important step is to examine exactly what that means, within the specific medium and context of classical genre cinema during the years 1917 to 1930.

The other complication which arises when attempting an auteurist study of a director’s body of work is that the theory itself has been through various stages of evolution and development. As Will Brooker points out, ‘the figure of the author as an individual who governs the sole meaning of a text has been subject to significant challenges within the academic debates of the last fifty years’ (Brooker, 2012, p.3). Since Cahiers du Cinéma started to champion the auteur theory in the early 1950s, it has undergone a number of changes, encompassing along the way theoretical concepts such as structuralism, and initiating a lively discourse on how authorship is shaped through other influences, such as cultural and institutional factors, that mould and define a director’s sensibility and its expression.

This chapter offers a short history of the genesis, evolution and subsequent complexities of the auteur theory, or, as it was originally known, la politique des auteurs, a term covered in more detail further on. This broader discussion of the fundamental debates around ‘authorship’ will build into a more specific exploration of Ford and the ‘Fordian sensibility’, drawing on the work of scholars Charles Silver, Peter Wollen, Scott Eyman and Peter Duncan, and on my own research from close primary study of the director’s work.

This preliminary examination of both auteurism and the concept of the ‘Fordian’, serves as the foundation for the later chapters of this thesis.

Pre-Auteur Theory

Robert Stam points out that ‘already in 1921, the filmmaker Jean Epstein used the term “author” to apply to filmmakers’ (Stam and Miller, 2000, p.1). Stephen Crofts confirms that proto-auteurism, the ‘forerunner of auteurism, emerges sporadically in European film reviewing and criticism from the 1920s onwards’, going on to assert that this approach ‘restricts itself to directors who empirically possessed more creative freedom than most within Hollywood’ (Crofts, 1998, p.312). These comments are borne out by the film scholar and critic Paul Rotha, whom Crofts mentions along with other proto-auteurists such as the avant-garde film director Louis Delluc and the British director Lindsay Anderson.

Writing in his book The Film Till Now, first published in 1930, Rotha states that directors such as Griffith, Stroheim and Chaplin ‘would in all probability make fuller use of their abilities if they were not entangled in the structure of the studio system’ (Rotha, 1967, p.189). He maintains that with regards to directors such as King Vidor and Josef von Sternberg, ‘in much of their work is an idea, an experiment, a sense of vision, a use of the camera, a striving after something that is cinema, which is worth detailed analysis for its aesthetic value’ (Rotha, 1967, p.189). Rotha attempted to articulate the case for a more studied analysis of the question of film authorship but confined this to a group of the more well-known and successful of the contemporary Hollywood directors.

In assessing the serious analysis of film prior to the development of the auteur theory, one cannot underestimate the importance of André Bazin, eventual co-creator with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca in 1951 of Cahiers du Cinéma and the ‘spiritual father of the New Wave’ (Matthews, 1999, p.24). Prior to his involvement in the development of the auteur theory in the early 1950s, Bazin explored a form of proto- authorship. Donato Totaro states that in the 1940s Bazin employed ‘a stylistic and semi-auteur approach’ in which ‘he groups all directors between the years 1920 to 1940 into two groups: one which base their integrity in the image (the imagists) and another which base their integrity in reality (the realists)’ (Totaro, 2003, p.3). In fact, Bazin was already using the term auteur in the 1940s in reference to the influence of the director on mise-en-scène and narrative. In his 1948 essay ‘William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing’, Bazin praises Wyler’s cinematic purity, stating that, ‘not once has the auteur of The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946) or Jezebel (William Wyler, 1939) said to himself a priori that he had to have a “cinematic look”; still, nobody can tell a story in cinematic terms better than he’ (in Piette and Cardullo, 1997, p.18). The proto-auteurist critic, as personified by Bazin, had the intellectual and critical ability to consider the analysis of films in specific auteurist terms. However, as discussed later in this chapter, it took the liberation of France from the occupying German forces and the subsequent fall of the Vichy government to provide the catalyst that allowed the theory of authorship to flower and take shape.

Auteur Theory – The 1950s

Of all the critics and writers associated with the early 1950s publication of Cahiers du Cinéma, it is François Truffaut who is generally acknowledged as being the first of his group to officially articulate the relevance of la politique des auteurs. Commenting on the subject of the difference between la politique des auteurs and what eventually came to be referred to as the auteur theory, Andrew Tudor writes,

How ‘policy’, the most obvious translation of ‘politique’, became a ‘theory’ is a tributary in the history of ideas which need not be dealt with here. Sufficient to note that when the Cahiers group said ‘policy’, they meant ‘policy’. Their use of auteur was exactly that: a polemical position marking their views off from the orthodox tradition in French criticism and, ultimately, when they started making films, from the rest of French cinema. (Tudor, 1974, pp.121-122)

A closer inspection on the evolution of the hypothesis put forward by Truffaut and his colleagues reveals that no one individual can be singled out as the sole architect of the auteur theory. For example, John Caughie points out that although Truffaut’s 1954 article in the issue no. 31 of the magazine, ‘Une certaine tendance du cinéma francais’ (‘A certain tendency of the French cinema’), ‘threw down the gauntlet of “la politiques des auteurs”’, it did not ‘invent the idea of auteurism’ (Caughie, 1993, p.35). British film writer Peter Wollen suggests that the auteur theory ‘was developed by a loosely knit group of critics’ (Wollen, 1987, p.74), maintaining that the theory ‘grew up rather haphazardly; it was never elaborated in programmatic terms, in a manifesto or collective statement’ (Wollen, 1987, p.77).

The basic contention of the theory itself is that certain films reflect the personal creative vision of the director, elevating the director to the status of author, or ‘auteur’, of the work as a whole. In effect the theory is a validation of Hollywood films, previously thought not to be worthy of serious critical evaluation. As Edward Buscombe comments in his essay, ‘Ideas of Authorship’, ‘Cahiers was concerned to raise not only the status of the cinema in general, but of American cinema in particular, by elevating its directors to the ranks of the artists’ (Buscombe, 1993, p.23). Truffaut and his colleagues were reacting to the staid and sterile post-war cinéma de qualité (‘quality films’) of directors such as ‘Delannoy, Allégret and Autant-Lara’ (Buscombe, 1993, p.23), Robert Stam contending that they were ‘dynamiting a place for themselves by attacking the established cinema, derisively labelled the cinéma de papa (“Dad’s cinema”)’ (Stam and Miller, 2000, p.3).

According to both Crofts and Wollen, a key critical factor in the development of auteurism was the fact that the huge influx of Hollywood films released into France after the Liberation, along with a thriving ciné-club movement, combined to create an atmosphere in which the auteur theory could flourish. Wollen maintains that the policy of the archivist and co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française, Henri Langlois, to show as many of the American films previously unreleased in France during the German occupation as he could at the Paris Cinémathèque, gave ‘French cinéphiles an unmatched perception of the historical dimensions of Hollywood and the careers of individual directors’ (Wollen, 1987, pp.74-77). Critics were thus given the opportunity to view, over a short period of time, previously unseen films by directors such as Hawks, Ford and Hitchcock. If one takes Ford as an example this means the almost simultaneous release in France in 1946 of Stagecoach (1939), Young Mr Lincoln (1939), Drums Along The Mohawk(1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Long Voyage Home (1940), Tobacco Road (1941), How Green Was My Valley(1941), They Were Expendable (1945) and My Darling Clementine (1946), a formidable body of work by any standard and a unique opportunity for the spectator to discern the key themes, narrative traits and visual and thematic motifs that reside in Ford’s work.

The theory was not used merely to celebrate everything Hollywood had to offer. As Buscombe usefully points out, ‘Bazin distinguishes between Hitchcock, a true auteur, and Huston, who is only a metteur en scène […]. Huston merely adapts, […] instead of transforming it into something genuinely his own’ (Buscombe, 1993, pp.23-24). In fact, whilst Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol and the other Cahiers acolytes feverishly raced to outdo each other in their bid to consecrate those Hollywood directors barely known outside America, such as Edward Ulmer, Delmer Daves, Richard Brooks and Edward Dmytryk, it was Bazin who first started to question the nature of a theory that exclusively focused on the director without taking into account the commercial and industrial process from which most Hollywood films were constructed. Breaking ranks in 1957 with his essay ‘La politique des auteurs’, Bazin stated that ‘the American cinema is a classical art, but why not then admire in it what is most admirable, not only the talent of this or that film-maker, but the genius of the system?’ (in Caughie, 1993, pp.45-46). In fact, Bazin’s observation informs the approach the thesis adopts in examining Ford’s status as auteur by taking into account the influence that working within the studio system had upon the development of the director’s style.

Auteur Theory – The 1960s and Beyond

Kent Jones credits Andrew Sarris with introducing his version of the auteur theory to America, stating that ‘it was Sarris who took it upon himself to overhaul American film criticism’, taking ‘a post-war French idea – the politique des auteurs – and translating it as the auteur theory’ (Jones, 2005, p.2). In his seminal 1962 essay, ‘Notes on the AuteurTheory’, Sarris ‘gives the Cahiers critics full credit for the original formulation of an idea that reshaped my thinking on the cinema’ (Sarris, 1985, p.536). Sarris contends that ‘the first premise of the auteur theory is the technical competence of a director as a criterion of value [and] the second premise […] is the distinguishable personality of the director as a criterion of value’ (Sarris, 1985, p.537). He goes on to state that ‘the third and ultimate premise of the auteur theory is concerned with interior meaning’ (Sarris, 1985, p.538).

Pauline Kael responded to this last premise in her 1963 article, ‘Circles and Squares’, by asking ‘is “internal meaning” any different from “meaning?”’ (Kael, 1985), thus initiating a war of words between herself and Sarris’ interpretation of the auteur theory. Whilst ‘Sarris responded to Kael, reasserting his position that auteurism was a valuable method for studying film history’ (Gerstner and Staiger, 2003, pp.38-39), Kael was moved in 1971 to write The Citizen Kane Book, devoted to the ‘refutation that the director alone was the auteur of a film’ (Cook, 1985, p.137). Edward Buscombe also joined in the debate a few years later, pointing out that Sarris had misinterpreted both the term and the meaning of la politique des auteurs. Buscombe stated that, ‘Not only was the original politique of Cahiers somewhat less than a theory; it was itself only loosely based upon a theoretical approach to the cinema which was never made fully explicit’ (Buscombe, 1993, p.22).

However Sarris interpreted la politique des auteurs, it provided the opportunity to legitimately view the films of John Ford, for instance, as the work of an artist (albeit within a collaborative medium) rather than a mere purveyor of commercial product. Sarris is also flexible enough not just to consider Ford’s work in terms of authorship, stating in his book The John Ford Mystery that Ford can be ‘very profitably studied before 1930 in terms of studio policy’ (Sarris, 1975, p.34), another approach adopted in the thesis when researching Ford’s silent film work.

Sarris went on to legitimise certain film-makers whom he felt displayed a personal vision in their work by placing them in what he dubbed a Pantheon of Directors. The usual suspects such as Hawks, Ford and Welles were firmly ensconced at the top of the list. Fred Camper notes that other directors not deemed worthy of the Pantheon were listed in various other categories such as ‘The Far Side of Paradise, Strained Seriousness (uneven directors with the mortal sin of pretentiousness) and Subjects for Further Research’ (Camper, 2007, p.1).

At the same time as Sarris was adapting la politique des auteurs as a means to validate his pantheon of directors, British film criticism also turned its attention to the auteur theory through the film magazine Movie and contributors such as Ian Cameron, Mark Shivas and Victor Perkins. According to John Caughie, ‘Movie shared with Cahiers the general principle that the director was central to the work’, going on to suggest that both publications ‘shared close attention to the mise-en-scène’ (Caughie, 1993, p.48). Pam Cook suggests that, prior to British film criticism embracing the auteur theory, members of the Free Cinema Movement such as film-makers Lindsay Anderson and Karel Reisz subscribed to the ‘idea of “personal vision” which was at the root of the politique des auteurs but without its emphasis on popular American cinema’ (Cook, 1985, p.147).

Ian Cameron championed the relevance of the auteur theory to American cinema, writing in his 1962 essay, ‘Films, Directors and Critics’, that ‘the closer one looks at Hollywood films, the less they seem to be accidents’ (in Caughie, 1993, p.53). Cook points out that the championing by Movie contributors of ‘the auteur theory and popular Hollywood cinema had far-reaching effects on British film criticism’ (Cook, 1985, p.147). She further points out that the ensuing debate on the theory contributed towards the adoption of film studies ‘as a serious object of study on the level of other arts such as literature and music’ (Cook, 1985, p.147).

The next step in the evolution of the theory occurred in the late 60s with the introduction of structuralism into the equation. Stephen Crofts defines auteur-structuralism as a ‘kind of shotgun marriage very much of its moment’, going on to state that this new variant on the auteur theory ‘employed a theoretical sophistication and analytical substance lacking in auteurism’ (Crofts, 1998, p.315). Crofts suggests that it was film theorist Peter Wollen in his influential 1969 book, Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, who crystallised the adoption of a structuralist approach to the analysis of a director’s oeuvre.

In defining auteur-structuralism, Wollen first of all uses the work of Howard Hawks and John Ford to outline his own position on auteurism, suggesting that what the ‘theory does is to take a group of films – the work of one director – and analyse their structure’ (Wollen, 1987, p.104). He then goes on to suggest that Ford’s films are replete with what he calls ‘antimonies’, pairs of opposites such as ‘garden versus wilderness, plough-share versus sabre, […] book versus gun, […] East versus West’ (Wollen, 1987, p.94), maintaining that a structural analysis of Ford’s work reveals the ‘richness of the shifting relations between antimonies [that] makes him a great artist’ (Wollen, 1987, p.102). Taking the first category as an example, Wollen cites the films The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), The Searchers (1956), Wagon Master (1950) and My Darling Clementine (1946) as evidence of Ford’s interest in the twin themes of garden and wilderness. However, we could note that the application of this antimony is not restricted just to Ford’s Westerns. One might argue that The Grapes of Wrath (1940) has an underlying theme of the garden returning to wilderness in the Depression era, and The Hurricane (1937) depicts a South Pacific Garden of Eden destroyed by nature and reduced to wilderness. Wollen also writes that the structural analysis of a director’s work initiates the elevation of the film-maker almost to a brand name, stating that ‘Fuller, or Hawks or Hitchcock, the directors, are quite separate from “Fuller” or “Hawks” or “Hitchcock”, the structures named after them’ (Wollen, 1987, p.168). Applying the same concept to John Ford, the thesis examines the manner in which the director evolves into a brand known as ‘John Ford’, an entity quite separate from Ford, the named director.

In the same year that Wollen’s book was first published, the French philosopher Michel Foucault also proposed, in his essay ‘What is an Author?’, the view that ‘an author’s name is not simply an element in a discourse’ (Foucault, 1984, p.107). Foucault argues that,

The author’s name, unlike other proper names, does not pass from the interior of a discourse to the real and exterior individual who produced it; instead the name seems always to be present, marking off the edges of the text […]. The author’s name […] has no legal status, nor is it located in the fiction of the work […]. The author function is therefore characteristic of the mode of existence, circulation, and functioning of certain discourses within a society. (Foucault, 1984, pp.107-108)

Foucault’s hypothesis is to suggest, in the case of Ford for example, that in studying the work of the director, one can differentiate between the man and person known as John Ford, and the discourses and texts that emanate from the body of work that, for want of a better phrase, may be labelled Fordian. This distinction between the man known as John Ford and the brand ‘John Ford’ informs the subsequent discussion, in later chapters, of the relationship between Ford’s personal background and biography, and his creative oeuvre.

Not all British film critics subscribed to Wollen’s concept of auteur-structuralism. Robin Wood berated Wollen for the way in which the use of ‘the Structuralist heresy’ (Wood, 1993, p.98) allowed Wollen to evade questions raised through a more traditional auteurist approach to one of Ford’s later – and more problematic – films, Donovan’s Reef (1963). The frank and open exchange of views that were traded between certain members of the British film writing community mirrored at times the aggressive difference of opinion exhibited by Pauline Kael towards the writings of Andrew Sarris. Lindsay Anderson, champion of Ford and a firm advocate of the ‘personal vision’ strand of the auteur theory, specifically went out of his way to berate Wollen’s critical approach in his book, About John Ford. Anderson complains that ‘in recent years film criticism has lost its proper sense of purpose’ (Anderson, 1981, p.11). Citing an extract from Signs and Meaning in the Cinema in which Wollen writes ‘there will be a kind of torsion within the permutation group, within the matrix, in which some antimonies are foregrounded’ (in Anderson, 1981, p.11), Anderson is moved to remark that ‘this is film criticism busily engaged in disappearing up its own backside’ (Anderson, 1981, p.11).

Brian Henderson, in his 1973 article, ‘Critiques of cine-structuralism’, delivered a more measured coup de grâce to Wollen’s defence of auteur-structuralism. Henderson maintains that ‘auteur-structuralist texts speak for themselves and in speaking, through their gaps, omissions, and contradictions, destroy themselves’ (Henderson, 1993, p.175). He further questions Wollen’s attempt to ‘merge auteurism with structuralism without altering either in the process’ (Henderson, 1993, p.176), calling into question the contradictory nature of the theory itself. Henderson’s demolition of the auteur-structuralist mode of analysis served to curtail the application of Wollen’s hybrid theory in the burgeoning field of film studies. Interesting though the structuralist approach may be, an overview of the way in which the auteur theory has evolved since the mid-1980s up until now leaves one to conclude that it remains more of a diversion than a true evolutionary step in the history of the theory itself.

By the mid-1980s the auteur theory was truly ensconced as a valid critical tool for students of film studies. Exam papers of the time tended to focus on the more well-known directors such as Hawks, Hitchcock and Bergman, one of the questions on the auteur in the 1986 Film Studies A2 paper, ‘Douglas Sirk has been described as a progressive auteur. What do you think is meant by this?’(Welsh Joint Education Committee), inherently acknowledging the Sarris view of pantheon directors. At the same time the questions would also implicitly reference the prevailing influence of the Cahiers contingent. For instance, over thirty years after Bazin categorised John Huston as ‘only a metteur en scène’, the same 1986 paper suggests that, ‘the intimate scenes in Huston’s films are often staged as if he were playing snooker with a sledge hammer. Do you agree?’ (Welsh Joint Education Committee, 1986).

During the 1980s, outside of film studies, the auteur theory appears to have been somewhat disregarded by serious film critics and writers, prompting the American film scholar J. Dudley Andrew in his 1993 article, ‘The Unauthorised Auteur Today’, to eventually rejoice that ‘after a dozen years of clandestine whispering we are permitted to mention, even discuss, the auteur again’ (Stam, 2000, p.21). A few years before, in 1990, the American film critic James Naremore suggested in his article ‘Authorship and Cultural Politics’ that, ‘auteurism is dead, but so are debates over the death of the author’ (Boschi and Manzoli, 2007, p.1). The dialogue around authorship in cinema is, we can therefore assume, ongoing and inconclusive. It therefore comes as no surprise that in recent years the auteur theory has evolved to a point where it now encompasses and encourages numerous strands of hybrid discourse. As Stephen Crofts points out, ‘discourses of authorship have emerged across the whole gamut of cinematic institutions from film production through film reviewing, criticism and analysis, to film history and theory’ (Crofts, 1998, p.310).

Crofts identifies modes of authorship that combine the concept of director as author with, for example, production institutions, social subject and politics or pleasure. A number of these modes are highly relevant in terms of a critical approach to the films of John Ford. For instance, the mode Crofts refers to as ‘author in production institutions’ (Crofts, 1998, p.320) affords the opportunity to analyse Ford’s silent films as products of the early Hollywood industrial system, specifically that of the Universal and Fox Corporation studios. Other modes of authorship would also appear to be relevant to the critical analysis of Ford, as Crofts specifically relates the Cahiers du Cinéma 1970 assessment of the director’s Young Mr Lincoln (1939) to the category of ‘author as instance of politics and / or pleasure’ (Crofts, 1998, p.316).

Asking the question, ‘Why does the notion of authorship persist so strongly?’, Crofts confirms that the auteur theory ‘still has enormous influence within cultural discourse’ (Crofts, 1998, p.322). One recent example of this discourse in action is the 2006 article by Alexander Hicks and Velina Petrova, ‘Auteur Discourse and the Cultural Consecration of American Films’. Citing the Allen and Lincoln 2004 study of the 1990s consecration of American films by the American Film Institute, Hicks and Petrova maintain that Allen and Lincoln ‘invoke a function for auteur theory within film discourse that they do not much investigate’ (Hicks and Petrova, 2006, p.181). Making the link between the director as auteur and the critics who bestow auteur status on the film-maker, Hicks and Petrova state ‘that direction by an auteur emerges as a cause of a film’s retrospective consecration’, concluding that the ‘influence of auteur directors on film consecration highlights the importance for this consecration of critics who actually create and apply theories like auteur theory’ (Hicks and Petrova, 2006, pp.181-182).

A recent and healthy debate such as this implies that the auteur theory is very much a subject for discussion more than fifty years after Truffaut and Cahiers promoted the concept of the director as author. Outside of the field of film studies the term auteur is now a common expression, used by mainstream film critics and popular film magazines alike; the term is no longer confined to the more esoteric and academic literary world of the film scholar and critic.

When it comes to contemporary auteur studies, as Robert Stam points out, ‘the romantic individualist baggage of auteurism has been jettisoned to emphasize the ways a director’s work can be both personal and mediated by extrapersonal elements such as genre, technology (and) studios’ (Stam, 2000, p.6). As for the future, the theory still has potential to develop in a number of different directions. Stam also suggests one of the main strengths of the theory is that ‘auteurism has performed an invaluable rescue operation for neglected films and genres. It rescued entire genres – the thriller, the Western, the horror film – from literary high-art prejudice’ (Stam, 2006, p.6).

As for the future, the theory still has potential to develop in a number of different directions. For instance, as far back as 1969, Wollen suggested that the theory could evolve by comparing the auteur as director with ‘authors in the other arts: Ford with Fennimore Cooper, for example, or Hawks with Faulkner’ (Wollen, 1987, p.115). The thesis follows this approach by highlighting the images captured by nineteenth-century painters of the West, comparing Ford’s work with artists such as Frederic Remington and Charles Schreyvogel. The producer as auteur is already prevalent, and one might argue that the writer as auteur is equally as meaningful. No matter how the theory may evolve, the ongoing debates and the fragmentation of the auteur theory into various distinct and hybrid modes continues to provide a powerful method of identifying consistency of style and theme in a body of work when approaching a director’s oeuvre; this traditional auteurist approach, as practised for instance by Sarris in 1962, remains a useful method when analysing the films of John Ford.

The ‘Fordian Sensibility’

Charles Silver maintains that it was not until Ford made Steamboat ‘Round the Bend (1935) that the director could truly be called an artist. This final entry in the trilogy of films made with Will Rogers in the 1930s marked ‘a turning point [in the director’s career], for it has a fullness and diversity his earlier films lacked’ (Silver, 1974, p.67). Silver further states that, taking a cue from Griffith and Murnau in particular, Ford wove ‘these two together into a classicism and genius of his own. Not only had he grown out, but he had grown up’ (Silver, 1974, p.67).

In order to determine how Ford eventually integrated this successful combination of commercial filmmaking with his own personal artistry and expression, the thesis studies the director’s surviving silent films in close detail to discern the origins and evolution of his distinctive motifs and themes. As Jeffrey Richards points out in his article, ‘The Silent Films of John Ford’, ‘the rediscovery of many of Ford’s silent movies has enabled film historians to trace a visual, stylistic and thematic coherence and continuity with the director’s later and more familiar work’ (Richards, 1981, p.2345).

In their 2004 book, John Ford: The Complete Films, Scott Eyman and Peter Duncan compiled a list of Fordian motifs. Taking the observations of both Wollen, Eyman and Duncan into account, it is possible to present a more definitive list of the thematic and visual motifs that contribute towards a sensibility and aesthetic which can be characterised as identifiably Fordian in content and application:

- Integration into society

- Outsider as man of action

- Self-sacrifice

- Religion

- Ethnicity

- Irishness

- Mother figure and mother love

- Civilisation versus wilderness

- Past versus modernity

- Community

- The Promised Land

- Conversing with the dead

- Nostalgia for the South

- Military honour

- Disintegration of family

- Cynicism towards authority

- Ritual: Eating, music and dancing, drinking and fighting, funerals and weddings

The patterns of ritual are defined by Eyman and Duncan as visual motifs, but can also be considered thematic in content as well. For example, eating, whilst obviously visual, also underpins the twin themes of communal bonding and the importance of family.

A close look at Ford’s Westerns reveals a number of visual motifs that Eyman and Duncan do not mention, such as low angle action shots, and Ford’s propensity to arrange figures of three within the frame. These triptych tableaux, awash with religious symbolism, can be found in numerous Ford films, including those outside the Western form. The authors also do not include that most Fordian of visual motifs, the characteristic imagery of riders on the horizon, silhouetted against the sky. Figures are also continually shown almost overwhelmed by the surrounding landscape, as if consumed by the very habitat they either occupy or wish to conquer. If one incorporates Eyman and Duncan’s catalogue of visual motifs, plus some of the other examples previously mentioned, then a definitive list of these visual patterns can consequently be compiled as follows:

- Figures in triptych

- Low angle action shots

- Figures silhouetted against the skyline

- Wilderness and landscape as character

- Doors and fences

- Characters framed in a doorway

On occasion, Ford also adopts an expressionist approach to the mise-en-scène, notably in films such as The Informer (1935), The Fugitive (1947), and The Long Voyage Home (1940), the latter photographed in collaboration with the innovative cinematographer Gregg Toland. Although not used consistently enough by Ford to warrant inclusion in a list of frequently utilised visual motifs, it does highlight Ford’s willingness to experiment with visual style when the opportunity presents itself.

It becomes obvious from a close look at early Ford films that the director was already exploring his own style and aesthetic within the mise-en-scène, his use of muted and natural lighting in particular embellishing the image with shaded meaning and sub-text. Tom Paulus points out how the low-key shading in Bucking Broadway suggests the ‘heroine’s mood of terror and depression in the presence of the villain’ (Paulus, 2007, p.132). Paulus also maintains that Ford and his cameramen, Ben Reynolds and John Brown, were employing source lighting to imbue the image with a natural look some time before ‘effects’ lighting had become a common staple of Hollywood films (Paulus, 2007, p.132). This experimentation in the use of such lighting methods suggests a director unwilling to be constrained by the rigid rules and discipline of early film language imposed upon filmmakers of the time, whilst at the same time introducing the question as to whether or not the cameramen were as much ‘authors’ of these lighting techniques as Ford himself. All of the aforementioned thematic and visual motifs eventually coalesce into a recognisable directorial aesthetic, pointing towards the conclusive existence of a tangible approach to filmmaking specific to Ford, or, to return to Silver’s phrase, the ‘Fordian sensibility’.

In summary, whilst this thesis is first and foremost an auteurist study of Ford’s silent directing career, it critically explores the nature and definition of cinematic ‘authorship’ through this close study of Ford’s early work. As such, it recognises the traditional concept of director as auteur whilst not ignoring the complexities that arise from the biographical, social, cultural, technological, and institutional influences that shape Ford’s vision and approach. The thesis draws upon Wollen’s notion of the presence of opposites and antimonies in the director’s work, and Foucault’s idea of the director as a construct separate from the filmmaker as an individual, at the same time taking into account the role that journalism and marketing played in promoting Ford as Fordian. It should be noted that it will restrict itself specifically to Foucault’s hypothesis on the nature of the author-function only, a notion that is particularly applicable to certain aspects of the auteur theory. The thesis also incorporates Sarris’ contention that auteurism implicitly defines the director as the main author of his or her own oeuvre, and as such is a legitimate method for studying film and film history. There is also an acknowledgement that authorship is a complex combination of a network of influences ranging from aspects of personal vision, the discourses that surround the author in question, and the prevailing biographical, social, cultural and technological factors of the time. The question of authorship is deemed to be an ongoing dialogue and debate, with the thesis referencing various approaches from different points in the evolution of the auteur theory.

This work also identifies the development of the ‘Fordian sensibility’ through Ford’s earliest work, and a close study of primary film texts – some of which have never been examined before – and critically explores the concept of cinematic authorship. It does not attempt to question that Ford is an auteur, but it does examine what authorship means within the context of working in the Hollywood studio system between the years 1917 through to 1930. It also examines the early evolution of the ‘Fordian sensibility’ and how the creation of a personal directorial style such as Ford’s is shaped within a commercial and industrialised collaborative medium.